Detachment in Fiction from Fleur Jaeggy and Jean Genet

Fleur Jaeggy’s fiction works, two short novels and two short story collections, are marked with a quiet violence and a very particular brand of detachment. Importantly, though her characters operate through various calibres of neurosis, they do not experience their melancholy or habitual pain as opposites to a preferred, more buoyant state. The world they occupy, then, unfolds at a slight removal from our own: it is a place where alienation, dysfunction, and disappointment are unquestioned, non-negotiable terms.

These terms, which dictate their inner lives and exterior relationships alike, endure even in light of tragedy and violence. In the titular final story of the collection Last Vanities, the elderly Verena Kuster witnesses her husband jump to his death from a window in their home. Later, she reflects, ‘To push one’s husband out of the window, using no more than words, persuasion, is a form of spirituality.’ Bereaved, it is not grief that takes hold of her but a devotional transformation: ‘She felt sure of the ways she held herself now, enjoyed a certain sensual pleasure… She had finally entered into her body.’

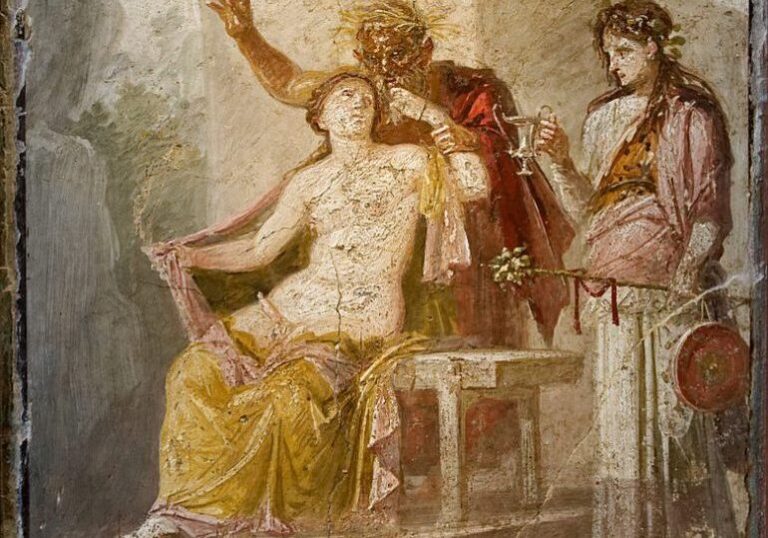

The reader quickly realizes that, much like in Jean Genet’s fiction, Jaeggy’s characters are out of joint with morality and its norms. Unfamiliar with empathy and compassion, their transgressions go unopposed by such counter ideals—indeed, as they’re entirely without recourse to an established set of values, the term ‘transgression’ doesn’t really apply. Similarly, though they experience the world from a position of ontological melancholy, it is a sadness unmarked by prior knowledge of glee or revelry. Detachment is the sole substance of their emotional lives, and so, they operate under an inversion of ideals again akin to Genet’s novels, wherein murder and theft become saintly, martyred acts. Their squamous sensibility is inherent; they are indifferent and cruel in the same way they are dark or fair, lissome or stout. If they are happy, they are ‘darkly happy… observing one’s own void.’

Markedly unlike Genet, however, is the recurrent depiction of flesh as a sterile conduit, as we see with the narrator of the novel SS Proleterka. An adolescent girl embarks on a cruise with her estranged father, the ship becoming the locus of what she intends to be a sexual awakening. However, long starved of emotional contact and inexperienced in compassion, she’s unable to identify their absence. Ultimately, the sex she has with the crew members doesn’t induce the empowered discovery of her erotic self; rather, it signals a failed attempt at agency: ‘Nikola shoves me violently into the cabin…. He is violent on the bunk too…. Nikola knew how to take my thoughts.’

Marked by a dysfunction indelible to her molecular makeup, these coarse terms of engagement are incapable of either demeaning or liberating her. She is not depicted as an aberrant deviant or a violated victim but simply as a person seeking a calibre of intimacy that, even if she were to attain it, she would be ill equipped to recognize or sustain. In “The Last of the Line” from the collection I Am the Brother of XX, we see a more extreme example in young Caspar, who is determined to ‘serve pain.’ He shows a wound on his temple to the game warden, who endeavors to protect Caspar from future harm, but the old man’s affection and concern are met with violent scorn:

‘You are preventing my brother from wounding me,’ Caspar said with rage. He lunged at the aging game warden… The old man fell and hit his head on the iron in the shape of a scythe used to scrape the soles of shoes.

Without the affective components necessary for apprehending tenderness, Caspar’s preternatural displacement endures. It is such relentless, matter-of-fact fatalism that makes reading Jaegyy’s prose feel like taking up a dare. Her characters unveil axioms that we, indoctrinated in ideals of sympathy and sanitized notions of selfhood, are too reactive or susceptible to acknowledge, let alone embrace. Shorn of reflection and clemency, their detachment makes way for a blunt freedom whose possibilities are both unnerving and tantalizing: ‘During the night the mother embraced her and called her by the name of one of her husbands, the one who wasn’t her father. The sheets were hot.’

Unschooled in taboo and so unafraid of what they might discover, they discover that memory is a phantom, intimacy a lie, and devotion a snare seeded with violence: ‘maybe,’ we read, ‘the cross itself will drive her to squeeze it till it bleeds like a pomegranate fruit.’ They demonstrate that morality, as a concept and a way of being, has been stretched too thin to serve everyone: these characters are those individuals just out of reach, continually untouched by such standards. In its place, they have fashioned a ‘pariahistic’ spirituality of anathema and dissidence, one which places them beyond benevolence, but also beyond reprehension:

If you want to know more about it then go ahead and become you yourself – her steady eyes are saying – become you yourself the victim.