“Dear Lucky One”: The Westing Game Invites Us to Play

Thirty-five years after the publication of Ellen Raskin’s novel The Westing Game, readers still rave about it. As one literary agent tweeted recently, “if I could find the new Ellen Raskin, I would be the happiest agent ever.” Bestselling novelist Gillian Flynn ventures that in Gone Girl, she maybe, “finally,” achieved the wordplay of The Westing Game, which she reads “probably once a year.”

Mention The Westing Game to full-grown adults, and we explode with adulation. We don’t just like the book—we “love, love, love” it. We’ve named kittens after the characters. We recall Turtle Wexler’s whip-like braid and Sam Westing’s whispering corpse and Judge J.J. (Josie-Jo) Ford’s endless frustrations. We remember learning that even from the very first sentence, things may not be what they seem:

The sun sets in the west (just about everyone knows that), but Sunset Towers faced east. Strange!

Winner of the 1979 Newbery Medal, The Westing Game is ripe with the juiciest elements of storytelling: disguises, dares, notes, gossip, accusations, explosions, spies, a girl sleuth, a millionaire’s fortune, and two (presumably) dead bodies. Beneath these charms, however, brews something more consequential. Sure, we follow Sunset Towers’ new tenants—including five teenagers, a doorman, a doctor, a restauranteur, a judge, and a seamstress—to Samuel W. Westing’s mansion. We listen to a reading of the mysterious industrialist’s last will: a puzzle game of his invention, with clues and cash incentives. We watch the eight pairs of heirs theorize, scheme, and spy to solve the riddle of Westing’s death and inherit his estate.

But for Westing and his creator, Ellen Raskin, the goal of the game isn’t riches. It’s companionship—the lifelong loyalties formed among Westing’s heirs, who begin as strangers and become dearly connected.

Raskin also sought to connect with her readers—and with future writers. As a college student, she had no idea “where children’s books come from,” so she donated to her alma mater all of her Westing Game drafts. Part blind groping, part careful calculation, Raskin’s writing process offers strategies for developing our own work—almost like the rules to a game.

Rule #1: It’s Not What You Have, But What You Don’t Have That Counts

To solve the puzzle, Westing advises, “It’s not what you have, it’s what you don’t have that counts.” By design, each pair starts with almost nothing—just a few words printed on scraps of Westing-brand paper towels—and they get nowhere until they put all the pieces together.

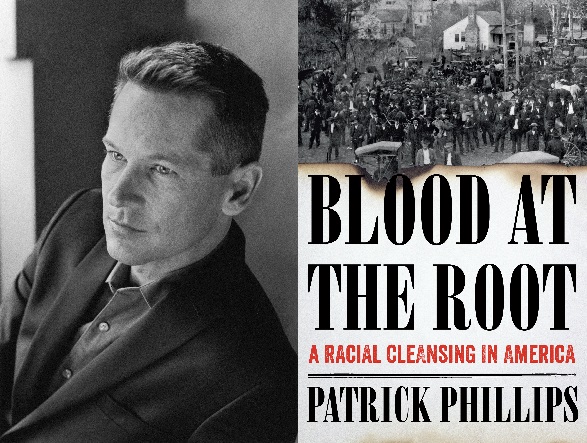

When Raskin began writing the novel in 1976, she, too, had random scraps. A fan had asked her to write “a puzzle-mystery.” It was the year of the U.S. bicentennial, and so into Sunset Towers she placed a mythically American “melting pot of people.” It was also the year that eccentric millionaire Howard Hughes died and his will was dramatically contested.

What Raskin didn’t have was an outline. In fact, she despised them: “It’s just deadly to have to write according to an outline, and know what’s going to happen. You have to give your characters the freedom to tell you what’s going to happen next, to grow and interact with one another.” The writing process took two years and several drafts, but all the unknowns allowed Raskin great flexibility as she worked.

Rule #2: Follow The Notes

Without an outline, Raskin looked to a book on musical improvisation, which offered guidelines we can use:

- Sit at the keyboard

- Choose a scale

- Choose a rhythm

- Start playing

It’s a point worth repeating: this intricate novel—sixteen point-of-view characters! a nineteen-part will!—developed through improvisation. Raskin “chose a locale and a time, and just by doing so, it started going on its own.” When an editor’s note expressed confusion over a named “Berti,” Raskin renamed her “Crow,” and marveled at the character’s newfound dark severity. Revising other names—real-estate agent “Harry Heartland” to “Barney Northrup,” the doorman “Murph” to “Sandy McSouthers”—opened surprising new directions for the puzzle.

Rule #3: Reinvent Yourself

In the course of playing the Westing game, characters develop new identities: shallow wives become savvy entrepreneurs; shin-kicking teens become Chairmen of the Board. Sam Westing’s obituary tells a classic tale of American reinvention, from immigrant child to “Paper King” with a penchant for disguises—including Ben Franklin, Betsy Ross, and, well, ahem, others.

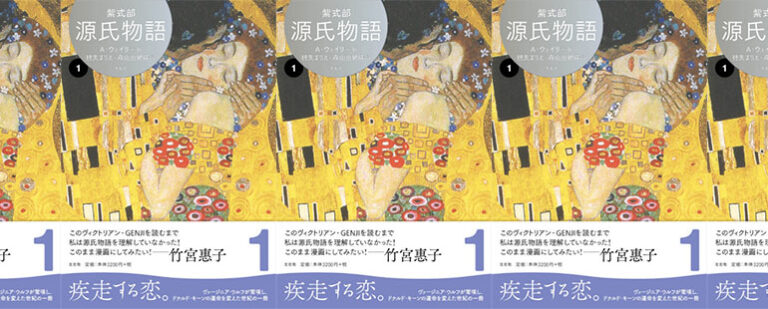

Raskin herself entered children’s literature as an illustrator. She designed the jackets for over a thousand books (including the 1963 cover for A Wrinkle in Time), before reinventing herself as an author in 1970. Ultimately, she designed every aspect of The Westing Game, from cover, to typeface, to layout, to bulleted chapter dividers resembling bombs. (In fact, when a binder’s error trimmed the margins of the first printing too close, Raskin had 15,000 copies shredded because she’d measured the margins to “the length of an average eleven year old’s thumb, so that a child could easily hold a book open without covering up any type.”)

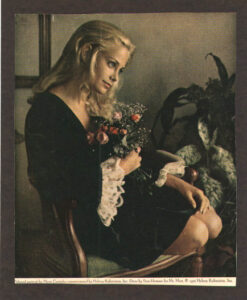

As an illustrator, Raskin collected 30 years worth of magazine pictures into her “Swipe File”—ten file cabinets of images. For her novel, she looked through her “People” files and selected two images that appealed to her, especially in contrast with one other. These images helped Raskin create the Wexler sisters: pushy, daring Turtle and dutiful, passive-aggressive Angela.

“All illustrators have a swipe file, but not many authors do,” Raskin said. What might develop in our work when random images collide? A modern spin condenses the bulk of Raskin’s filing cabinets: Serendip-0-Matic, a new site from the Center for History and New Media, generates pages of web images from any text. Type in something like “sisters siblings younger older” and see an inspiring assortment.

Rule #4: Look at the Entire Board

There are other benefits to writing like an illustrator. The Westing Game is scene-driven, full of present action and dialogue between the partners as they sort through information. (We never see Turtle Wexler at school, for example, or anyone engaged in a non-game pursuit.) Paragraphs are often under 150 words—what we Ploughshares bloggers know to be a reader-friendly length.

From the first draft, Raskin thought about story in design ways. On every other page, there’s a visual break: a row of bullets signaling a section’s end, or other kinds of texts— letters, clues, notes, parts of Westing’s will. Conceived to keep young readers interested, these alternate texts are some of the most entertaining parts of the novel. We can’t resist interpreting new information.

These “excerpts,” as Raskin called them, offer multiple means of characterization, as with this player’s note on another Westing heir:

OTIS JOSEPH AMBER, Age: 62. Delivery boy. Fourth-grade dropout. IQ: 50. Lives in the basement of Green’s Grocery. A bachelor. No living relatives. Westing Connection: Delivered letters from E.J. Plum, attorney, both times.

And this message posted in the Sunset Towers elevator by Judge J.J. Ford:

$25 REWARD for the return of a gold railroad watch inscribed: to Ezra Ford in appreciation for thirty years’ service to the Milwaukee Road.

And this headline from an old newspaper:

VIOLET WESTING TO MARRY SENATOR

With each excerpt, we also learn something new about its interpreters— their dreams, their histories, their irritations. An illustrator’s strategy to engage the eye develops narrative content. It also reminds us of the reader’s needs, even in the early-drafting stages.

Rule #5: Find Teammates

Would we adore a book that simply lets us solve a puzzle? No. What we “love, love, love” about The Westing Game is uncovering the mysteries of its “eight imperfect pairs of heirs” (the novel’s original title), and watching their lives enmesh years after the game ends. Similarly, Raskin’s relationships with her editors illustrate why artists should receive as well as give.

For example, Raskin began authoring her own books because of editor Ann Durell, who suggested the then-illustrator write about her childhood during the Great Depression. The story became Raskin’s first novel, The Mysterious Disappearance of Leon (I Mean Noel). (Fun fact: Raskin even cut Durell’s hair—they’d talk about manuscripts as Raskin played barber.)

Whereas Raskin drafted novels “as an illustrator writing”—with too much attention to physical details—Durell sped up the pace. “Kids find real-estate details boring, I think,” Durell noted, nudging Raskin to focus on character. Not surprisingly, Item #16 in the will—Westing’s true objective for each heir (“To Denton Deere: his first patient. To Chris Theodorakis: hope”)—never made it to the final manuscript. It’s too weighty a card to play in a game so delicately balanced.

Like Samuel W. Westing, Raskin’s legacy is one of generosity. She wrote with an objective we might all keep in mind: “a book is a package, a gift package, a surprise package—within the wrappings is a whole new world and beyond.”

The art of writing is, in essence, an act of giving. And The Westing Game continues to ignite sparks of recognition in readers and writers, kids and grown-ups. In its glow, we are—all of us—Lucky Ones.