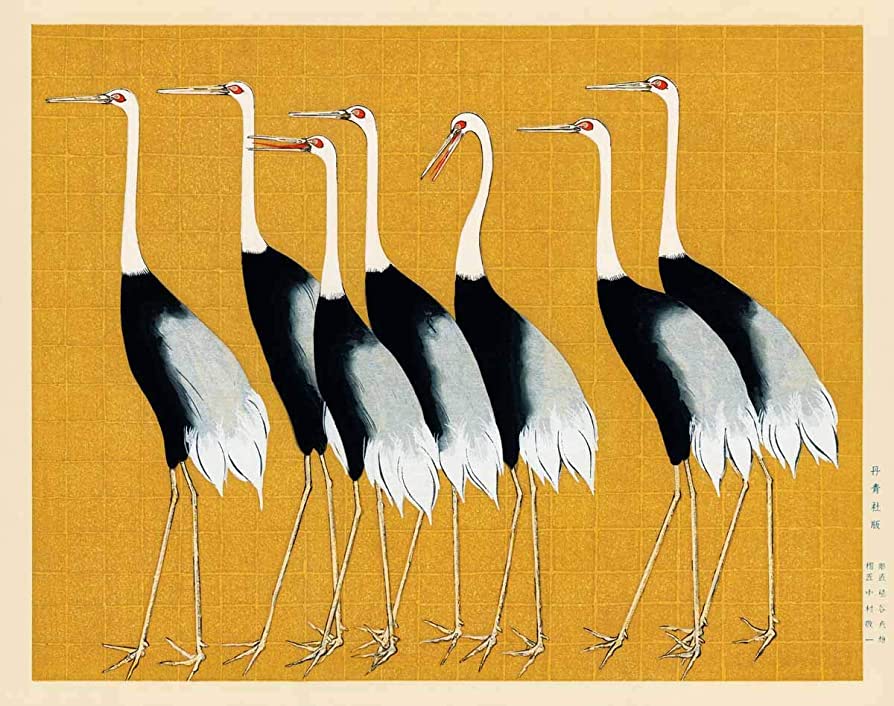

Birds as Metaphor in Birds of Maine and Big Questions

When it comes to teenagers, Ginni and her friends are pretty typical. They love watching boys, they’re embarrassed by their parents, and they think it’d be cool to start a band (though truthfully, none of them really have any interest in music or practice). Ginni’s crush is an albatross named James. She likes him for his extremely impressive wingspan, and you can often find her sitting in a nearby tree with her friends Ramil and Ivy watching James gracefully fly over the water. At night, Ginni likes to leave James small food offerings near his nest from her family’s share of the universal worm, occasionally making hyperbolic declarations of love to him out of earshot. “I want him to peck out my eyes. He’s so handsome,” she swoons.

That’s just what life is like for teenage birds living on the moon. Or at least, that’s what life is like for the teenage birds living on the moon in Michael DeForge’s latest comic, Birds of Maine (2022). The book, which is a collection of DeForge’s webcomic of the same name, might at first seem like a simplistic—albeit humorous—imagining of bird life, but it quickly turns into something much deeper. DeForge’s birds are not your typical avian brethren but rather a complex and sophisticated ornithological unit that have taken up residence on the moon after fleeing the Earth and its population of corrupt humans. DeForge renders them and their world in a style that feels like Charley Harper’s geometric birds have been dropped into a Wassily Kandinsky landscape, and the narrative reads like a futuristic tale reminiscent of Olga Ravn’s The Employees (2020) or Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy. In short, these birds are on another level. Still, there is something remarkably familiar about them.

The thing that’s so striking about the birds in Birds of Maine is just how human-like they are. They visit sculpture gardens, get exhausted caring for their young, go out to bars, play sports, experience traffic jams. And sure, their internet is bizarrely made from a complex connection of fungal spores instead of high-tech fiberoptics, but it is still the internet, persuasive and highly integrated into their everyday lives. They are just as self-conscious and preoccupied as the rest of us.

In fact, DeForge’s birds are reminiscent of a group of birds in another comic, Anders Nilsen’s Big Questions (2011). Like DeForge’s, Nilsen’s birds are brainy—if also slightly more philosophical—and they, too, inhabit a nondescript wasteland that seems entirely cut off from the rest of the human world. When a military pilot crash lands near their home, Nilsen’s birds mistake his plane for a larger bird and the bomb it was carrying for an unhatched egg. As they set about trying to decide what is to be done about the situation, they touch on difficult topics like death, the afterlife, and the mercy of the human spirit. The questions Nilsen asks his birds (and his readers) to think about are big, so it’s curious that he would choose birds and not humans as his main subject matter. But like DeForge, the two artists seem to find something inherently humane in the avian world, relying on the quirks of the animal to help guide them in illuminating what’s vital about being human.

Society has a complex relationship with birds. Tippi Hedren didn’t help make a good name for them when she allowed herself to be terrorized by a flock on screen in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 film, The Birds. I’ve met people so afraid of sparrows and pigeons and the like that they freeze up in complete terror at the mere sight of one. Usually the fear has to do with a bird’s ability to fly and the fact that they have access to certain areas of the world that we can only ever really dream about. Sure, technology might allow us to experience flight, but somehow, a bird’s ability to fly is directly tied to their mystery and, for some, their ominousness. There is something all-knowing about birds that seems to elevate them above humanity’s ability to understand things. Owls are wise, and it is the canary brought sacrificially into the coal mine that will succumb to the danger before everyone else. Because of their all-knowing image, they have become the perfect harbingers to deliver humanity with a potent dose of self-reflection, which is exactly what both DeForge and Nilsen set out to do.

DeForge’s birds left Earth long ago, and from the stories they tell each other, humans all but destroyed everything good about their home planet. Ginni, a teenage cardinal, makes fun of humans’ insistence on referring to things as being inside and outside of nature preserves. “What’s outside the nature preserve? ‘Not-nature?’” she asks. When an astronaut is sent by humanity to visit the birds on the moon, they crash-land in such a spectacularly embarrassing fashion that they can only spend their time pleading for both medical assistance and the preservation of their dignity. Eventually, the astronaut perishes and is slowly sucked into the birds’ environment. They become part of the internet, but their presence throughout the various networks is treated, ironically, like a virus—or as the birds say, “a rot.” Clearly there is no place for humanity on this particular moon.

The presence of humans in Big Questions also looms large and clumsy. After crashing his plane, the pilot wanders the wasteland trying to figure out how to get out of his situation while a mute man leaves his home after he discovers that his mother has died, and interacts with the birds for the first time. Both men are polar opposites of one another, reflecting humanity’s ability for salvation but also cruelty. In the end, the mute man is able to gain the trust of the birds, while the pilot perishes after being bitten by a venomous snake. The pilot, a man who can be viewed as trying to join the birds in his own form of artificial flight, turns out to be the farthest removed from the natural world. Just like the astronaut in Birds of Maine, there is no place for him amongst the birds of this world. He is too human and therefore likely to corrupt all that is good.

And there is a lot that is good about the moon in Birds of Maine. Here, families are chosen instead of biological, and a bird’s life is theirs to do with as they wish. The universal worm—which is quite literally a large worm growth—is responsible for making sure no bird on the moon ever goes hungry. Capitalism is scoffed at amongst the lunar birds. They view economics as outdated science that borders on the occult. When one of the birds reveals to her parents that she is interested in studying the field, her mother tells her, “Wanting to become an expert in economics is akin to…wanting to become a connoisseur of…of serial killing.” Humanity’s insistence on valuing capitalism over everything else is seen by the birds as their complete and total downfall.

And somehow, because it is birds that are telling us what we, most likely, already know about the state of humanity today, the information feels both delightfully funny and somehow extremely accurate, as if no better messenger exists to deliver the news to us that we, the human race, are headed towards disaster. Perhaps this has something to do with a bird’s aforementioned ability to elevate themselves above everything and everyone, giving them the upper hand (wing?) in identifying the crux of the world’s problems. But perhaps it’s also because both Nilsen and DeForge infuse their birds with just enough human spirit to make their stories feel relatable. No matter how avian the birds in Birds of Maine are, they still encapsulate a specific type of twenty-first-century wokeness that helps distinguish them from their real life counterparts (Nilsen’s birds are a bit less internet savvy since Big Questions was published in 2011), as well as push them into another realm of relatability where they are able to comfortably critique the thing that they are also very much a part of.

The final panels of Birds of Maine find Ginni sitting amongst her friends and family looking out into space. She tells them she’s “hoping for an unidentified flying object” right before the book ends. Her capacity to wonder is still largely intact. Big Questions ends with the birds choosing to take in and care for the mute man as if he is one of their own before a quick series of panels depicts two birds in conversation, with one eventually declaring that “you should live each day like it’s your last.” What DeForge and Nilsen have managed to do in both of their works is highlight some of humanity’s best traits and reflect them back to us through the use of those flighty, flittering creatures. Life is beautiful, they seem to be pleading. If only you would take a moment to try looking at things from a different perspective.