Big Picture, Small Picture: Context for James Baldwin’s “Sonny’s Blues”

This blog series, Big Picture, Small Picture, provides a contextual collage for a chosen piece of literature. The information here is culled from newspapers, newsreels, periodicals, and other primary sources from the date of the text’s original publication.

Am I blue?

Am I blue?

Ain’t these tears in my eyes telling you?

—“Am I Blue,” written by Harry Akst and Grant Clarke

Summer, 1957. A big band jazz concert on the Central Park mall in Manhattan is disrupted by gusts of heavy wind, toppling over music stands and scattering pages of sheet music into the air. Park attendants scurry around the stage in a vain attempt to collect the music, and even audience members leap to their feet to snatch wayward pages. Meanwhile, the musicians play on, forced into spontaneous improvisations of standard compositions.

That same week, swing trumpet legend Louis Armstrong celebrates his fifty-seventh birthday at the Newport Jazz Festival, playing a rollicking, ensemble-heavy set alongside old-time giants like stride pianist Bobby Henderson and Ella Fitzgerald. The concert is a throwback to the early days of jazz, but young musicians like pianist Sonny Clark are currently filling the clubs of New York with a new sound: hard bop.

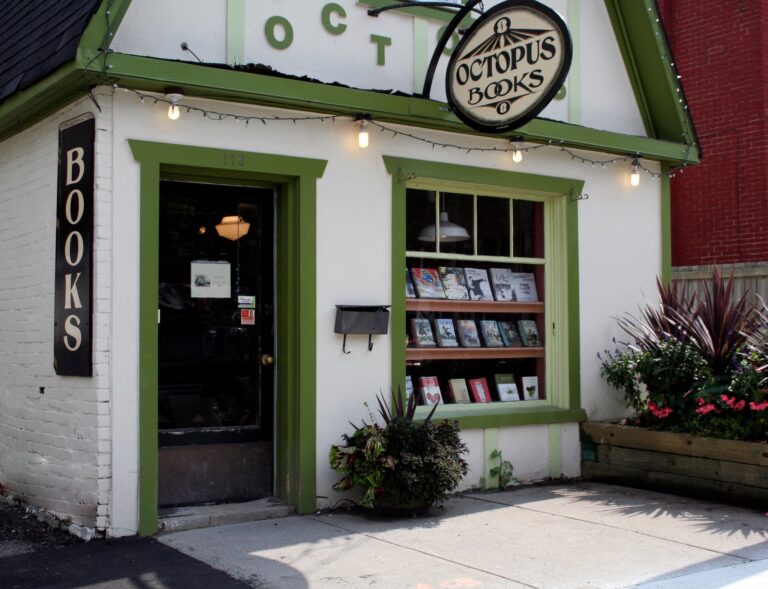

That month, in a studio in Hackensack, New Jersey, the twenty-six-year-old Clark records his breakthrough album Dial “S” For Sonny, released by Blue Note Records. On the track “Shoutin’ On a Riff,” Clark’s piano is driving and insistent, and on “Sonny’s Mood,” his playing turns bluesy and reflective. The album marks the arrival of a promising young talent, but Clark is already in the throes of drug addiction.

James Baldwin’s short story, “Sonny’s Blues,” is published that month in the New York City literature magazine, Partisan Review. The story’s narrator is a high school teacher from Harlem struggling to reconcile his relationship with his younger brother, Sonny, a jazz pianist hooked on heroin. (Despite the shared name, there is no evidence that Baldwin based his character on Clark.) When the narrator compares Sonny’s music to Louis Armstrong, Sonny responds angrily that he doesn’t play “that old-time, down home crap”; he’s into the virtuosic improv of Charlie “Bird” Parker.

The narrator recognizes the root of Sonny’s anger; his students, like Sonny before them, grow up “with a rush” until their heads bump against “the low ceiling of their actual possibilities.” The black youth are stifled by the oppressive system, trapped, and “filled with rage.”

In June of 1957, Mrs. Mae Mallory sues the city of New York over its school zonings. In the lawsuit, Mallory claims that her twelve-year-old daughter, Patricia, will not have the opportunity to thrive in the all-black Harlem high school she has been placed in because the facilities at Public School 88 are “substandard and in a hazardous condition,” and that P.S. 88 lacks a “well oriented and executed curriculum,” as well as an “experienced and trained teaching staff.”

Mrs. Mallory is right; in an attempt to improve the quality of schools in the Harlem neighborhoods, Board of Education officials ask for volunteers among the forty thousand New York City teachers to transfer to the so-called difficult schools for the following year. Only twenty-five teachers step forward, leaving 1,175 necessary spots still vacant. The associate superintendent of the school district surmises that the only option left is to “assign teachers without asking them.”

In “Sonny’s Blues,” the narrator and Sonny take a taxi through Harlem and reflect on the “killing streets” of the neighborhood they grew up in: “These streets hadn’t changed, though housing projects jutted up out of them now like rocks in the middle of a boiling sea . . . boys exactly like the boys we once had been found themselves smothering in these houses, came down into the streets for light and air and found themselves encircled by disaster. Some escaped the trap, most didn’t.”

Sonny tries to explain to his brother his own trap of anger, fear, and addiction: “It’s terrible sometimes, inside . . . you walk these streets, black and funky and cold, and there’s not really a living ass to talk to, and there’s nothing shaking, and there’s no way of getting it out—that storm inside.” He assures his brother that he’s clean from heroin now, but the longing to escape “can come again.”

Back at the Newport Jazz Festival, a panel discussion ponders the problem of narcotics in the jazz scene. One of the reasons for this connection, the panel finds, is that jazz has not been a socially accepted musical genre. Young musicians must learn the craft not in classrooms but in nightclubs and gin mills. Another problem, members of the panel claim, is the idolization of the lifestyle of figures like Bird, who struggled with heroin addiction and died at the age of thirty-four just two years earlier.

Since Dial “S” for Sonny in 1957, Sonny Clark plays on twenty-nine sessions for Blue Note and accompanies some of the biggest names in jazz, including Dexter Gordon, John Coltrane, and Grant Green. Clark’s tasteful compositions and liquid chops earn him a reputation as the quintessential hard bop pianist. On January 12, 1963, Clark plays a gig at Junior’s Bar in Manhattan. The next night he dies of a heart attack caused by a heroin overdose at the age of thirty-one.

In the final scene of Baldwin’s story, the narrator takes up Sonny’s invitation to watch him play at a small club in downtown Manhattan. There, he finally understands that despite Sonny’s addiction, despite his self-destructive tendencies, this club is Sonny’s kingdom, and his younger brother’s “veins bore royal blood.” He watches, transfixed, as Sonny and the band come together to find new ways of expressing the blues, the madness and beauty and sorrow of life: “For, while the tale of how we suffer, and how we are delighted, and how we may triumph is never new, it always must be heard. There isn’t any other tale to tell, it’s the only light we’ve got in all this darkness.”