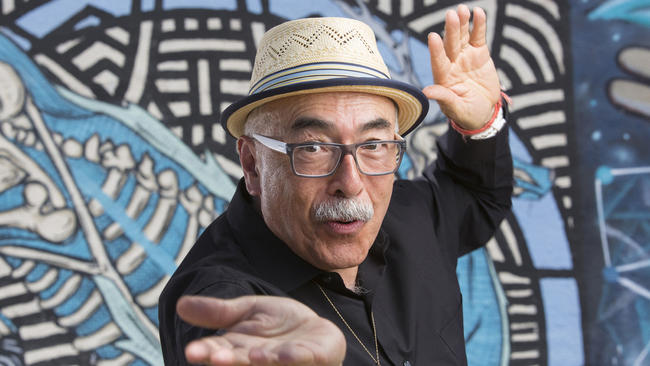

Half the World More: Juan Felipe Herrera and the Centering of Chicana/o Letters

Juan Felipe Herrera being named our 21st U.S. Poet Laureate is special for a few reasons. He is the first Latino U.S. Poet Laureate in history, but also an unlikely if necessary one. It’s no obscure fact that his writing has historically been underappreciated, undercelebrated even. Herrera’s writing has not, historically speaking, been the kind of writing mainstream America—and I should add mainstream Chicana/o letters—has readily embraced. True, Herrera is integral to the chicana/o literary canon, but his writing is also less commercial, less likely to be anthologized than some of his contemporaries who have played into the publishing industry scripts: Write about the cocina, don’t write about Darfur; write about the barrio, don’t write about geopolitics. The beautiful thing about Herrera is that he writes it all. And he writes it well. He refuses to be contained. Which is, more or less, the brown writer’s road to obscurity—being uncontainable.

It’s true what the papers say: he’s impossible to pigeonhole. You could try to describe Juan Felipe Herrera’s poetry though you’d only be trying really. Herrera can be a formalist poet as easily as he can be a polyrhythmic one or a free verse one or a blank verse one—a jack of all hands. Even within a poem, you look for a pattern and its there for a stanza, changed in the next stanza, shifted to an image-based stanza in the next, changed to symbols in the next. You look for his next book of poetry and he’s written a novel. You pick the novel up for prose and find the entire thing is written in verse.

The one thing you could say about Herrera is that the sound is always there. That cataloguing rhythm you get in poems like “Señorita X: Song for the Yellow-Robed Girl from Juárez” or “Grafik.” That same anaphora in Herrera’s “Blood on the Wheel” like the first lines of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl or Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass.

Our 21st U.S. Poet Laureate belongs in the same trajectory as those poets. His style is undeniably influenced by them. But also like Whitman, like Ginsberg, Herrera is arguably one of the premier chroniclers of contemporary America. Poems like “Water Water Water Wind Water” about hurricane Katrina or “Half-Mexican” paint an ideologically and racially complex portrait of the contemporary United States, contrary to some of the polite, simple narratives we, as a nation, have bought into in recent times, both in politics and literature.

The scope and political depth of Herrera’s poetry is the lifeblood of his work though, some argue, it’s also the same thing that had, until recently, kept him in relative obscurity outside of Chicana/o letters. That kind of criticism isn’t so much an indictment on Herrera, the writer, as an indictment on political writing in general—too on-the-nose, too low-hanging.

Ni modo, as the old folks say. Those kinds of arguments are still around: the belief that “good writing” can only be produced in a vacuum. Small stories about small people doing small things in a small world. Herrera is the photo negative of all that—his writing booms with life. And I’d argue that it’s not only Herrera’s political instincts that opened up his own poetry, but the thing that opened up, too, the scope of possibilities for what other chicanas/os can write about.

Who says we only have to write about Juarez? Who says we only have to write about our families or misogyny or poverty or low-riders or Mexico or Texas or California or Orange Groves? The political consciousness of Herrera’s work centers chicana/o letters more than it decenters it, I think. I think of Kipling’s poem, “The English Flag” when I think of Herrera’s work. I think of that line in the first stanza: “And what should they know of England who only England know?” Expanding on the sentiment of that line, I’d ask “And what is Chicana/o letters without a global consciousness? Without a critical, outward looking eye? Without a wide scope? Like Herrera’s.”

I think this is the kind of thing Sherman Alexie talks about when referring to the line in Adrian C. Louis’ poem, “Elegy for the Forgotten Oldsmobile.” That line that made him decide to be a writer: “O Uncle Adrian! I’m in the reservation of my mind.”

When I read Herrera’s work, I think of his lines as words that allow me to honor the rez while leaving it at the same time. He gives me permission to look out, to wander. Hererra’s work says, not only is it possible, it’s your duty.