Compassing the Truth: Language in the Historical Novel

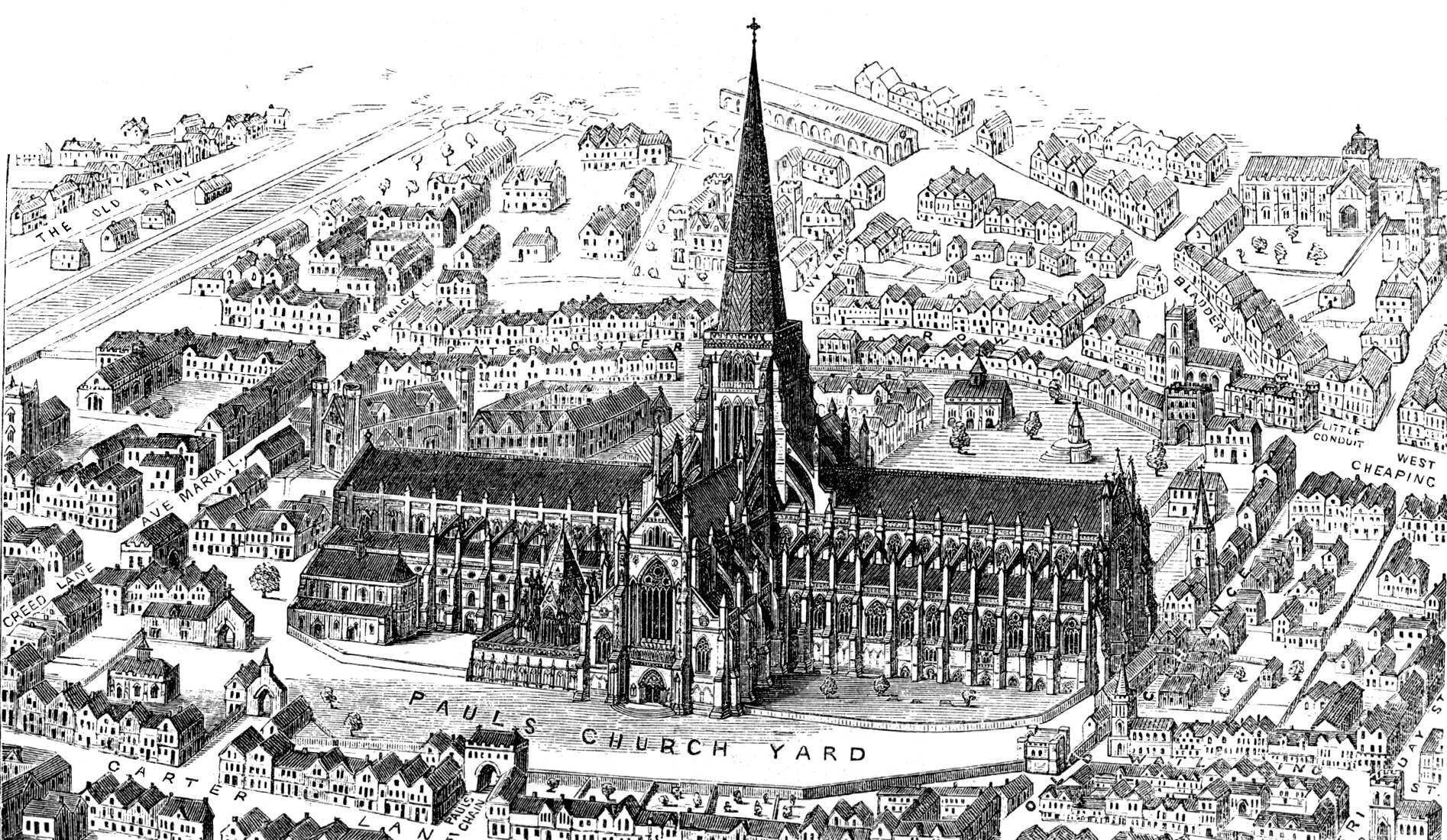

Writing a novel set in 17th Century London, I wrestle regularly with understanding my characters’ world. Have I done a good enough job comprehending their relationship to time? To daylight and darkness, to religion and mortality? I worry about getting the physical details of daily life right in the story I’m trying to tell…and then I worry that if I focus too much on the details, I’ll kill the narrative.

But of all the challenges, the greatest hurdle is language.

At first, I went at the problem of 17th Century language literally. I was a zealot for the authentic phrase–and authenticity was the beginning and end of what I aimed for. Knowing that I needed to find a way to keep 17th Century language ringing in my mind, I tried to start every writing day by reading aloud from Robert Burton’s The Anatomy of Melancholy or looking over something by Aphra Behn or Margaret Cavendish. Every morning, too, I’d stop in at this website, which tracks Samuel Pepys’ decade-long diary day by day. (If that sounds dry, then you haven’t read Samuel. Some days he just reports hours of eye-straining paperwork, the details of his meals, and his efforts to keep up with the Jones’ silver plate. Other days, between reports of political intrigue, he’s delightedly detailing his philandering, which he disguises by referring to it in French or Spanish–“I did ce que je voudrais avec her most freely”.)

Pepys’ language is a trove of delicious phrases. The singer “sings very meanly”…Pepys “falls to discourse” with his friends on a vexing subject, about which he later “did beat my brains all the afternoon”. He refers to malcontented and underpaid sailors as “men not to be governed”. Reading his daily diary entries, I happily gathered words. Jerkin, placket, medicinals, physick. Tansey, posset, cook maid. Ferandin (a type of cheap fabric), ribands (ribbons). Poxy, of course, and doxy (prostitute). People might besmear, church, gird, or bed one another. Books were bound, then clasped and bossed.

At some point, though, I began to feel uneasy about all this authenticity. How often, after all, had my writing students presented me with scenes overloaded with irrelevant material…explaining proudly that these things they were describing actually happened? And how often had I said to them, as gently as I could, Just because it happened doesn’t mean it fits in this scene. Reality is no excuse. Wasn’t I, out of reverence for History-with-a-capital-H, falling into the same trap?

Authenticity, I began to feel, was an essential goal, but also an insufficient one. If I wrote a novel in which characters spoke the way people actually spoke in the 17th century, it would lack fluidity—it would all but creak with self-consciousness. No one—myself include—would want to read it.

Thank goodness for David Mitchell, who summed up my problem and solved it in one word: Bygone-ese. This, from an interview Mitchell gave with Goodreads:

“…If you get [the dialogue in historical fiction] too right, it sounds like a pastiche comedy—people are saying “thou” and “prithee” and “gadzooks,” which they did say, but to an early 21st-century audience, it’s laughable, even though it’s accurate. So you have to design a kind of “bygone-ese”—it’s modern enough for readers not to stumble over it, but it’s not so modern that the reader kind of thinks this could be out of House or Friends or something made for TV—puff! Again, the illusion is gone.”

Bygone-ese: a one-word permission slip to temper my obsession with authenticity and remember that this is also art. And that the point isn’t necessarily to write 100% authentically historical language, but to gesture toward it in a way that feels compelling.

And that’s where the process gets fun.

In “A Wilderness Station”, one of Alice Munro’s characters refers to being unwell due to “an attack of the gravel and a rheumatism of the stomach worse than any misery that ever fell upon me before.” Reading that phrase, I’m standing right there next to this character in 1852. I haven’t a clue what an attack of the gravel is, or how much research Munro had to do to find that phrase…all I know is that the phrase is worth whatever mountain she had to climb for it. The words are a passport to another time and reality. Munro doesn’t have to furnish every room for us, or remind us that her characters are wearing 19th Century clothing and eating 19th Century food and walking 19th Century walks. All we need is that attack of the gravel and our imaginations supply the rest.

The best writers of historical fiction understand just how much authenticity the reader needs. In Hilary Mantel’s Wolf Hall, the characters sing part-songs and sleep in truckle-beds…characters “play at football” and wonder “under what persuasion” someone has made a certain choice. Mantel offers enough 17th Century detail and phrasing so we’re rooted in time—yet she tells her story in prose that doesn’t need to shout 17th Century at every turn. Likewise, in Year of Wonders, Geraldine Brooks uses words like “cozened” (tricked) and “spavined” (decrepit)…yet these words are sprinkled judiciously amid less dated language. Reading her work, I’m aware that she’s making choices to allow the prose to feel lucid to a modern reader—yet there’s never an anachronism, there’s never anything to break the 17th-Century illusion…and when the characters speak (“I keep a cow now, a boon that I was not in purse to have [in earlier days]”)—we certainly know we’re not in Kansas anymore.

Asked once to describe his approach to composition, Mark Twain used the image of a writer ceaselessly sorting and selecting bricks to build “the eventual edifice which we call our style.”

On with the picking and choosing, then. The word “countenance” used as a verb? Yes. And “compass”, too…when “compass” is used as a verb, then I feel my feet solidly on 17th Century ground. Also in the ‘yes’ category are phrases I found in Liza Picard’s Restoration London: when hens make holy water (i.e. never)…his tongue runs on pattens… snug’s the word… look you there now. In Jonathon Green’s Cassell’s Dictionary of Slang I found more jewels: He can’t find his arse with two hands, and the ever-so-subtle Kiss my parliament! (It means what it sounds like it means.) And then there’s one of my favorite Pepys sentences, which I love for its simplicity: Thence home.

In my own personal ‘no’ category: words that, even if authentic, have been overused in thinly-written historical films and books: macaroon, slattern, knave…and definitely, definitely whoreson.

I mislike that.

Somewhere along the way, too, I realized that I have a bone to pick with the serpentine sentences of the 17th Century. I just plain don’t like them. Sacrilegious, I know. But it sometimes seems to me that a great deal of the 17th Century prose that survives is the literature of ingratiation—letters by hopeful courtiers, or by brilliant thinkers currying favor with wealthy patrons. These sentences bend, wind, bow and scrape. Here, for example, is Descartes, writing to Princess Elisabeth of Bohemia, in a letter dated 21 May 1643. He tells her he’s sorry he missed her when he visited her court–but then again, he reasons, it’s probably better that he did miss her…for last time he saw her he was too ravished by her beauty to properly hear her thoughts on philosophy: “In such wise was I rendered less capable of responding to Your Highness—who undoubtedly already noticed this flaw in me—when I previously had the honor of speaking to her; and it is your clemency that has wished to compensate for that flaw by placing the traces of your thoughts upon paper, where, rereading them several times, and accustoming myself to consider them, I am indeed less dazzled, yet have only so much the more admiration for them, recognizing that they do not seem ingenious merely at first sight, but proportionately more judicious and solid the further one examines them.”

Et tu, René?

Since the main character of my novel is a woman, I’ve cast about plenty for a 17th Century woman writer whose voice rings right. Yet many of the women’s voices I’ve found are freighted with a similar sort of self-effacing, disclaimer-and-subclause-laden style that makes one read and re-read a sentence for meaning. I’m convinced that if I tried writing a novel in this sort of winding syntax, I’d jump off a bridge before I was half finished. My character, I realized at some point, would just have to be the one quirky 17th Century woman who speaks her mind with no fanfare. Since she learns English in the course of the novel (she’s a Sephardic Jew from Amsterdam, so would have been raised on Portuguese, Ladino, Castilian, and Dutch), it seemed natural enough that she might speak differently than many of her peers. So differently, in fact, that at one point a young man, appalled by her failure to play the coquette, chastises her for speaking a strange and rude English, with pronouncements brutal short.

There you go. As a friend in marketing likes to say: It’s not a defect. It’s a feature.

The process of choosing stylistic bricks continues to be a happy obsession. Where’s the sweet spot between authenticity and clarity? Should one include phrases that sound old, but aren’t, like to find out where the barley grows—actually a 20th Century phrase for coming to one’s senses? (Nope. I’m still too much a stickler for accuracy.) What about phrases that are, indeed, old…yet sound modern? (Reading Lawrence Norfolk’s rich Lempriere’s Dictionary, I thought I’d stumbled on an anachronism in the phrase ‘train of thought’ for a 17th Century character….but when I looked it up, I saw Norfolk was right—the phrase far pre-dates locomotives.)

These days the walls of my writing room are full of post-its with 17th century phrases—each a favorite, whether or not it ever makes its way into this novel I’m writing. Bit by bit, I’m working my way toward the language in which I hope to tell my character’s story.

Or maybe I’ve got that backward. Maybe, in selecting the bricks to build this novel’s language, I’m shaping the sort of story I can tell.

In its current form, my novel opens with a deathbed confession penned by my main character (yes, she’d call it ‘penning’, even when using a quill). The date is June 8, 1691—by the Hebrew calendar 11 Sivan, 5451. Her confession begins with a brief passage, the final line of which reads, “Let these pages compass the truth, though none read them.”

Compass, used as a verb, means encompass, and also comprehend. After years of holding a secret, this woman is at last permitting herself to tell the truth.

Yet compass also means plot, skillfully devise, contrive by craft…and she knows that her words not only embrace the truth she’s telling, but irrevocably shape it.

Building a language to compass a truth….the notion makes sense to me whichever meaning of the word I use. I’m still working out how the bricks fit together, but the labor is a delight.