Fracking, Glove Making, and Elevator Inspection: Industry in Novels

I delighted in Alexandra Petri’s column, “An Easy Guide to Writing the Great American Novel.” A writer must be able to laugh, kindly, at herself, and perhaps less kindly at others, especially when those others are extremely successful.

One of Petri’s must-haves in the great American novel is a “painstaking description of an intricate craft or a science thing that the average reader will not be able to fact-check, which is fortunate because it is such a lovely metaphor.”

I hadn’t even realized this was a thing. Of course it is a thing, and I love it. And even worse, I should probably figure out a way to do it in my own novel, which is set largely in a recording studio. So far there is quite a lot of tape moving from reel to reel, with hissing and whirring and clicks and silences that are something more than silences. But the writers I admire do something much better. Instead of slathering details of the specialized trade everywhere, they distill it into one or two scenes that resonate through their novels without exhausting the reader.

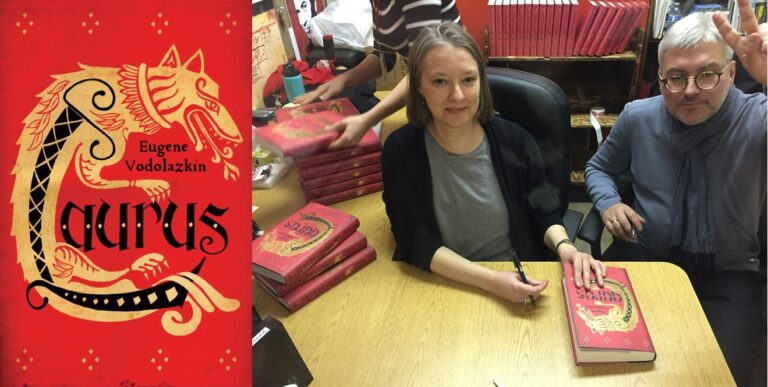

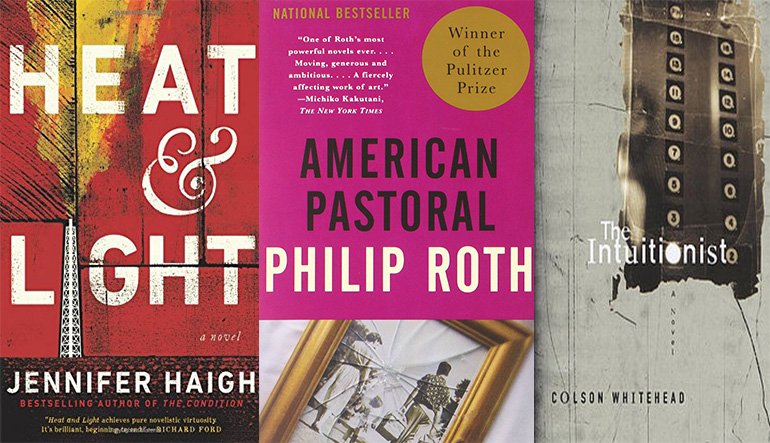

In Heat and Light, Jennifer Haigh tells the story of a coal mining town gone bust and then seemingly reborn when a natural gas company starts buying up land rights. It’s a sweeping book, with a large cast of characters, and Haigh spends time building the characters and the world before she shows us fracking.

“By six the sun is up, the air warming. The bravo crew is tripping pipe. According to procedure it takes five men to change a drill bit, five men to pull the drill string from the hole. The actual truth is somewhat different. Three joints of drilling pipe weigh more than a pickup truck, and yet the floor hands, Brando and Jorge, do all the lifting. This is true of racking pipe, true of most things. A drill rig is a hierarchy like the rest of the world.

The trip goes smoothly, it would seem to the only observers, the darting barn swallow, the numberless gnats rising in clouds. Seen from above, the men are larger than birds and bus, but only a bit larger. A drill rig isn’t scaled for humans.”

Later she shifts to the point of view of the supervisor.

“WARNING NO ENTRY WITHOUT SUPERVISOR

DANGER PINCH POINT

Herc has yet to see a sign that tells the simple truth: of all the calamities that can happen on a drill rig, falling is the likeliest. The easiest way to kill yourself is simply missing a step. He has seen up close what a three-story fall can do to a body. He’d do anything to wipe that picture from his mind.

DANGER

AVISO

PELIGRO

It’s a truth most people never have to learn, that the human body is simply a bag of blood.”

Haigh moves from the distant third person of the choreographed routine of changing a drill bit to Herc’s close third person. These men and their machines are violating the land and possibly poisoning its people, but they’re not safe, either.

The glove factory in Philip Roth’s American Pastoral is a classic example of an obscure craft made clear in a way that serves the story. Swede Levov’s daughter has recently been implicated in a bombing and disappeared. A young woman posing as a student comes to his glove factory to interview him about his business. Rita is receptive and reminds him of his daughter. He becomes pedantic, telling her, “We’re going to make you a pair of gloves and you’re going to watch them being made from start to finish.”

They work their way through the factory from the top down, an echo of a tour he once gave to his daughter’s third-grade class. They linger at the cutters’ table.

“A lot of licking went on, a lot of saliva went into every glove, but, as his father joked, “the customer never knows it.” The cutter would spit into the dry inking material in which he rubbed the brush for the stencil that numbered the pieces he cut from each trank. Having cut a pair of gloves, he would touch his finger to his tongue so as to wet the numbered pieces, to stick them together before they were rubber-banded for the sewing forelady and the sewers.”

At last, Swede presents Rita with the pair of finished gloves, even telling her to “always draw on a pair of gloves by the fingers.” After she accepts the gift she reveals that she’s his daughter’s emissary, a radical who despises capitalists like Swede.

In The Intuitionist, Colson Whitehead creates an alternate America in which elevators and their inspectors are central. In one camp are the Empiricists, inspectors who use traditional methods of evaluating the machinery. In the other camp are the Intuitionists, upstarts who communicate with the elevator on a “nonmaterial basis.”

Whitehead blends his own inventions—including a theoretical elevator—with cold hard facts about elevators. (He lists American Standard Practice for the Inspection of Elevators in the acknowledgements.) In a flashback, Intuitionist inspector Lila Mae Watson is a child and her father reads to her from an elevator company’s catalog.

“Her father read, ’Lifting Power-Gear Combination. For Universal Hoisting Machine, as illustrated below, showing the ‘Belt Attachment’ by which the machine is in in use.’ That means if anything goes wrong, that will hold the elevator up. So it won’t break.”

Lila Mae has recently inspected and passed an elevator that went into freefall. An Internal Affairs investigator thinks it’s sabotage.

“The cable snapped. That’s new Arbo alloy cable. You could lug a freighter with that stuff, but it comes in two somehow. The cab itself had those new Arbo antilock on them.”

Whitehead is not just writing about elevators. He’s writing about racial struggle. The elevators are a metaphor, but first he makes us marvel at their very real intricacy and fragility.