In Sickness: Feeling Unwell in the Wake of the U.S. Election

In the days after the U.S. presidential election last month, people became sick. Friends, colleagues, and mere acquaintances narrated their symptoms. Some were harboring throbbing headaches, others had gnawing stomach pain that they couldn’t shake. There were colds that seemed to magnify in scale and snot as the unbearable weekdays lurched toward the weekend. One friend told me she had inexplicably woken in the middle of the night on Wednesday and vomited fiercely before returning to bed—the first sleep she had in a 24-hour news cycle that wasn’t presaged by the slick glow of headlines read by phone light. For me, it was long bouts of insomnia: waking in the cold hours of early morning, unable to lull myself back to sleep against the backdrop of encroaching social and environmental menace.

These symptoms, I started to realize, were symptomatic. In life, as in literature, when we feel unsafe, we become unwell. The stress of our vulnerability manifests in aches and pangs, in churning stomachs and tightened temples, in sheer exhaustion. The racism, sexism, bigotry, and xenophobia of our body politic, its enunciated sicknesses this election season, seemed to seep into our own bodies—at least some of them.

Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s now nearly compulsory short story, “The Yellow Wallpaper” (1892), came to mind. The semi-autobiographical narrative is staged as the spiraling diary entries of a young wife and mother removed to the remote country by her doctor-husband for a rest cure to treat “a temporary nervous depression.” He assigns her a sickroom with bars on the windows and “a schedule prescription for each hour of the day,” expressly forbidding her to write. Far from a fictionalized flourish, Perkins’s doctor in real life mandated her silence: “And never touch pen, brush or pencil as long as you live,” he wrote. The narrator languishes in this house, feeling “fretful and querulous.” Unable to furnish an appetite, she becomes weak and sleepless. Her husband camouflages his gaslit cruelties, preserving her inconsolable loneliness and prolonged silence, in soothing tones and diminutive pet names. When she becomes obsessed with the wallpaper in her sickroom, it is not only a preoccupation with her own oppression, the imagined captive woman behind the curlicues and arabesques of the patterned paper. Instead, it is the internalized suffering that is all around her, in the big “colonial mansion” to which she has been deposited with its optics and indexes of past brutality. “It makes me think of English places that you read about,” writes the narrator from the U.S., “for there are hedges and walls and gates that lock, and lots of separate little houses for the gardeners and people.” These now absent “people” are perceptible in the buildings and grounds—in property—their identities imaginable in the specifics of U.S. race and class abjection, relatable in their long-suffering silence. In the space of what we call America, we are all implicated in each others’ silences.

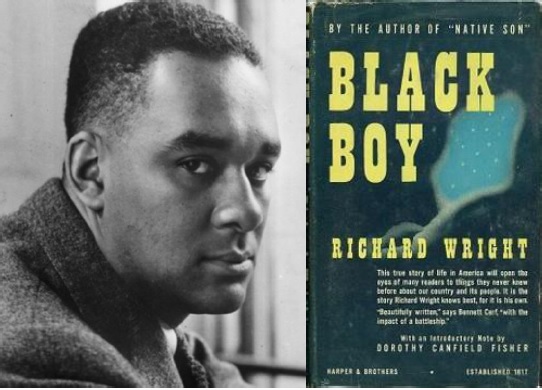

Nursing her own swollen sinuses and a sore throat during election week, a friend reminded me of the slow convalescence in Richard Wright’s Black Boy (1945). The memoir, recounts Wright’s youth and his family’s painful transit through Jim Crow America. Their sheer poverty produces a spectrum of pain for young Wright who knows early the bodily anguishes of hunger and discomforts of cold. His mother—dispossessed of her inheritance because of the government’s refusal of her father’s pension for his debilitating service to the Union Army; abandoned by Wright’s father; on the run from the men that lynch an uncle for want of his success in Arkansas; and generally weary from hours of menial and degrading work in other people’s kitchens to feed and protect her two vulnerable boys—is perhaps the most tragic character in the book. She slowly becomes an invalid, suffering strokes and palsies in mysterious and likely treatable successions. She and her children become wards of her family. “Her illness gradually became an accepted thing in the house, something that could not be stopped or helped,” writes Wright agonizingly and presciently. “My mother’s suffering grew into a symbol in my mind, gathering to itself all the poverty, the ignorance, the helplessness; the painful, baffling, hunger-ridden days and hours; the restless moving, the futile seeking, the uncertainty, the fear, the dread; the meaningless pain and the endless suffering. Her life set the emotional tone of my life, coloured the men and women I was to meet in the future, conditioned my relation to events that had not yet happened, determined my attitude to situations and circumstances I had yet to face. A somberness of spirit that I was never to lose settled over me during the slow years of my mother’s unrelieved suffering, a somberness that was to make me stand apart and look upon excessive joy with suspicion, that was to make me self conscious, that was to keep me forever on the move, as though to escape a nameless fate seeking to overtake me.” Then as now, the fate that Wright describes isn’t nameless. It is the physical attenuation, “the wearing out” to borrow a term from Lauren Berlant, of some people over others in the wake of intentional government decisions that beget lives lived under slowly encroaching and assured death.

Simon J. Ortiz’s poetry collection from Sand Creek (1982) registers this kind of protracted pain too. Set in a VA Hospital in Colorado toward the end of the Vietnam War, not far from the site of the 1864 Sand Creek Massacre, Ortiz achieves a range-finding, long view of white supremacy and U.S. exceptionalism. The space of the hospital serves as a site to diagnose and defer the maladies of Native American communities in the book’s present and past. He takes on the mantle of Whitmanian tradition begun by old Walt when he laid bare the hospital tents of the U.S. Civil War. Weaving between complaints and conditions, poetry and prose, the physically maimed and psychically wounded returned Vietnam veterans and the Cheyenne and Arapaho men, women, and children systematically murdered and mutilated by the Colorado cavalry in the nineteenth century, Ortiz produces the lethargic hum of lives made vulnerable and dispensable. “VA doctors tell him / not to worry. / That’s his problem. / His cough / is not the final blow,” he says of one veteran. In the expanding U.S. frontier, he writes of the plague of ghost towns, “Spots appeared on their lungs. / Marrow dried / in their bones. / They ranted. / Pointless utterances / Truth did not speak for them.” And traveling back in time to Arapaho sovereignty, Ortiz notes an originary dis-ease, “Somehow / it was impossible / for them / to understand true safety.” The horror and despair of from Sand Creek is not newly relevant, nor merely American. But, it may help us grapple with a world that will likely grow more unsafe, mostly for populations who were always already vulnerable.