Big Picture, Small Picture: Context for Jamaica Kincaid’s AT THE BOTTOM OF THE RIVER

This blog series, Big Picture, Small Picture, provides a contextual collage for a chosen piece of literature. The information here is culled from newspapers, newsreels, periodicals, and other primary sources from the date of the text’s original publication.

“And then there was no more Empire all of a sudden.

Its victories were air, its dominions dirt”

-Derek Walcott, “The Lost Empire”

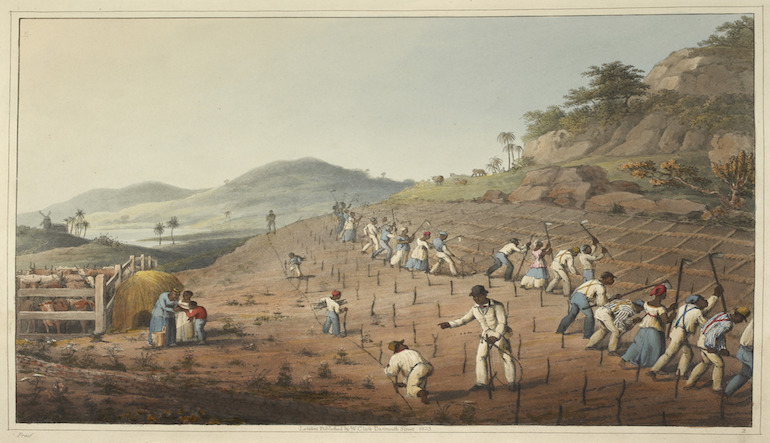

August 1st, 1834. At the stroke of midnight, church bells peal out across the island of Antigua, a 108-square-mile British colony in the West Indies. Thirty-two thousand newly emancipated slaves flood the lamplit streets, filling churches in every corner of the island with solemn prayer. They hope for a better future now that their long days of forced labor in the sugar fields are over. A reporter from the London Patriot details the scene for his British readers: “A more striking object of wonder and delight was the demeanor of the people . . . While every countenance beamed with happiness, there was no unbecoming excitement. Their joy was lively indeed, but it was calm and chastened.”

But two hundred years of oppression and exploitation do not evaporate overnight. A faction of former slaveholders and plantation owners vow to make “freedom” difficult for the suddenly self-reliant population, evicting those living on their land while refusing to offer living wages for those laborers seeking gainful employment. Over the next few weeks, the local government reinforces the status quo by giving favorable decisions to the rich white landowners. The same reporter from the Patriot weighs in: “An extensive and effective change in the Magistracy is absolutely necessary to protect the new freemen against the overbearing and unrelenting spirit of those who have been accustomed to deal only with slaves.”

As the decades roll on and slavery is abolished in the United States as well, tourism replaces sugar as Antigua’s leading industry. “The islands of the Caribbean, once primarily winter resorts, have become a year-round proposition for vacationists who crave a few weeks of loafing, fun and sun-tan,” the New York Times travel section advises in May of 1949. “Late word from the isles of flying fish and waving palms is that there will be no relaxing of tourist hospitality during the summer.”

Indeed, on the southern tip of the island, a new resort is being built with cottage houses and a private beach. Week by week, more plans are made for similar resorts along the white sands of the coastline.

Meanwhile, in the capital city of St. John’s, a baby girl is born to a poor family. Elaine Potter Richardson grows into a tall and awkward girl who struggles to fit in with her peers, but her mother teaches her to read at a young age and she takes solace in the city library. As a teenager, she clashes often with her mother, and shortly after her seventeenth birthday, she leaves Antigua behind to work as an au pair in Scarsdale, New York.

Living in New York City in her twenties, she ignores letters from home and reinvents herself. She declares herself a writer and changes her name. In the summer of 1978, Jamaica Kincaid’s first short story, “Girl,” is published in The New Yorker. Over the next few years, Kincaid will publish several stories in the magazine, including “The Letter from Home” in the spring of 1981.

In November of that year, the peal of church bells once again signals independence on Antigua, but this time the nation itself celebrates its autonomy from British rule. “Calypso music crackled until dawn Sunday, then gave way to the solemnity of special prayers in churches throughout this Caribbean island,” reports an article in the Associated Press. “Independence came at the stroke of midnight, when the Union Jack was lowered and Antigua’s yellow-blue-white-red-and-black flag unfurled before a capacity crowd of 25,000 at a cricket grounds. Fireworks burst overhead and warships from Britain, the U.S., and Venezuela fired salutes.”

Two years later, Kincaid’s debut book, At the Bottom of the River, is published to immediate acclaim in December of 1983. The thin volume weaves surreal narratives of post-colonial island life, complicated female relationships, and the pervasive longing for self-actualization.

Just two years into its independence, Antigua still feels the grip of international influences. The island nation sees 35 percent more American tourists this year than last, and the same week that At the Bottom of the River debuts, a cache of Soviet arms are found on a small islet off the coast of Antigua.

A few years later, Kincaid returns to Antigua and writes about her experience. In A Small Place, she imagines arriving on the island as a tourist from America, or Europe: “That water—have you ever seen anything like it? Oh, what beauty! Oh, what beauty!”

But Kincaid sees the island from a different perspective, through the eyes of the colonized. When she walks the old streets, named after British seaman, she feels the echoes of slavery. Passing by the private beaches belonging to the posh resorts where she wasn’t allowed to play as a child, she feels the ethnocentrism inherent in such a place. Resentment stirs within her:

What I see is the millions of people, of whom I am just one, made orphans: no motherland, no fatherland, no gods, no mounds of earth for holy ground, no excess of love […] and worst and most painful of all, no tongue. (For isn’t it odd that the only language I have in which to speak of this crime is the language of the criminal who committed the crime?)

The New York Times praises Kincaid’s “passion and conviction” and her “musical sense of language,” but other critics deride her embittered tone.

In response, Kincaid simply asks a question: “Do you ever try to understand why people like me cannot get over the past, cannot forgive and cannot forget?”