Getting Lost between China and Taiwan

Taiwan is not China. Meet a Taiwanese person and one from mainland China and the difference is akin to the difference between an English person and an American. The schism goes beyond geography and flags. The rifts between the island nation and its gargantuan neighbor helped shape Taiwan’s literature.

Taiwan is not China. Meet a Taiwanese person and one from mainland China and the difference is akin to the difference between an English person and an American. The schism goes beyond geography and flags. The rifts between the island nation and its gargantuan neighbor helped shape Taiwan’s literature.

The Japanese colonized Taiwan around 1895. Chiang Kai-shek fled from mainland China to the island and ruled for a while, having fled with the Kuomintang (Chinese Nationalist party) against Mao Tse Tung’s rising power in 1949. Taiwan was recognized as the official seat of Chinese government but when the UN no longer recognized it as such, it rescinded Taiwan’s UN seat. These are common themes in literature from the island of 23.4 million people, as are its diminishing international relevance and the shift from agriculture to industry.

Two pieces of literature demonstrate struggles of the modern Taiwanese and its indigenous peoples today: Li Ang’s novel, The Lost Garden, translated from the Chinese by Sylvia Li-chun Lin with Howard Goldblatt; and Song Zelai’s short story, “Jingzhen, Taiwan, 1978,” translated by Nancy Tsai. Both works of fiction tackle adjustments of a rapidly modernizing island (Californians, New Yorkers, and Floridians might find commonalities in their real estate-centric work) and contain other similarities threaded through like exquisite lacework.

Li Ang is the pen name of Shih Shu-tuan. Readers early on glean her feminist perspective but with The Lost Garden, a bouquet of extended metaphors, she takes her literary career to new heights by revealing the dark side of modernization. The novel was originally published in 1990, three years after the White Terror Era that saw four decades of martial law in Taiwan, and was the first novel-length work of literature to recreate the Era. A French translation was published 13 years ago and the US just got its English translation in November.

“What separates us from China is more than spatial, temporal, even cultural distance; it is more like a gulf between hearts,” Li Ang wrote in her introduction to the English translation. “Taiwan has been luckier than most countries, for it became democratic without a bloody revolution … Democracy and freedom have made it possible to write about taboo subjects,” unlike many Asians who can only do so by living in other countries.

Li writes of a protagonist, Zhu Yinghong, whose childhood memories include watching her father being taken away for dissent during Chiang Kai-shek’s rule and then later returning, only to hole himself away in his Lotus Garden, which is one of two metaphors that intrigue readers through the book. Father ignored pleas to plant the garden according to the style of mainland China.

“Why plant trees that won’t do well in the local climate? It’s better to grow indigenous trees and flowers,” Father continued in Taiwanese.“Your children may be born in the year of the dog or the pig but they’re still your own flesh and blood.”

Father follows his passions to the ruin of his family, again a metaphor, though that’s not necessarily to say it causes their unhappiness. Along the way we learn from Father how greed and wealth and technology have spread through the island, a nation that’s not even the size of California.

Rumor had it that the town head had colluded with the KMT government when it relocated to Taiwan, which was how he could suddenly transform himself from a local hooligan into a rich man overnight and become [politically connected].

Come time to represent modern Taiwan in the novel, it’s Yinghong’s adulthood, and that upbringing of attachment to a simpler, more traditional island serves her well as she sets her sights on a real estate tycoon, a self-absorbed, chauvinist playboy.

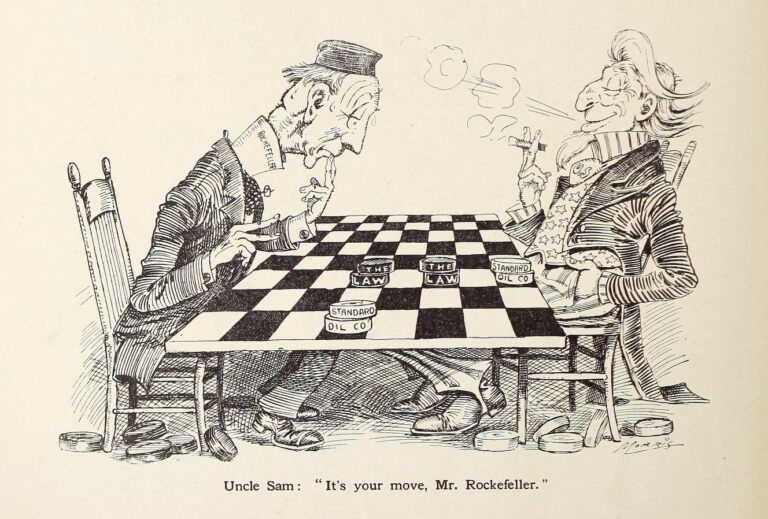

Truthful in their representations of the seediness of capitalism and modernity, Li and Song Zelai might be considered the literary parallel of Sinclair Lewis and Upton Sinclair. In fact if Li’s book represents The Jungle’s Jurgis Rudkis, Song’s short story shows more of its slick real estate agent who deliberately cheats buyers. However the prose style, structure, tone, and pace of this Taiwanese story, written by the prominent Song Zelai, whose stories often center on the struggles and hopes of the Taiwanese people, rings of an oral tale, a fable even.

It pits Wu, a timber and real estate baron known as “a gold digging rat,” against Ding, who uses his position as the town pastor to gain political clout in the 1970s. Wu and Ding are trying to keep the real estate market apace with the population’s rush toward the cities amidst the government’s propulsion toward rapid industrialization. Wu counts on an abacus and builds residential developments with names such as The City of Perpetual Fortune. Ding, a Donald Trump-like character, names his The Grand City of London and uses his connections within the 1% to disable his opponent.

He’d holler remarks at dinner parties, mingle with the working class, and whenever in the presence of high society, figures such as statesmen, religious leaders and scholars, he’d reassume the role of one of God’s chosen people and solemnly address his listener as “Brother.”

As a nation who can still see the shadow of the great recession, we readers can relate when the stock market and real estate crumble. “Jingzhen’s high society was first to feel the blow. You could practically see the pomade glistened class squirming with anxiety.”

The worst part of the battle takes place not as the market climbs but when it collapses. It ending leaves the reader feeling dirty and disgusted. Is it a battle of modernism versus traditionalism, rich versus middle class, greed versus moderation? That’s for the reader to decide.