Experiments in Perspective

A crucial lesson I learned early on in my attempts at writing fiction is that every character is you–and not you. Characters have parts of you inside of them because you wrote them. But they are still not you. Chris Abani once said in a workshop that readers will always wonder if your characters are you–even if your main character is a Chihuahua. There’s not much to do about this wondering except write the characters you want to write with complexity and empathy.

For each character that is not like yourself, you should be asking yourself this: if I were this character, if I had this upbringing and history, if I were in these circumstances, what would I think, feel, and do? Take the notion of “write what you know” and apply some big-time empathy to it. Of course, that doesn’t mean you have to make your characters “nice.” In a craft talk on this subject, and on the topic of likeable characters, Jodi Angel said, “We don’t go to the page to make friends. We go to see something other and apart from who we are.” The characters in her short story collection You Only Get Letters from Jail are written from the perspective of a teenage boy, and in this interview with Alan Heathcock, she elaborates:

when I start to think about a story, and I get a line or two forming in my head, I step immediately into a character and I hear that character’s voice, and that character oftentimes sees the world in a way that I don’t tend to notice. That character isn’t afraid to speak a certain kind of truth, and some people might define that certain kind of truth as dark, but one person’s darkness is another person’s light, and for many of my characters, they don’t know the difference. . . . the worst thing that I could ever do to them is force them to conform to something tidy and mundane and commonplace. To make these characters do nice things with nice people and have nice thoughts would mean that they would die on the page, and I like them too much to sentence them to that kind of gentle and acceptable death.

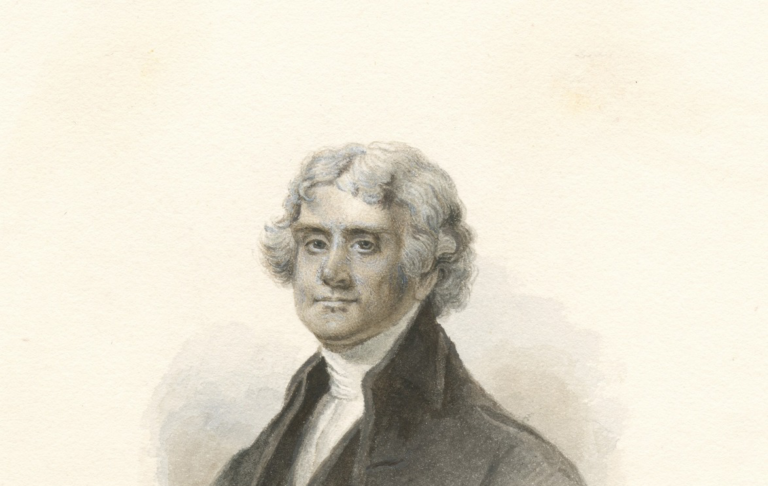

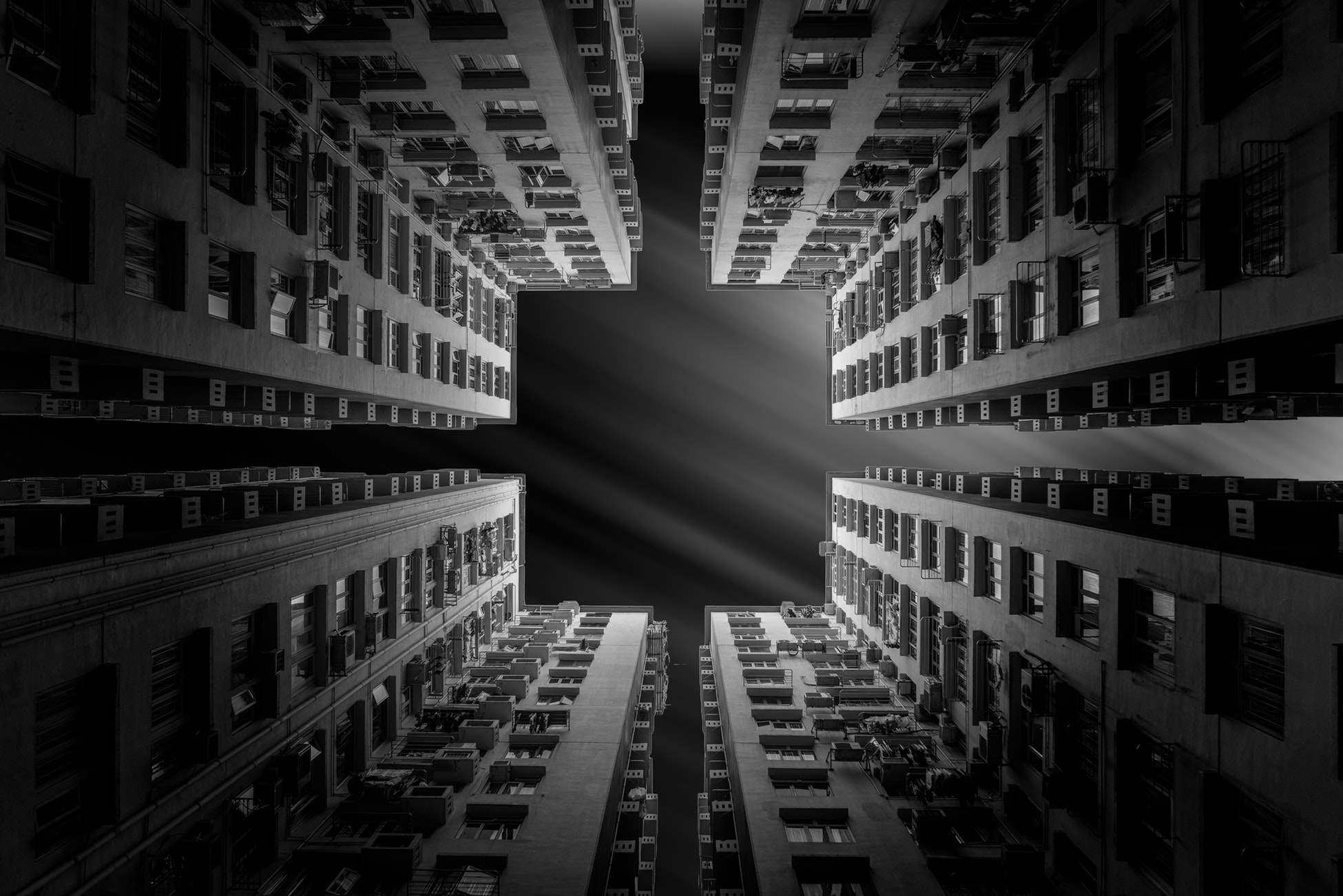

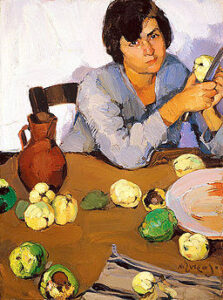

I like to use works of art in exercises experimenting with different perspectives because there’s something visual, something concrete to get the ball rolling. I’ve selected a few works here, but you could certainly do this exercise at a gallery or museum, where some choice overheard dialogue could give you additional perspectives to explore.

The Prompt

Envision three perspectives on one of these works of art. What would three different people think of this work? How might their thoughts on the art diverge from what they say about it? You could start with your own perspective as a warm up. If you have characters you are working with already, you could look at the piece from each of their perspectives. If you’re looking to do something new, here are some other possibilities. Write about that work of art from the perspective of:

- Someone half your age.

- Someone you knew when you were under the age of ten, someone you still think about as an adult.

- Someone ten to fifteen years older than you.

- A parent.

- A grandparent.

- A child lost in a museum.

- Someone who is about to ask for a divorce.

- Someone who is about to propose marriage.

- Someone who is starting to think they might be pregnant.

- Someone who took a road you did not travel. For example, I considered seriously but never pursued being a choreographer, an actress, an archaeologist, a costumed sales person at a toy store, a linguist. Students in my classes have written from the perspectives of art historians, anthropologists, and characters inside of the paintings themselves.

Bonus Prompts

Do you find any of the perspectives you’ve been mucking around in particularly compelling? Are any of the characters related to each other? How so? Do their different perspectives on the work of art constitute a framework or starting point for a short story?

Keith Ridgeway’s short story “Rothko Eggs,” originally published in Zoetrope: All-Story, is a coming of age story written from the perspective of a teenage girl and uses her thoughts on art, as well as those of her father’s and her boyfriend’s, to great effect. You might consider how a character’s changing interpretation of a work of art might present you with a story: what are the turning points in a person’s life that would do that? I tend to think in terms of fiction, but there’s certainly an idea for an essay or memoir in that question too.