Growing Something from Ash

The owl house my grandfather built is empty, and my grandparents’ orchard is filled with ghosts: my mother, him, a former version of myself. Branches, hung with weighty fruit, used to lift toward the sky. Animals, jack rabbits and ground squirrels, once scattered through the rows. Now, crows stand at the base of the persimmon trees, stabbing their beaks into rotting fruit.

In the attic, tangles of spiderwebs fill the grated steel walls. My mother’s things have been processed. What’s left now is what I stored when I left for college: a heavy citrus box and one Rubbermaid container, the top dotted with insect remains and mice excrement. I have not removed its lid for nearly two decades.

Before I return to my own home with these containers, I walk into the orchard and stand underneath a persimmon tree. At my feet, the soil has dried into a fist-like shape. The ground splits open like a mouth, desperate to drink. Craggy branches bow down, lifeless, their anemic leaves bent and water-starved. The sun shines between the once fleshy leaves. Even the light feels hopeless.

In the garage at home, I pull the top off the citrus box. Inside are stacks of my college notebooks, essays composed in my sloppy, eighteen-year-old handwriting spill over each page. At the bottom of the box are a few books: Shakespeare, Ibsen, Henry David Thoreau’s Walden. I take them upstairs.

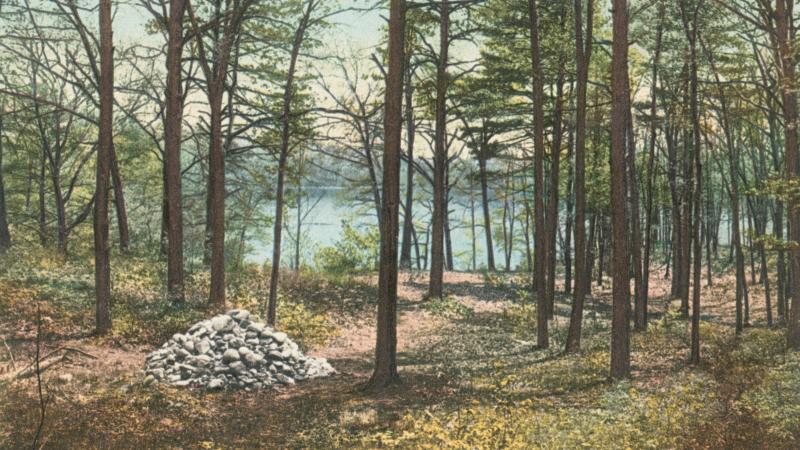

My copy of Walden is old, hardbound, hugged in a decrepit emerald green book jacket torn at the edges. At its center is a golden rectangle and a bird. An editor’s note suggests that Thoreau held his ear “close to Nature’s voluntary and confiding breast.” I have no memory of this book, though its smell is familiar, its pages barely worn. I read it in one sitting. At Walden, Thoreau meets the “wilder and more thrilling songsters of the forest,” like the scarlet tanager, the whippoorwill, the wood-thrush. At the pond, everything is alive—even the ghost-like mist has a purpose to rise and retreat to the woods. The water becomes a “lower heaven.” Dry land “floats.”

I return again to the opening page. Thoreau goes to live at Walden, he says, “deliberately,” to front only “the essential facts of life.” “I did not wish to live what was not life, living is so dear,” he writes, “nor did I wish to practice resignation, unless it was quite necessary.” An effortful turning away from melancholy signals to me a precipitating condition of loss. By then, I had been trying unsuccessfully to turn away from it myself. Death seemed to always have me in its grasp—my only bird, a sorrow-filled singer, resting on my shoulder.

Some research unveils the major grief which drove Thoreau to the woods: one day his brother, John, cut his finger, and the next week he was dead. The death—a mix of tetanus layered onto a lifelong plague of tuberculosis—sunk Thoreau. Afterward, his good friend and mentor Ralph Waldo Emerson’s young son also died. Then, by accident, Thoreau set a fire which burned hundreds of acres of land to ash. Yet, soon after, there is Thoreau, watching through the windows at Walden as “a fishhawk dimples the glassy surface of the pond and brings up a fish; a mink steals out of the marsh.” He is not ascribing pain to the light, to the fruit. He is watching what is alive, and relishing in it.

My grandparents planted persimmon saplings the year I was born. In one photo, I sit in the dirt, pouring the soil over my head. The trees were always so full of life. We’d pull the pulpy globes from the branches, sink our teeth into their meat before casting the remains into the ditches for the sparrows.

While my grandfather rode a rusted red tractor through the lined rows, my sister and I chased the grill in our well-worn Reeboks. Sometimes a rabbit would get caught in the tilling disc, my grandfather forced to pry its carcass from the metal, a haunting reminder that the orchard was alive so much that it could also be killed. We peeled dandelions apart with our fingers and ran wild through the orchard like the animals, the evening light a slash in the sky. There, I saw how with time you could make a thing alive: from saplings to trees, from trees to firm branches matured under sun and sky. At night, the peacocks ran from the adjacent property, dropping their emerald feathers in the dirt. In the morning when we’d collect their jewels, I’d brush the barbs against my face.

My body grew in that orchard, year by year. A baby to a child. I spent summers evenings walking through the trees, touching the shapes of the leaves, the light smeared across the sky in a melted palette. I married my husband under the owl house.

That time was over. Now, the death bird is there, always singing in my ear. But “Walden” pulses with recognition of life, as do other essays I read, “Autumnal Tints” and “A Winter Walk.” So do other transcendentalists’ work I discover, like Emerson’s “Nature” and Margaret Fuller’s Summer on the Lakes.

What strikes me isn’t their impassioned attention to the natural world, but how they managed to replace the heartache of death. Was nature an escape from sorrow, or was it the contriver? Soon after the death of Emerson’s wife, he documents how examining specimens sheltered him from missing her. “In the presence of nature,” he writes, “a wild delight runs through the man, in spite of real sorrow.” In Fuller’s work, I find more of the same: a resistance. While the death of her father brought immeasurable loss, she writes, “let us be completely natural; before we trouble ourselves with the supernatural. I never see any of these things but I long to get away and lie under a green tree and let the wind blow on me.” Similarly, it is as if Thoreau flips the tiles of his sorrow over with the woods, shrinking his sadness with each recognition of the material world. “Death is beautiful when seen to be a law, and not an accident,” he writes. “It is as common as life.” Their joy despite their loss seems endless.

How could they do that? I wondered. Evolving towards delight felt so out of reach. Everything was gray to me.

My mother recorded dreams, quotes, fears about mothering two young daughters alone. I find notes about bird feathers and sunsets among them. She collected rocks on the sink’s edge, buried small crystals in each potted plant. My grandfather, too, was preoccupied with nature: animals and their conservation. Both Emerson and Thoreau kept journals. In Laura Dassow Walls’s biography, Henry David Thoreau, she describes him scribing his own entries into the margins of John’s notebook where he recorded nature observations. Thoreau writes of holding a brood of chicks in his hands on his brother’s pages. I find this entirely striking. It is the opposite of erasure, his recording an act of conjuring the dead, calling the ghost to the scene to bear witness to life.

I try logging my own joy. In the winter I lift my pen and the first entries come in summary of things beloved to me: my husband, our cats. But then I hoover at the lines. It feels very difficult to name a thing provoking an active emotion. I find myself defaulting to gratitude, a more passive experience. Soft sweatpants, I write one day. A partially filled parking meter. Discounted ribbon. This goes on for months. I note conveniences like finding parking in a busy part of town. A windless run in the park. There is birthday cake, a negroni on a sunny day. A meme my sister sends set to an old Billy Ocean song, my mother’s favorite. These things do bring delight, but they lift nothing. The bird still waits, trills of death.

Then one day, I go on a hike with my husband through a gorge, a rocky path laid flat with water and time. At the end is a small water cave formed by boulders. The water is fecund, dirty, but I see something in it. I set down my pack and water before wading in. I move gently towards the fixture on the wall, crouching under a series of rocks as I approach.

There glued to it, basket-shaped, no larger than half a cantaloupe is a bird’s nest composed of straw and wood and desiccated leaves. Held delicately at its center are two perfect eggs abandoned and tired with time: one blue, one pink. In its corner is a sprig of new green emerging from underneath.

The labor of that nest and the new life pushing through an end bend my face. I put my hand to my mouth. Immediately, I felt I saw my mother there, my grandfather. They were standing in the light holding hands.

Soon after, my journal entries slowly turn to life. One day I note a new leaf on my fiddle fig. The next, a tiny bead of a lemon emerging on the citrus tree. Later that week I write, the first magnolia bloomed in the park! Life soon spills over the pages: The bison running through the field, then dropping to roll in the dirt. New pink buds on the plum blossom trees. Daffodils on the edges of the trails. Three days in April my joys are flowers themselves, new growth in the garden: foxgloves their little bells speckled with light; marigold heads; cosmos’ tissue-thin petals. Thoreau writes in “Autumnal Tints,” “We cannot see anything until we are possessed with the idea of it, take it into our heads—and then we can hardly see anything else.” By summer, it is hard to remember each note of joy I observe during my runs in the park through miles flush with color, birds, rainbows I see on the horizon during a drive home after rain.

Perhaps I had been waiting for exuberance. Perhaps, the former version of myself, before the loss, expected only ecstatic experiences to unfasten me from sorrow. Does time change me, or the attention to life? Perhaps both. Both have borne hope.

Thoreau moved to Walden long before he published what would later become his most famous work. In that time, his sister died, and Fuller was killed in a shipwreck. I read that the earliest version of Walden lacks some of his preoccupations with the nature surrounding him. I’m left wondering, if in his revisions of his own reflections during that time, he turned away from death because it was too hard to look at anymore. Instead, by letting nature in, with its enduring commitment to life, it inscribed itself in the place where his loss sat.

This new joy is quiet, less intense. The veiny pink interiors of a certain kind of magnolia petal, its form as rigid as a strip of new leather, hold an enchanting mystery of color. Today I stood in the orchard and looked: a speck of moss spread across the tree bark’s tributaries. A sparrow’s yellow mouth rustled a twig into a nest. Small swells of joy break through. But there are long days of sorrow still. There is longing for the ghosts. This new attention does not put the ghosts out, or erase the memory of what I miss. Instead, I try inviting them in, to observe with me. The bird and I have grown used to living together. I raise my face to the sun’s light. Maybe one day the bird will fly away.