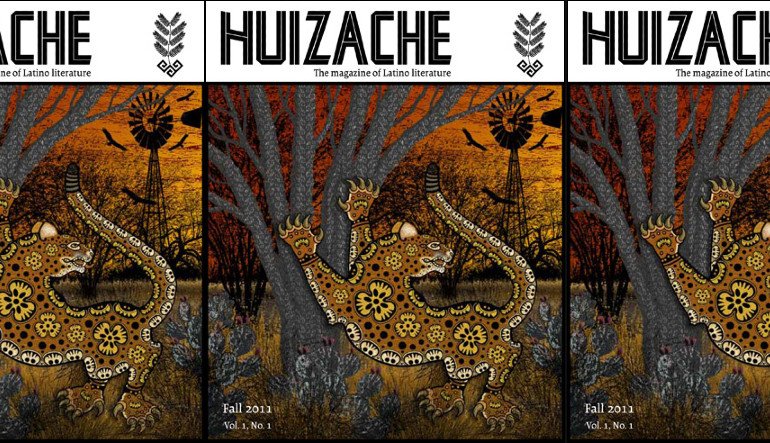

Huizache: The Biggest Little Secret in Texas

As far as literary journal subscriptions go, I only maintain three. I’m one of those writers, and for my sins I mostly miss the great early pieces of writers I come to love years later. This is especially true of new Latina/o writers, who I think most people miss for various reasons, not least of which is the serious lack of hard-hitting journals that focus on new Latina/o work.

That’s not to say there are none though. Huizache, which is probably one of my favorite journals right now, has quietly carved out a space for Latina/o letters both old and new. Over the past three years, they’ve published work by Sandra Cisneros, Domingo Martinez, Héctor Tobar, and Lorna Dee Cervantes, almost without a blip on the literary radar.

The journal itself, one of the great projects of Dagoberto Gilb and based out of the University of Houston’s Centro Victoria, has developed a sort of cult-following amongst writers and academics, especially here on the east coast. You get the feeling reading Huizache that you’ve stumbled upon this great, secret thing that’s manifested outside the MFA vs. NYC conversation, but still a thing which includes some of the greatest writing today. You’re just as likely to read Sherman Alexie’s newest work in Huizache as you are to read the first poems by a young Chicano writer flying completely under the radar. Which is sort of the magic of this journal.

With Huizache you’re always aware that there’s a lineage at play, that the curation by its editor, Diana López, is not only an amalgam of old and new but one working as pair of arms knotted in a gripped embrace: the old vanguard pulling up the young guns and the young guns pulling along its lineage, learning from it, building upon it.

I remember it was Huizache that first introduced me to the work of Eduardo C. Corral and Alex Espinoza, and of course the incredible artists who grace Huizache’s covers like Chuy Benitez, Gronk, and Cesar A. Martinez. For me, the physical objects themselves—almost square with heavy pages and matte finishes—are incredible artifacts but also really essential platforms. Huizache is centralizing great Latina/o writing in a time when it’s become so decentralized, especially among millennial Latina/o writers who came of age in the absence of the Macondo workshops, since revived by the Guadalupe Cultural Arts Center, or outside the geographical scope and reach of other organizing agents like Canto Mundo and Nuestra Palabra.

For many millenial Latina/o writers, like myself, who sought community in places like VONA, the Callaloo Workshops, the Asian American Writers Workshop, Kundiman, and Cave Canem, this journal is a home for us in a way even if it’s not trying to be. It’s a place where we go back to check up on our gente and check in to read the newest words, look at the newest art. Because like the huizache plant itself, that work is everywhere even if we don’t see it right away, even if it’s blended so as not to disturb the very literary landscape it inhabits (as many would have it).

Which brings me to my favorite factoid about the huizache tree itself: it’s pervasive and impossible to kill. It’s always growing.