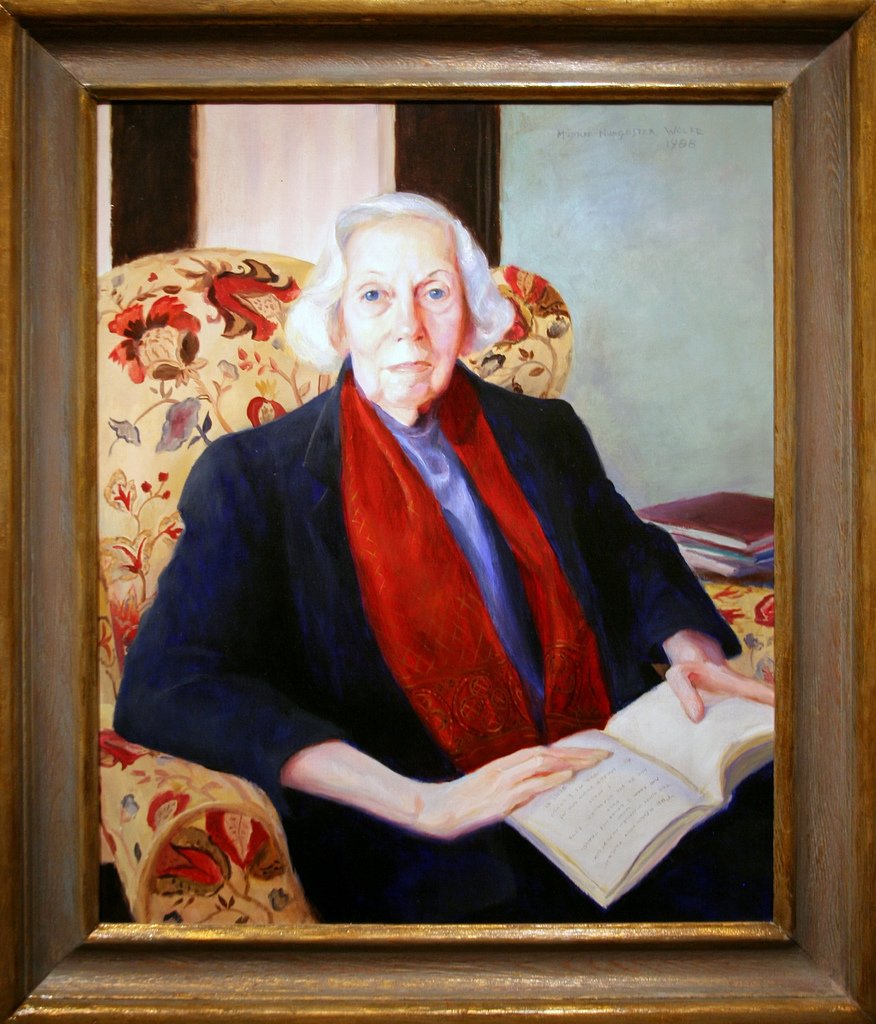

Empowerment can start in the kitchen: Eudora Welty’s DELTA WEDDING and THE OPTIMIST’S DAUGHTER

Before women were planning to march on Washington by the millions, our voices were contained in our own homes, gaining traction in quieter moments with family, when we could learn how to express our concerns, our creativity, and our love. Home is where we learned the various intricacies of being a human member of a human family. I learned this largely from my mother, grandmother, and aunt, while we stood in the kitchen rolling dough and stirring pots, listening to each other’s voices and telling stories over each other until dinner was ready.

This is what I find as well in the pages of one of my favorite writers, Eudora Welty, who raises domestic scenes to an art form. Two of Welty’s most memorable scenes take place in kitchens: an early scene in Delta Wedding, where an aunt and her motherless niece bake a cake, and the climax of her Pulitzer Prize winning novel The Optimist’s Daughter, where the protagonist confronts her stepmother over a breadboard that belonged to her mother. The kitchens of these two Welty novels are hubs of action like the kitchen of my childhood home, where private acts prepared me for the revolutions I inherited as a woman.

In the opening chapter of Eudora Welty’s Delta Wedding, Ellen Fairchild bakes great aunt Mashula’s cake with her nine-year-old niece, Laura. The cake recipe, passed down from antebellum Mississippi, is the through line to the scene, in which Ellen reflects on her daughter’s upcoming wedding. This cake has one grated coconut, fourteen guinea eggs, a splash of rosewater, the rind of a lemon, one grated nutmeg, and blanched almonds. As Ellen separates the eggs, she lets Laura grind almonds with a mortar and pestle, showing the tradition and attention involved in baking the cake. Welty moves seamlessly between Ellen’s thoughts and actions; adding the grated nutmeg and lemon rind, Ellen “diligently assumed [her family’s] happiness,” and separates eggs as she thinks of her hopes for her daughter’s wedding. She is the mastermind not only of the cake, but the whole house, family, and future. The kitchen is where Ellen can become not only a domestic artist, but the family historian, who passes the family recipe to the next generation by enlisting her niece’s help.

If a woman in a Welty kitchen can honor the long dead through their recipes, she can also expect to defend them through bakeware. Laurel McKelva, fresh from the death of her father in The Optimist’s Daughter, sees a breadboard in the kitchen as a symbol for the neglect of her mother’s memory during her stepmother’s reign over the house.

“What have you done to my mother’s breadboard?” she asks Fay, her father’s selfish young widow. “Look where the surface is splintered,” she says. “You might have gone at it with an icepick.”

Fay is obtuse and disrespectful, a stranger to this kitchen, an inheritance she does not deserve. “Who wants an everlasting breadboard? It’s the last thing on earth anybody needs!” she responds.

Importantly, Laurel’s dead husband made the breadboard for his mother-in-law, planning, grooving, and fitting it so she’d have a beautiful board worthy of her bread. When Fay says all bread tastes alike, Laurel tells her “you never tasted my mother’s.” The breadboard facilitated and framed Laurel’s mother’s artistry, an extension of the kitchen itself.

The breadboard, like the cake recipe, is a symbol of where the family has come from, and where it is headed. Laurel calls the breadboard “the whole solid past” and raises it over her head as though considering it a weapon with which to strike her father’s widow. Instead, says she can get along without it. “Memory,” Welty says on the final page, “lived not in initial possession but in the freed hands, pardoned and freed, and in the heart that can empty but fill again, in the patterns restored by dreams.” The heart refills with the comforting knowledge of ancestors and their rituals—small, housebound, works of care and love that sustain a family through generations, with or without keepsakes. For Welty’s women, the important memory is how to make the cake or the bread, the recipes inscribed with an almost spiritual resonance.

The kitchen, metaphorically the epicenter of work in a home, is seldom in the foreground in such key scenes, its domestic rituals often overshadowed by the world outside. By focusing on women in a kitchen, Welty seems to shrug the mantles that keep her marginalized—regional and gendered—subverting expectations for canonical American literature as public or inhabited by important men. Both Delta Wedding and The Optimist’s Daughter are fiction that elevate women’s work to emotional survival as well as physical. As a writer, Eudora Welty acts as an ethnographer for the minutiae of women’s daily work, writing the domestic world not as preludes to or background for the scene, but as the scene itself.

My mother and I deduced the cake recipe through reading this passage and made Great Aunt Mashula’s cake as an experiment. This eventually became my traditional birthday cake. This may not be one of the most noteworthy aspects of a life, but like for Welty’s characters, it is a shared act of creativity each year. We have modernized the recipe to make it our own; instead of fourteen guinea eggs, we use seven regular chicken eggs, for example. We buy nutmeg ready-grated. But the cake is still a time-consuming labor of love, one passed to us, too, by Great Aunt Mashula.

Most families have some version of Laurel McKelva’s mother’s breadboard as well—the talisman that serves as a reminder of survival of a family, an expression of celebration and love. Counting these private moments and everyday arts worthy of our time and reflection is already a radical act of redefinition, smaller than a million-woman march, but certainly a first step.

Image: Eudora Alice Welty (Mildred Nungester Wolfe, 1988)