Denise Levertov’s Politics and Poetics

More often than not, Denise Levertov claimed she was not whichever appellation had come to her doorstep: not a mystic, not political, not a “woman writer,” not an authority. Her objections have more to do, I think, with the consequences of public identity—being read as an identity, rather than for one’s work—than her actual political orientation, which was a lifelong commitment to poetry as but one form of protest.

The humanism which grounds Levertov’s poetry also precludes, in her case, more focused partisanships beyond universalist principles, like denuclearization. But the immersion required for such deep consideration, and the immersion she details in her famous essay “Some Notes on Organic Form,” countervails her later aversion to political identification: if “form is never more than a revelation of content,” form itself is a humanizing strategy against otherwise reductive thought. Levertov herself later termed her work a “poetics of engagement,” and in her essay “The Ideas in Things,” inveighed against poetry that prizes strictly intellectual thought, “rather than perceiving concrete images as the very incarnation of thought.” Such use of incarnation (italics hers) suggests a poetics composed not only of artistic intention, but spiritual and political embodiment. There is something sacred to thought embodied in a poem, and that, for Levertov, is a subtle incorporation of a politics, too.

While Levertov is considered a major twentieth-century poet, her work languishes now in a special kind of literary stasis of being taught, but not necessarily championed or even referenced, by contemporary poets outside the classroom. Her work is raised in moments of acute political crisis, but wider interest does not persist much beyond them. She may well be privately loved, as I learned when I mentioned to my friend I’d be writing about her—neither of us knew of the other’s affinity for her. And for many she is a gateway poet; whether reading her leads to discovery of the Objectivists (the more interesting track) or in other directions is unclear. No doubt there are some complications: her clarion anti-war work of witness mingles in occasionally objectionable characterizations. The figures of ancient Rome and barbarians—as in the personal “Ways of Conquest” and the political “Three Meditations”—are called up as analogies for unexamined motifs of imperial power. She tends to read disability as tragic. Such issues can be in part credited to the problems inherent to poetry of witness at large—a literary mode whose practitioners sometimes neglect to consider how their view necessarily affects different communities differently. But the preservation of her own innocence is not Levertov’s priority, nor is rehabilitating her without acknowledging these issues mine.

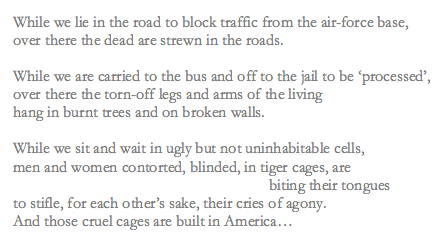

Levertov made persuasive use of acknowledgement in her poetry against the Vietnam and Gulf Wars. Though this strategy now feels insufficient on its own, the opening stanzas of Levertov’s “The Distance” (1975), participates in such rhetoric as much as it enacts a critique of it:

The plaintive irony in the parallel, both literal and technical, images in the opening stanza strikes an uncomfortable equivalence that Levertov draws out in the non-progress of “While,” “While,” “While,” alternating between the frustrations of local protest and verbalizing distant violence, which is brought home again, like a punch to the gut with that further acknowledgement: “And those cruel cages are built in America.”

As John Balaban describes in his introduction to Audrey T. Rodgers’ Denise Levertov: The Poetry of Engagement, to use the lyric to consider public matters, rather than private confessions, was considered by most critics of her time to be out-of-bounds: “a poem written about the war in Vietnam could only be polemic—probably sincere and right-minded, but almost certainly marred by shrill yapping from the soapbox.” Meanwhile, Levertov was notoriously critiqued by Robert Duncan for too mainstream a sensibility and milieu; George Oppen likewise told her she was not political enough.

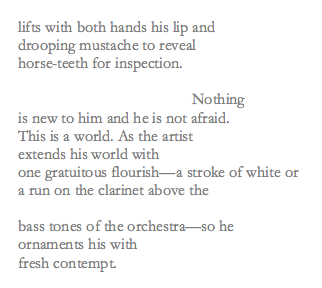

In fact, Levertov had long been writing socially conscious poems, which often go unnoticed in comparison with her more forthright political work. Her witnessing eye was not only haunted by international atrocity—in an early poem, “The Grace-Note,” from her 1961 collection The Jacob’s Ladder, registers a hostilely policed domestic environment, yoking together resistance and artistry in the figure of “Adam Misery,” who, in a morning’s “Sabbath quiet” on an empty industrial street, is coolly defiant while “the cop frisks him,” as he

Adam Misery is unfazed, with bared teeth (and presumed tongue) echoed by the last stanza’s orchestra, with its “run on the clarinet,” producing the grace-note of resistance to a policed state—of the many, one here is singled out: “This is a world.” His protest, likened to artistry, is pitched by the title in a tone of “grace,” singing out his righteous contempt. Such a lyric scene suggests the power of poetry’s work in witness. In Poetry, Narrative, History (1990), Frank Kermode attests: “good poems about historical crises speak a different language from historical record and historical myth…[t]hey make history strange and they are very private in their handling of the public themes. They can protect us from the familiar; they stand apart from opinion; they are a form of knowledge. Quite simply they are better poems than the myths provide, and much harder to interpret.”

Levertov’s idiom, at once hermetic and accessible, proceeds from her private “intuition of an order, a form beyond forms, in which forms partake, and of which man’s creative works are analogies, resemblances, natural allegories,” as she writes in “Some Notes on Organic Form.” But her own softening of protest by way of allegory has always struck an off-note with me, for there exists no allegory in her detailing of atrocity of warfare in Vietnam—she and Muriel Rukeyser, of the poets of their generation, actually travelled there together to see it. There is foremostly experience and its internalization, in an atmosphere of genuine political, profoundly human objection, to be found within her poems of moral appeal. One might wish for a journalist’s inclusion of detail for this subject, but Levertov never quite relinquished her sense of her own Orphic role to the documentary, as she later wrote: “I do not believe a violent imitation of the horrors of our times is the concern of poetry. Horrors are taken for granted. Disorder is ordinary. People in general take more and more ‘in their stride’—the hides grow thicker. I long for poems of an inner harmony in utter contrast to the chaos in which they exist. Insofar as poetry has a social function it is to awaken sleepers by other means than shock.”

And just how, the question follows, would poetry accomplish these “other means”? What we might find, if we extend our attention to Levertov again, is that increasingly sought-after merging of the political and the spiritual. Further, we might find an adaptable model for a poetry that inculcates in readers a familiarization with conversion. The daughter of a converted rabbi-turned-Anglican priest, Levertov herself underwent a religious conversion, late in life, to Catholicism. Over the course of her life’s work, it is not difficult to see the generative power that an openness to the space of conversion offers—an analytic objectivity, intuitive as it is grounded in observation, shapes her lyric inquiries as much as organic form itself. Such a record of the meditative lyric is itself a spectrum of contemplation and political conversion, a form of knowledge in the mutual languages of colloquy, protest, and prayer.