Earing the Clink of Chisels: An Imperfect Love Letter to Reading Literary Magazines

Susie Anderson, an archivist at the Philadelphia Museum of Art Library & Archives, wheels out the metal cart on top of which sit a half dozen boxes of modernist “little magazines.” “Enjoy,” she says before leaving me to my own devices. My hands, suddenly clumsy, feel unworthy to un-velcro the clear plastic sleeves and pull out the March 1918 issue of The Little Review, which features the first serialized installment of Joyce’s Ulysses. The berry-red cover flakes under my fingers, delicate as a baked sheet of filo dough. “Making No Compromise with the Public Taste,” reads the journal’s byline. Inside: Joyce, Wyndham Lewis, Pound, and others. The cover’s dye has bled into the issue, freckling all the way through several pages to “Stately, plump Buck Mulligan…” I have come here to look, to view, the little magazine, to celebrate its thingness, its is-ness, to consider the impact and legacy of the publication, to experience a progenitor of the contemporary literary magazine, to see its pages, its type, its margins, its contents, but, as I tuck into the book object, I can’t help myself, I begin to do something I didn’t expect—I begin to read.

Before I walked into that room, before Susie even wheeled out the cart, I hadn’t expected to read the literary contents of these little magazines, and I’m not sure why. Every time I pause in front of a stack of lit mags at my house, I find myself flipping through one for a small bite, a morsel. Gimme something good. I find myself often re-reading things I’ve already read and feeling surprised by them again and again, as if the literary magazine keeps the poems new and Ziploc-fresh. This feeling never seems to run out for me, the poem never becomes a part of the book I have already read. The literary magazine is the cake I keep and eat too. So of course I re-read Joyce, so of course I re-read Stevens in the December 1918 issue.

What manner of building shall we build for

the adoration of beauty?

Let us design this chastel de chasteté,

De pensée . .

Never cease to deploy the structure . . .

Keep the laborers shouldering plinths . . .

Pass the whole of life earing the clink of the

chisels of the stone-cutters cutting the stones.

Removed from the oeuvre, the poem, like a lone Kahlo portrait, looks at one in the eyes, so to speak. This Stevens poem titled “Architecture for the Adoration of Beauty,” which appeared alongside his “Nuances of a Theme by Williams,” seems suddenly rooted in what rhetoricians call the kairotic moment, its timeliness, its tick upon the Stevens timeline. It becomes a part of the process, rather than the product, of Stevens’s craft.

As all periodicals do, the literary magazine likewise proctors a sense of its place as cultural capital and within the literary economy of its time period, and it no doubt characterizes its time period’s mores. (Just consider Stevens’s brazen colonialism, the founding of his ars poetica, his chastel de chasteté, upon laborers likely conjured from his white imagination of the builders of the Egyptian pyramids.) The Philadelphia Museum of Art’s copy of the December 1918 issue in which the two Stevens poems appear contains a handwritten inscription from an illegible signature to Marcel Duchamp, positioning the magazine, perhaps even its contents, inside the vector of notice of the Dadaist artist. Inside, we find editor Margaret Anderson’s “A Note to Our Readers,” which begins, “For over a year I have tried not to bore our subscribers with accounts of how difficult it has been for us to keep on publishing the Little Review,” send us all your money, tell your friends, do the right thing, thank you and goodnight. To know that Stevens, oblong stone in that great henge of modernism, published two poems in a literary magazine with financial sustainability problems affords me, a poet, some commiseratory satisfaction, a Polo to my lonely Marco cast back through time.

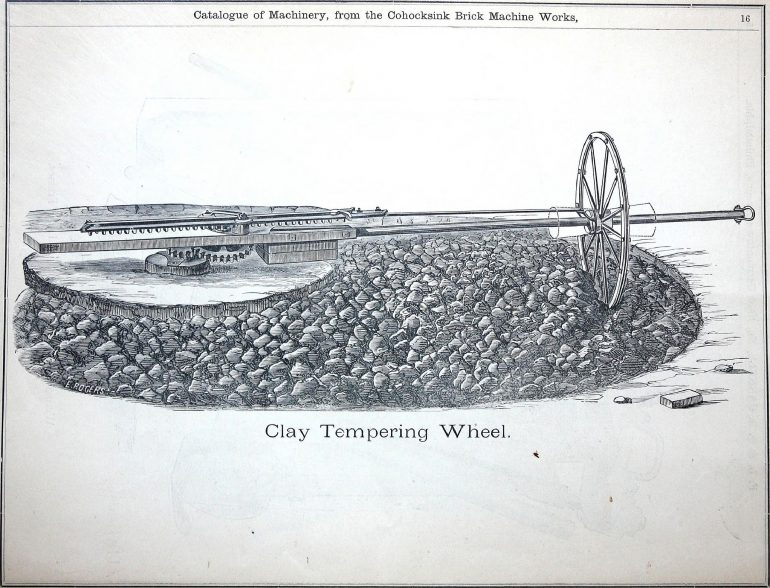

Reading poetry, contemporary or otherwise, in literary magazines often allows us insight into the writer’s process, how the raw clay of poems are cured between their initial publications into a brick in the wall of full-length collections. I often give students Vievee Francis’s poem “Say It, Say It Anyway You Can,” which first appeared as a prose poem in Rattle, and then, in her 2012 collection Horse in the Dark, as a lineated poem. As a reader, I understand something more about the poem’s cadence and the poet’s calculation when I see how a poem has changed from the literary magazine to the book. I see the rising dough and the baked bread at once. Every draft is both an elegy and a love letter to the previous draft, and there’s always ars poetica in the what’s-changed.

I can’t help but think about how our contemporary literary magazines will seal our moment’s poems and short stories and spellcasting away for some happened-upon reader. (“I think about you a lot, future person. // How you will need / all the books that were ever read / when the screens and wires go dumb,” Dana Levin writes.) Somehow, no matter how old or new the literary magazine, the writing inside always has a kind of canned-upon-picking sweetness, even if it seems dated, a victim of its time. It’s as if, upon reading a literary magazine, I have just arrived in a storm, just come in from the weather, my cheeks raw, not knowing if I’m yet warm.