Female Agency in Dystopian Novels

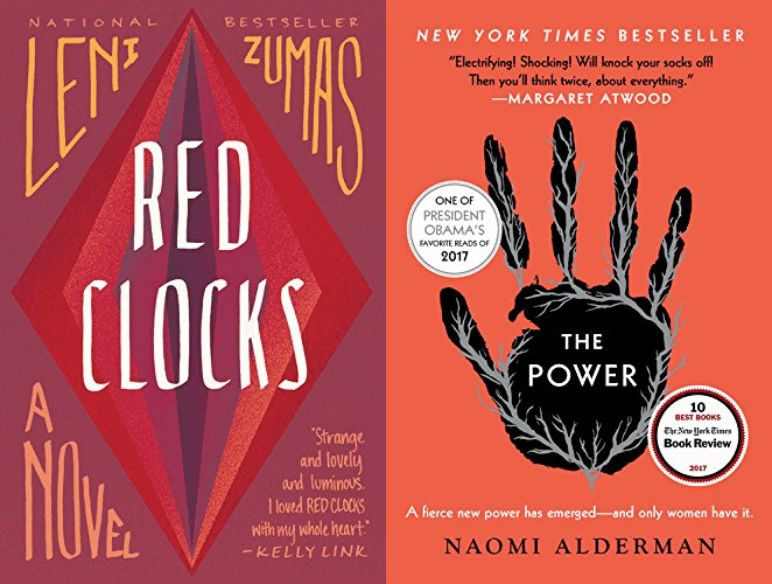

When Margaret Atwood introduced The Handmaid’s Tale in 1985, she called it an “antiprediction,” explaining: “If this future can be described in detail, maybe it won’t happen.” The last few years have seen a slew of laws and rulings restrict women’s sexual and reproductive rights in numerous states and anti-women measures and sentiments echoed in the highest offices of the federal government—developments that seem eerily reminiscent of the world Atwood described. Two recent novels, Red Clocks and The Power, build on the genre of The Handmaid’s Tale by reimagining the fate of female agency with the urgency of our time.

Leni Zumas’ Red Clocks, released in January 2018, presents a not-too-distant future in which the US has ratified a 28th Amendment on Personhood and enacted other measures outlawing abortion, calling for the death penalty for any abortion provider, restricting fertility treatments, and limiting adoption rights to couples. It weaves together the stories of four women affected by the new laws: a single teacher wanting to become a mother, a suburban mother disillusioned in her marriage, a teenager unexpectedly pregnant, and a forest-dwelling herbalist who offers her natural tinctures to women in trouble.

While the vision of these women’s new circumstances seems stark, Zumas makes clear how easily women’s rights can be diminished day by day amidst public complacency. The novel exemplifies what happens when what for years had been “a fringe idea, a farce,” becomes reality. “Tons of injustices happen in broad daylight,” says Mattie, the pregnant teen, “when ordinary citizens are aware but do nothing.”

The women in Red Clocks find ways to overcome their obstacles by working together, and alliances determine the fates of at least two of the main characters. But I found the actions of support from strangers—an anonymous tip that changes a courtroom outcome, a secret kept at all costs, medical services provided at great risk to help those in need—the most compelling aspect of Zumas’ narrative. Contrasted with the inaction of others throughout the story (not to mention the rivalries and betrayals among women that further undermined their chances to succeed), the book pushed me to ask myself how far I would go as an ally to fellow women in similar circumstances.

The story of a nineteenth century female polar explorer that the teacher is researching becomes another small thread in the narrative of Red Clocks. The lone voice of Eivør Mínervudottír from the far reach of the frozen Arctic of 150 years ago reminds us that a woman’s struggle to be heard and to be the author of her life is a long and ongoing one, connected to every other woman no matter the time or place. It is another way Zumas succeeds in framing the notion of female agency as both timeless and urgent.

Naomi Alderman examines female agency using a different framework in her 2016 novel, The Power. The premise is a bolder one: teen girls suddenly begin to develop a “skein,” a strip of striated muscle around their collarbones that allows them to deliver deadly electrical charges through their hands. The phenomenon at once threatens society’s gender norms and raises new questions of power—interpersonal, political, and even global.

At first, we see the positive impact the newfound power can have—in some instances it allows girls to escape from abuse and ensures their safety and freedom. It spreads to older generations of women who learn to activate this power themselves and gain advantages never before available to them. In the beginning, the role reversal taking place brings a new balance to gender dynamics that is easy to cheer. I found it especially interesting to view the specter of harassment and assault through flipped gender roles—parents telling their boys not to go out alone, not to stray too far—and to question the different reactions that this reversal brings to light.

As the story unfolds, however, we see the negative effects the power can yield. Men feeling threatened by it overreact and attempt to contain it through invasive tests on girls and women; some men go so far as to form underground terrorist groups to strike back. Individuals of both genders seek to take advantage and find a way to profit from the new power. And those on the fringes under these new norms—in the fluid place between genders—are accurately portrayed here as most vulnerable. Alderman reveals the double standards so ingrained in the way society deals with gender roles, as well as the risk and chaos likely to come with any disruption of norms.

There is a point in The Power when the pendulum swings to its opposite extreme, where female agency turns into retribution that goes too far. What had been a refrain for men’s application of their power—“because they can”—becomes the refrain for these female abusers too; it seems no gender is immune from the pitfalls witnessed today in the form of toxic masculinity. It is an interesting thought experiment that Alderman elaborated on in a New York Times interview:

“I hoped at least at the outset it would be good for women to feel or imagine what it would be like to be in a position of control. It’s always nice to have a little peek and see how society would look from the other side,” she said. “But finally, you have to ask, are women better than men? They’re not. People are people.”

The two very different approaches of Red Clocks and The Power join a chorus of women reimagining female agency. Given all that is at stake at this moment such writers’ voices, the questions they ask, and the warnings they sound are as important as ever.