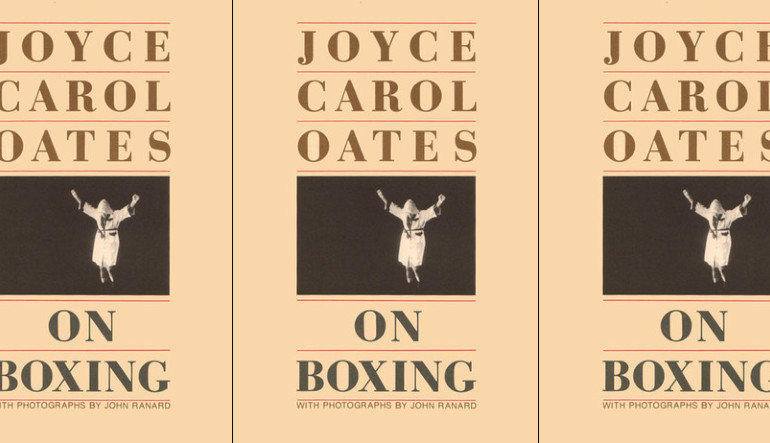

Grant Boxing Your Favor: On Joyce Carol Oates’ On Boxing

Under Review: On Boxing by Joyce Carol Oates (2006, Harper Perennial, 271 pages)

It’s an awesome and unlikely image: Joyce Carol Oates, the gaunt and whispery living legend of fiction, eagerly and appreciatively watching Mike Tyson—yes, that Mike Tyson—spar and grunt his way through his daily training session in quiet Catskill, New York. This, followed by a deep and reflective conversation about the finer points of the younger man’s craft inside his home. This meeting really did take place, once.

Indeed, before his oft-lampooned face tattoo, before the ironic appearances in the Hangover movie franchise—even before he infamously gnawed off a chunk of Evander Holyfield’s ear in the middle of a match—Mike Tyson was an electric heavyweight prospect of boundless and terrifying potential, with the future of the sport sitting prone for him to grab. This is the moment when Oates interviewed Tyson, and the resulting piece of journalism is collected in her book On Boxing, along with five other meditations and reviews, equal parts spiritual and encyclopedic, on the same sport.

Oates does not approach boxing as if the competition were a bizarre, brutish circus sideshow; she doesn’t watch it like a Southern belle watches a horse race, nose pointed skyward. Her knowledge of boxing is deep and heartfelt, constantly recalling not just the technical results but also the complex psychological implications of gobs of title

fights across so many decades. Even though I’ve never personally kept up with boxing, her enthusiasm for the sport is infectious, sending me to YouTube mid-page to load up footage of the greats.

It’s not really so bizarre that Oates found a passion for this testosterone-flooded past-time: the parallels between the arts and athletics are many, especially in an individual sport like boxing. The individual writer approaches the blank page each day just as the individual boxer must continually approach the ring’s blank canvas. On Boxing quotes from a personal letter of Max Schmeling (who acted as stand-in for all of Nazi Germany as he split a pair of fights with Joe Louis in the 1930’s): “Artists, grant me your favor—boxing is also an art!”

Oates goes so far as to compare the unveiling process of a book’s publication date to the night of a fight:

That which is “public” is but the final stage in a protracted, arduous, grueling, and frequently despairing period of preparation.

We are told by Oates that it is not the damage inflicted in formal fights but rather the rigors of training for those matches—a process that stretches both body and soul taut to the point of snapping—that tends to lead boxers to their early retirements. It’s a sentiment with which every writer, pile of crumpled, failed drafts flowing over and out of the trash bin, can sympathize.

There is a key difference between writing and boxing, however, especially when it comes to the moment of publication/fight. Namely: the writer is not (typically) exposing themselves to any risk of getting their nose punched askew, their jaw socked out of place, their skeleton forcefully realigned. In writing there is no direct opponent, dancing out of the corner with gloves swinging. Boxing has so arrested its fans because each new fight finds two individuals who have submitted themselves to very real and heightened stakes, both professionally and personally. Oates appreciates these stakes as a feature, not a bug, of the sport:

Boxers are there to establish an absolute experience, a public accounting of the outermost limits of their being; they will know, as few of us can know of ourselves, what physical and psychic power they possess—of how much, or how little, they are capable.

With Tyson specifically the stakes have always felt abnormally high. He is a bazooka amongst rifles in terms of his ability to inflict harm on his opponent or, increasingly, upon himself. Professional fighters usually fight three or two or even one fight a year, so grueling are the cycles of recovery and preparation; in his first nine months as a fighter, Tyson fought in fifteen. Since he knocked out every one of his opponents, eleven of them in the first round, he left the ring unscathed and thus bypassed the recovery stage completely, at one point taking on and then taking out a new opponent three times in a single month.

Footage of Tyson’s second professional fight, set somewhere dingy in Albany, shows how he can eviscerate a fellow professional while hardly looking interested in the process:

Boxing certainly features levels of adrenaline and volume that writing and the arts don’t have. But the apparently otherworldly inspiration that fuels the boxer in training isn’t, as it may first seem, the knowledge that their next opponent could be working that little bit harder and gaining even a tiny extra edge. Rather, the boxer’s focus is accessible to the opponent-less writer, too, in his or her private toil.

Because there’s only one explanation why a lightning-fast hulk like Tyson would lose three out of his last four fights, the latter two to fighters who were hardly belt-wearers. His ferocious id finally yanking itself free of its chain, Tyson bathed in the worldly pleasures that were so freely accessible to him, instead of training, as he once did in Catskill, with “monastic devotion.” Those final fights were effectively lost before the first-round bell rung. The actual competition was always within the self.