Fiction Responding to Fiction: Charlotte Perkins Gilman and Doris Lessing

The Fiction Responding to Fiction series considers the influence that a short story has on another writer.

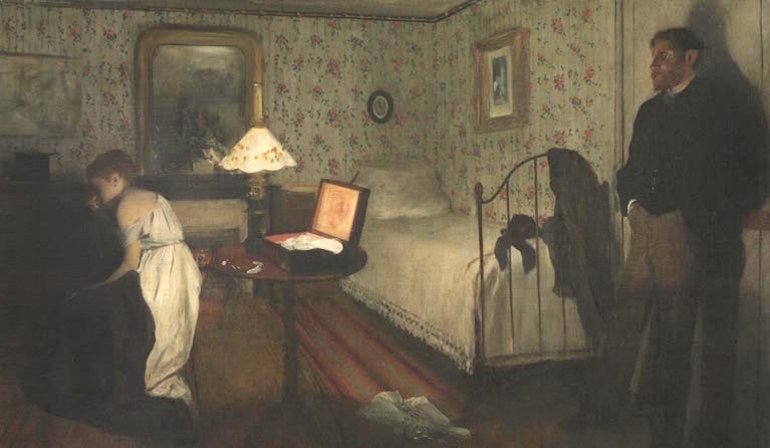

The iconic story “The Yellow Wallpaper” was published in 1892 by Charlotte Perkins Gilman and remains a staple of early feminist fiction. Written in the first person, from the point of view of a woman experiencing postpartum depression, the story was apparently sent by Gilman to the doctor who prescribed a “rest cure” for her depression. In 1983, Doris Lessing responded to Perkins Gilman’s classic story with “To Room Nineteen.” Included in the collection A Man and Two Women, Lessing’s story is considered one of her best short stories and also a classic feminist text. Although seventy years passed between the two stories, part of Lessing’s response to the original story is to point out how little had changed in the lives of women.

“The Yellow Wallpaper” takes advantage of its first-person narrator by allowing us to access her interiority. The story is confessional in nature; there are often asides that mention the actual writing of this document by the protagonist:

John is a physician, and perhaps—(I would not say it to a living soul, of course, but this is dead paper and a great relief to my mind—) perhaps that is one reason I do not get well faster.

The contrast of “a living soul” with “dead paper” sets up one of the central conflicts in the story, with the paper on which she is writing echoing and foreshadowing the wallpaper of the title.

As the story continues, the protagonist continues to talk about writing, especially as it connects to hiding her writing from her husband, John, and from her sister-in-law:

Such a dear girl as she is, and so careful of me! I must not let her find me writing.

She is a perfect and enthusiastic housekeeper, and hopes for no better profession. I verily believe she thinks it is the writing which made me sick!

Here, again, Gilman sets up a contrast: housekeeping, which is the preferred profession by society and family members, and writing, which is something that can cause illness and must be hidden from others.

The narrator’s final comment on writing is one that is perhaps familiar to every writer, then and now:

I don’t know why I should write this.

I don’t want to.

I don’t feel able.

And I know John would think it absurd. But I must say what I feel and think in some way—it is such a relief!

But the effort is getting to be greater than the relief.

Half the time now I am awfully lazy, and lie down ever so much.

From this point forward—at approximately the halfway mark in the story—the narrator no longer speaks of writing. Her attention turns completely to the wallpaper. She is searching for patterns and meaning in the wallpaper; no longer does writing hold her interest, no longer does she find solace or meaning there.

Lessing’s story takes place in London and its suburbs in the early 1960s. Rather than allowing the protagonist to be the narrator, Lessing utilizes an unnamed first-person narrator at the start: “This is a story, I suppose, about a failure of intelligence: the Rawlings’ marriage was grounded in intelligence.” The use of the clause “I suppose” both introduces us to the narrator and shows us how the narrator will be commenting on the story throughout. The narrator never returns as an explicit first-person voice, but hovers omnisciently throughout the story. As with “The Yellow Wallpaper,” the major themes are introduced at the start. We also know that the marriage will fail, right from the first sentence.

The story starts with the couple’s marriage and then moves rapidly through their first years together and the early years of the children:

It was typical of this couple that they had a son first, then a daughter, then twins, son and daughter. Everything right, appropriate, and what everyone would wish for, if they could choose. But people did feel these two had chosen; this balanced and sensible family was no more than what was due to them because of their infallible sense for choosing right.

The narrator is commenting, again and again, on the “intelligence” of this couple stated in the opening line. Unlike Gilman’s protagonist, there is a sense of freedom here, even if it is presented somewhat ironically. The verb “to choose” is used three times in the passage above.

The story gradually narrows its focus onto Susan, the wife and mother in the Rawlings’ marriage. As the children age, she finds herself both bored and yearning for time to herself. She takes over a room in the house and then, when that gradually turns into another family room, she takes a room in a small hotel. When that room doesn’t work out, she finds another, more anonymous hotel where she stays in room nineteen.

It is in this room that she finally finds some sliver of happiness:

For the most part, she wool-gathered—what word is there for it?—brooded, wandered, simply went dark, feeling emptiness run deliciously through her veins like the movement of her blood.

This room had become more her own than the house she lived in.

There are certainly echoes of Virginia Woolf here. And just as in “The Yellow Wallpaper,” the original impulse fades and disappears before the story ends, the protagonist caught up in a different way of behaving. Here, the “intelligence” that’s cited at the beginning returns several times in the opening of the story; as with the passage on choice, Lessing repeats the phrase in a single passage:

There was no need to use the dramatic words “unfaithful,” “forgive,” and the rest: intelligence forbade them. Intelligence barred, too, quarrelling, sulking, anger, silences of withdrawal, accusations and tears. Above all, intelligence forbids tears.

The switch to the present tense at the end of that passage signals to the reader that while the narrator is recounting a story that occurred in the past, the rules continue to exist in the present. There have been changes, for sure, in the lives of women, but many things remain the same. After this point in the story, the word “intelligence” disappears: the marriage has failed, and as it was based on intelligence, it makes sense that the word disappears as well.