Being An Irish Story

“As naught gives way to aught,” Paul Muldoon starts his anaphoric poem “As.”

I think of this line when I’m searching—for a word, a piece of information, or a feeling. It’s a comfort: Muldoon begins from the point at which the void yields something.

I spend a lot of time searching. As a literary scholar working on women of the nineteenth-century, my subjects range from the understudied to the unheard of. The paper trails are paltry at best—a line in a city directory, a mark in a ship’s manifest, an advertisement in a newspaper, or a bill of sale. It’s what Saidiya Hartman has called “an asterisk in the grand narrative of history” as her archive of the Middle Passage runs murderous and thin over the Atlantic. It’s what Lisa Lowe describes as a “rhetorical ellipsis,” a willful silence, a colonial cover up where there are brutalities and affections not intended to be preserved. These grammatical place holders, the mismemories—the unlikely possibility of glimpsing sideways at a thing that will never come into full focus—have me pulling box after box from special collections, pumping sequence after keyword sequence into internet searches hoping to land on the right concatenation in our increasingly digitized world. Sometimes: it even works.

The pun Muldoon trades on is an old one and he knows it. He’s long been maligned for his difficulty, his rarefied knowledge, his expansive citational practice. But, as a poet, an ode writer to Joseph Mary Plunkett (who studied Gaelic in the Revival, Arabic, and Esperanto before he cosigned the Proclamation of the Irish Republic during the Easter Rising and was hanged for it), and Northern Irish himself, Muldoon is keenly aware, I suspect, that the inheritance of his homeland is at once a violent love and an abiding misgiving about his words.

When I ask about my great-grandmother, it’s my family’s words that muddy. And this, dear reader, is probably where my impulsive archival rummaging first begins.

Here’s what I know:

Mary McCrea was born sometime between 1886 and 1891. Her family (at least by the 1890’s) lived in an Irish Settlement, “the paddytown” northeast of Little Falls, New York, in the ancestral lands of the Haudenosaunee at the base of the forest that would soon become the Adirondack State Park. My best guess is that they were lured there, probably undocumented and overland by way of Canada, by the manual labor the Erie Canal promised. Herman Melville’s unhinged Captain Ahab rails to his crew in Moby-Dick (1851) that the villages of the canalway are “one continual stream of Venetianly corrupt and often lawless life. There’s your true Ashantee, gentlemen;” he extolls drawing on the parallels to African insurrection that Sterling Stuckey extrapolates, “there howl your pagans.” Mary’s father was not a “canawler,” but a woodsman who had occasional work at a nearby saw mill. When Mary was aged 2, her mother died in childbirth. And this is where our words get complicated.

The distance from aught to naught is a misdivision—an etymological slippage from Old to Middle English, and probably Latin before that. It’s a move from something (a thing owed; a possession; anything-whatever) to nothing (a trifle; nothingness; the number zero): an-aught to a-naught.

Mary’s eldest daughter and her namesake, my grandmother, was well into her 70s by the time I began asking about her mother. She would become inconsolably sad at these interrogatories—unable to speak, sometimes reduced to tears. “She had a hard life,” she would say, “and was so good. I should have been kinder to her.” My grandmother, I should say in a way that is trite and I suppose granddaughters are often predisposed to, was the kindest person I have known. It was her youngest sister, my great-aunt, that finally clued me in. “She was put out,” she said of her mother, “to a family.” My uncle says “put into service,” and my mother, also Mary, who was very close to her grandmother, uses the vocabulary of “babysitting” to account for this period. From roughly aged 2 to aged 7, Mary McCrea was made to tend house and care for five children in a family that no one seems to know much about. After five years, this family abandoned her and left Mary alone in an empty house to starve.

In his 1998 Clarendon Lectures in English Literature given at Oxford, Muldoon coins the term, “narthecality” to describe a central tenet of the Irish experience. Taken from the term “narthex” which is the threshold or vestibule or porch of a church where penitents who will not be admitted to the principal shelters of worship stand. To Muldoon, it’s this liminal distance that creates the critical aesthetic of Irishness—one that is always necessarily cryptic and canted, seen at an angle, a cipher to more obvious meaning. Colm Tóibín joked recently about Mary Lavin’s short story, “Happiness.” “Being an Irish story,” he said, “it isn’t about happiness at all.”

The first piece of paper I have found that bears my great-grandmother’s name is a 1920 Census record. Mary McCrea “sent word” to her father from the abandoned house. He arrived after some weeks and returned her to the Irish Settlement, to the home of one of her mother’s relatives. As a teenager, she found work at a nearby shoe factory and had since moved to town. She married an itinerant laborer, a first generation Irish-American who had fought hard against the nativist labor blocks and found work at the local bicycle manufactory. They had four children. Here, she lists herself and her woodsman father as New York-born. Her mother, she says, is from Ireland (though she would change this to the anachronistic and revealing “Irish Free State” by the 1930 Census).

The document is a cul-de-sac, an inscrutable cipher. There’s no way—at least that I have yet found—to tell its truths from its glittering fictions, the secrets it keeps. If Mary McCrea was born in the United States, there is no record of it. Her family and others like them lived out of the bounds of citizenship—scorned from the gridded commerce of so-called civil society to the wilderness on its outskirts—adjacent, but always outside of town. The Irish Settlement has been taken back by nature, overgrown and collapsed by the weight of intervening history. The legacy of Mary McCrea’s indenture and abuse is a thing that can still be barely spoken in my family. And I’m not sure if it’s from lack of language or lack of want.

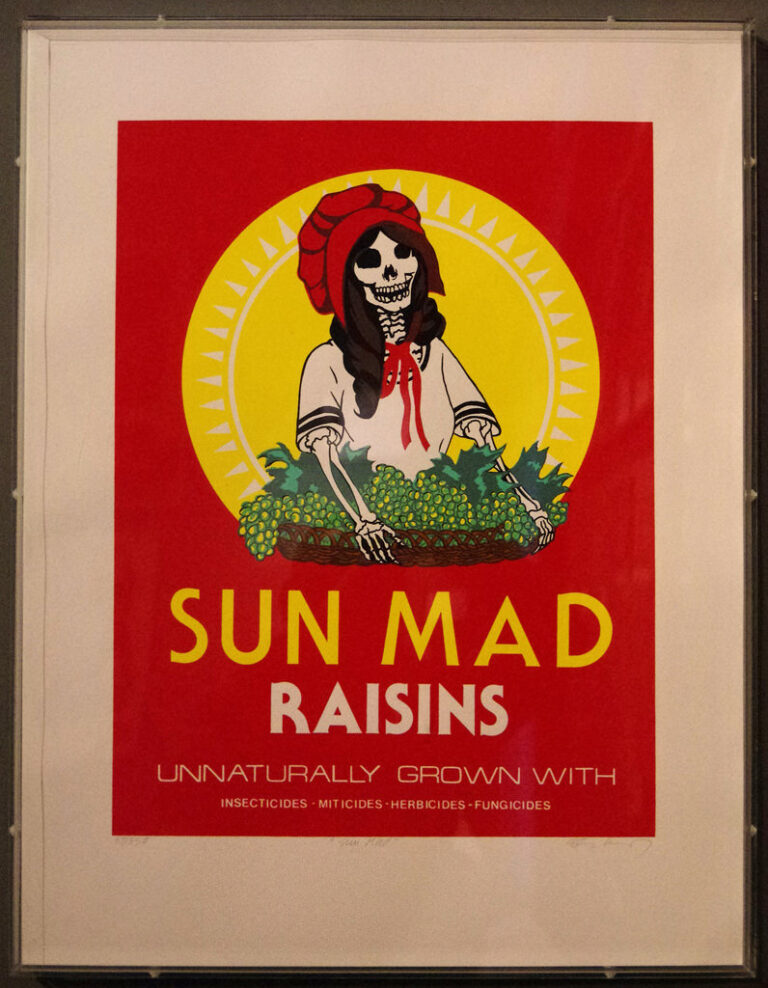

Within a generation Irish Americans became, if not wholly committed to, then at least, intentionally complicit in projects of white supremacy. If the problem of the twentieth century is, as W.E.B. DuBois wrote in 1903, “the problem of the color-line,” we can see the sons and daughters of Irish immigrants’ madcap scurry to put some distance between themselves and that edge. From the political machines of Boston, New York, and Chicago to the Moynihan Report to Steve Bannon, there’s a shame-faced shore-up of what is thought to be aught.

“I stood on the porch tonight— which way do we face / to talk to the dead?” Sharon Olds writes in “Birthday Poem for My Grandmother.” The narthex, I would answer, is located to the west of the nave. In an economy of dispossession, of suspicious naturalizations, of what Lowe speaks of as, “affirmation and forgetting,” someone is always left standing at the door.

“As” is a love poem, after all. It’s a sidelong devotion—all wordplay and switchbacks. Its essence is decocted from its original artifacts, once lost and now found, a reverse transit of its multiple parasitic meanings. It feels something like being in the archives, in a family, in love.

Muldoon crests his final stanza with a cipher, a secret calculation:

and the Roman IX gives way to the Arabic 9

and nine gives way, as ever, to zero

I give way to you.

Nothing, you see, could become anything at all. It could be everything.