Grapes and Crowbars: Undocumented Labor in Helena Maria Viramontes’s Under the Feet of Jesus

In the opening pages of Helena Maria Viramontes’s first novel, Under the Feet of Jesus, teenage Estrella, her siblings, her mother Petra, and her mother’s lover arrive at a two-room bungalow by night and unpack their meager belongings—a few pairs of clothes, blankets, cooking supplies, and the children’s documents, which Petra keeps under the feet of a Jesus figurine. The stillness of the night belies the labor that awaits them in the morning, as piscadores picking grapes in California’s Central Valley. Not far from the house, Alejo and his cousin, two teenage boys working in the same fields as Estrella and her family, steal peaches that they will offer to the family.

The plot of Under the Feet of Jesus examines the oppression that a family of mixed status face working in an industry that, at once, depends on their labor and treats individual laborers as expendable. Estrella picks grapes with Alejo until he is caught in the field during a pesticide spray and becomes gravely ill. Despite their limited means, Estrella’s family cares for him until he becomes so sick they have no choice but to go to the camp nurse. There, the nurse keeps her fee even though she’s done nothing but tell them Alejo requires hospitalization. Without this money, Estrella and her family won’t have enough gas to make it to the hospital to save Alejo’s life.

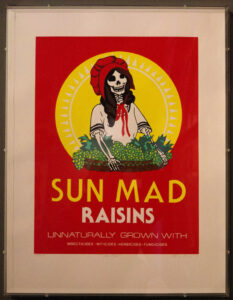

Throughout the novel, Estrella is confronted by the cruel neglect of the American agricultural industry to migrant workers. To reach the camp store, Estrella and her family must dash across a busy highway, and once there, the produce is bruised and remaindered, unlike the perfect vegetables and fruits they pick. Estrella and Alejo are teenagers, yet they work in the fields alongside other children and adults, engaged in the back breaking work that is so unlike the image of the happy, red-bonneted woman on the Sun Maid box that Estrella compares herself to. The unstable nature of migrant work itself, as well as fear of La Migra, puts pressure on the family. “It was always a question of work,” Estrella reflects early in the novel, “and work depended on the harvest, the car running, their health, the conditions of the road, how long the money held out, and the weather, which meant they could depend on nothing.”

Viramontes, the child of migrant workers, came of age in East Los Angeles during a period of intense Chicano resistance, and cultural touchstones of radical Chicano movements are deeply embedded in the novel. Estrella harvests grapes, a highly symbolic crop to the farmworkers’ rights movement, as the five-year Delano grape strike and boycott, begun in 1965, resulted in one of the United Farm Workers’ greatest victories. Estrella’s observations of how different she is from the woman on the Sun Maid box pay homage to artist Ester Hernandez’s 1981 work Sun Mad: “The sun was white and it made Estrella’s eyes sting like an onion, and the basket of grapes resisted her muscles, pulling their magnetic weight back to the earth. The woman with the red bonnet did not know this.”

Homages to Chicano movements temper the hopelessness of the characters’ situations, as does Viramontes’s egalitarian approach to storytelling. The narration flows uninterrupted among the consciousnesses of all the major characters, allowing their nebulous desires to develop along the constellation of the novel’s plot, signifying that despite the uncaring forces of global capital, teenagers fall in love, babies are conceived, and lives have meaning because they are intricately connected to other lives. Despite their poverty, Estrella and her family care for each other because no one else will, and they care for the stranger Alejo because his family is not there to.

When Estrella must take drastic action in the camp nurse’s office to save Alejo’s life, she does so unhesitatingly, wielding a crowbar until the nurse returns the exact amount of money she’d taken from them, allowing them to get enough gas to take Alejo to the hospital. “The oil was made from their bones,” Estrella observes as they fill up the tank, “and it was their bones that kept the nurse’s car from not halting on some highway, kept her on her way to Daisyfield to pick up her boys at six. She had figured it out: the nurse owed them as much as they owed her.”

Estrella’s act may save Alejo’s life, but it doesn’t go without the possibility of retribution. As migrant workers afforded little protection under the law, her family fears the police or La Migra will be awaiting them when they return to the bungalow, should the nurse report them. They have used the last of their money to drive to the hospital, and without money, they can’t make it to another job. As Alejo lays semi-conscious in the backseat of the car on the way to the hospital, he chides Estrella for her violence, saying, “Can’t you see they want us to act like that?” To which, Estrella responds, “Can’t you see they want to take your heart?” Despite the fact that the family’s lives are endangered by Estrella’s decision, it is clear that it’s the only one she could make.The interwoven narratives of Estrella, her family, and Alejo cast against a plot driven by the forces of global capital, allow Estrella a transcendent—if bittersweet—moment of empowerment.