Joanna Rakoff’s My Salinger Year

What is it about being in your early twenties that makes the world seem so overwhelmingly crowded and yet so desperately lonely all at once? There’s something bewitching about it, too, and melancholy.

What is it about being in your early twenties that makes the world seem so overwhelmingly crowded and yet so desperately lonely all at once? There’s something bewitching about it, too, and melancholy.

On the very first page of her most famous and autobiographical novel, The Lover, Marguerite Duras seems to capture in one line the most powerful aspect of the book: “Very early in my life, it was too late.”

How can one adequately capture experiences that very often undo language itself, that are often so profoundly isolating precisely because they defy our common speech, our tested vocabularies and definitions of human experience? How do we find the right words to map that place?

Having grown up feeling starved for complex female antiheroes in fiction, women I could actually fully relate to without having to overhaul my personality, morality, or entire appearance, the recent influx of interesting, complex female characters in popular culture has been revelatory.

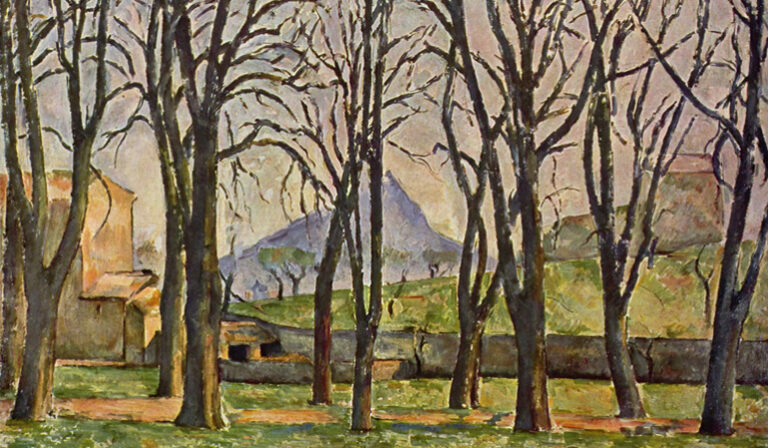

Learning from artists, how to write, to draw, to see, taught me of bounty. Their insistence, their calling, always, attention to the smallest things, taught me the most precious kind of survival: the abiding joy and knowledge that there is always something.

Adam Zagajewski’s “To Go to Lvov” is an elegy for a world, a family, a time, that will never return, but is chronicled with such fevered longing, such attentive encapsulation, that it somehow lives on.

When you start selling perfumes, you are in the business of selling stories. You must learn to be adept in all the tools a writer needs to do their work well. Scent is the most primal sense, the surest trigger of memory, of instinct.

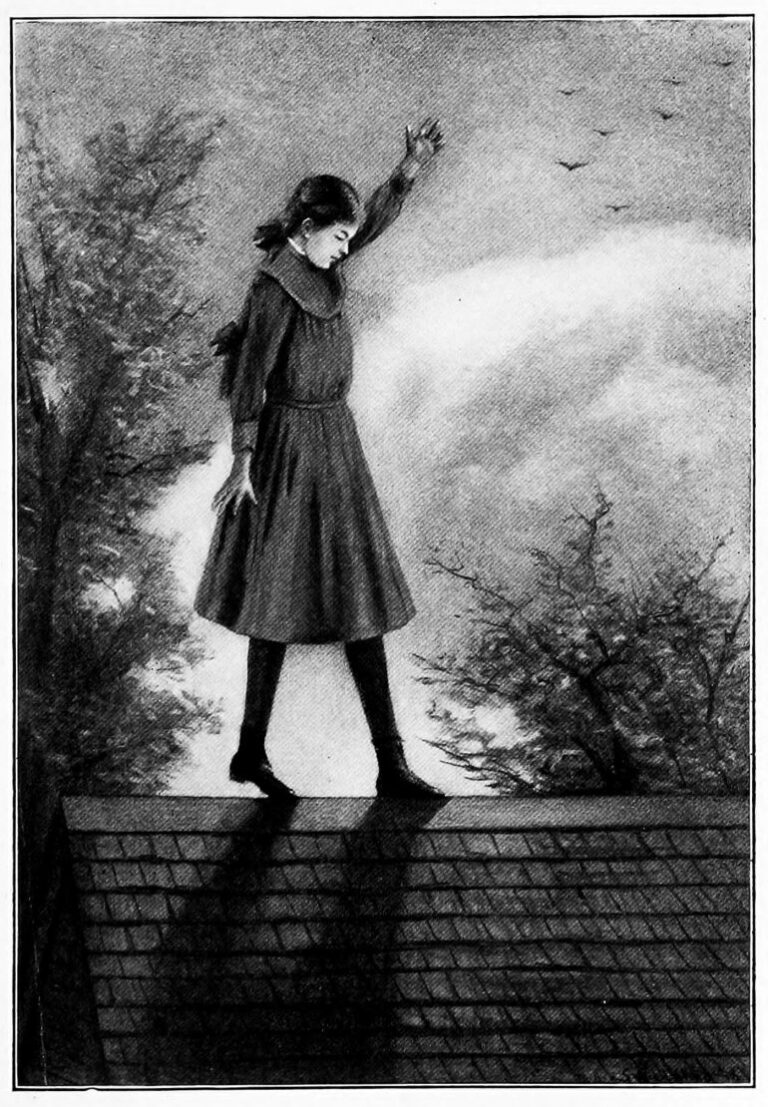

The ways in which Anne, the mercurial, earnest girl at the center of the story lived, learned, grew, and blundered her way through life resonated with me, a perennial outsider and dreamer, wounded by things that, like Anne’s cruel treatment at the hands of the Hammonds and the orphanage asylum, lurked in the corners of things—never forgotten, but making the joys of a safe refuge all the more poignant, warm, and vital.

If that reality was so vital to Nabokov, if its silenced heart is what makes the novel so haunting, then there is space, surely, surely, for the real, breathing girl to speak properly.

No products in the cart.