Interview with Joel Brouwer

Like anyone, I have to contend with my own stupidity all the time—forgetting things, ignoring essentials, not listening—but one of my latest and most grossly idiotic moves was waiting until 2010 to read Joel Brouwer. That’s too kind, actually: I didn’t wait, it wasn’t like I’d seen his stuff and ignored it before, I’d just somehow missed it. How does one miss work like this? Brouwer’s poetry’s some of the most satisfying work I’ve read in I don’t know how long—gorgeous, yes, and moving, certainly, but satisfying like a song can be, like a meal. It’s silly to try, without quoting at length, to note the ways his poems simultaneously create a desire in the reader and then, by the poem’s end, satisfy that desire, but it’s 100% worth it to read a sample (the latest set from Poetry is particularly remarkable).

Cutter: If you were writing in another genre, who’d you like to write like and why? Who do you dig in fiction or non-fiction? Would you want to write like that? Do you presently want to?

Brouwer: As something of a shut-in and a homebody, I enjoy fantasies of exploration; I would like to have had Ryszard Kapuściński’s life and to have written what he wrote. To be that close to history as it’s happening, and then write about it so beautifully. I really want to be a playwright but whenever I try to write dialogue it sounds stupid to me so I quit. I would like to be Suzan-Lori Parks. I would love to have written any of Sarah Kane’s plays but I’ll pass on the suicide. I’d like to have written David Mamet’s American Buffalo or the screenplay for House of Games. I’d like to be David Hildebrand Wilson, founder of the Museum of Jurassic Technology. I write a lot of criticism but almost exclusively in the form of book reviews, and I wish I could be a more synthetic essayist. I would like to have been Montaigne, Orwell, or Emerson. Or Edmund Wilson. I would like to be Cynthia Ozick. I would love to write like Joan Didion, whatever that means; I’m still trying to figure it out. I tried one time to write a novel and I had Didion’s Play It as It Lays open on the desk for a month, but instead of writing my book I just kept rereading hers. I love photography and wish I was Beate Gütschow. Or Thomas Struth. I love music and wish I was Kim Gordon. I wish I was Ralf Hütter. I love movies quite passionately but somehow I tend not to fantasize about being a movie director. I think it’s because the technologies of film are so completely mysterious to me.

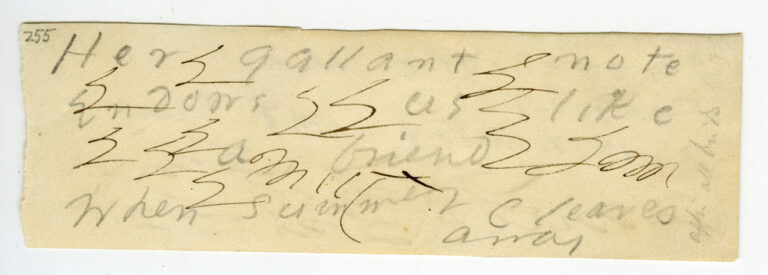

Cutter: What’s the first sexy or suckering phrase you read which made you point at the page (or whatever) and deep breathe-in and go, shit, that’s what I want to do? And, if you can: what was it about that line?

Brouwer: “Ya ya from a mile high I crook you up warm, rabbit arm.”

I read that line of Jean Valentine’s in a rented room in Burlington, Vermont in 1992 and realized that my sense of the available ranges of tone in poetry was far too constricted. I resolved to stop composing so carefully, to stop being so calculated in my striving after effects, and “just go on my nerve,” as Frank O’Hara put it. I have not yet succeeded in this effort, but I’m still trying.

Cutter: What’s a poem of yours which has been published, and it’s out and available, but which you’re still not 100% satisfied with? Why?

Brouwer: All of them. If I had to describe why, I’d say that every poem I’ve written seems to me either to have gone too far or not gone far enough. They’re either too neat or too much a mess, too melodramatic or too robotic, too over-determined or too misty, etc.

Cutter: On a different/other track: what’s a thing of yours you’re working on which you can’t seem to nail down? Is there some ‘problem’ you’re working at/toward, consciously, in hopes of solving? (those notions of ‘problem’ and ‘work’—you can use as squishy of terms as you wish).

Brouwer: I want to be able to write with authority and humility about occasions where representatives of my government have tortured and murdered innocent people. If I could figure out how to do that, I’d be quite pleased. My progress toward this goal has been slow.

Cutter: I’m really curious about the fundamental unit of poetry, for you. This feels academic-ish to ask, but I mean it: And So feels full as a book, as a collection; it doesn’t feel slopped together, but coherent, symmetric, even. Obviously, of course, you write in words and lines and etc., but do you think of your work primarily in book-contexts? Do you build your work in book contexts?

Brouwer: Yes and no? I write the poems that occur to me. When I have a pile of them, I try to discern groups within the pile that have both consistencies and interesting inconsistencies. That’s how I get started working on a book manuscript. I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with books that are miscellanies, and I don’t think there’s anything inherently wrong with books that are organized around a particular subject or theme. Both of these routes feature pitfalls, however. I think even a self-professed miscellany has to have some element that holds it together as a single work, even something as simple as a consistent line or voice. And “project” books risk dullness. My favorite books are both broad and deep.

The fundamental unit of poetry for me has become the sentence. I didn’t intend for this to happen, but it has. More and more I find that my composition process involves writing sentences, and then arranging them in an order that seems productive, exciting, or ideally, both.

Cutter: Your work is essentially narrative—it’s charged, certainly, but the muscles of the poem seem narrative, seem to flex hardest because of the story involved. First: do you feel/see/write that way? Do you recognize it and/or try to sidestep it? Second: if it’s true, if this is fundamentally narrative stuff, how do you think narrative poetry is being pursued/apprehended at present in American poetry (yes, this is the elliptical question)(and: this question’s highly personally motivated–this is stuff I find myself thinking lots lately about).

Brouwer: Don’t you sometimes find it difficult to tell the difference between narrative and lyric poetry? I don’t really think about the distinction very much when I’m writing; it seems like something for someone else to decide. I’ve got enough to worry about already. It’s my impression that these days “narrative” is something of a derogatory term, deployed when the poem feels overly obvious in its agenda, overly determined, overly pat. In the last few decades of the 20th century, we saw a lot of poems which recounted poignant anecdotes in plain language — William Stafford’s “Traveling through the Dark” is the epitome of the style — and I think starting in the 1990s and continuing to this day, people started to get sick and tired of all these epiphanies in the vegetable garden, epiphanies at the child’s school play, epiphanies while driving the car. The ensuing backlash was (or is) fuelled stylistically and theoretically by a huge variety of figures, and so can’t be easily described or characterized, but I think you could say with some confidence that an aversion to anecdote was (or is) a fundamental part of it. But narrative hasn’t gone away, and won’t so long as humankind continues to consent to a linear theory of time. It’s amply present in a great deal of poetry that purports to have none. I remember once hearing Michael Palmer read. He introduced a poem of his by telling us a long story about how the poem was about taking a walk through a park in St. Petersburg with a friend of his. Then he read the poem, which bore no discernible trace of the anecdote he’d just told us. Was that a narrative poem?

Cutter: Your stuff deals in more direct ways with ‘real world’ issues than lots of poets I know of working presently—war, social injustices, etc. Wax however you’d like (passionate, poetic, dismissively) on that fact (or, hell, disagree, that’s great) on that aspect, if you’re at all interested.

Brouwer: Discussions of this important issue too often descend into pieties and cant. Poets moan about how poets don’t engage with contemporary political realities. Poets moan about how crappy poems turn out when they attempt to e.w.c.p.r. Poets moan about feeling pressured to e.w.c.p.r., when in fact, they moan, poetry’s responsibility is to transcend history rather than engage with it. I find all these positions boring and simplistic. Any time you hear anyone begin a sentence with the words “poetry should,” “poetry shouldn’t,” “poets should,” or “poets shouldn’t,” I suggest you immediately put your earbuds back in and dial up your favorite piece of music. Whatever that piece is, it’s going to tell you more important things about poetry than your interlocutor was about to.

I didn’t realize it at the time, but I began writing poems because I was both seduced and revolted by generalities. I had a compulsion to find exceptions to rules, yet I was obsessed with rules, with what we called, in undergraduate theory seminars, “totalizing systems.” I searched for them, gave myself over to them, adored them, couldn’t stop myself from wanting to destroy them. The Sermon on the Mount. Levin mowing with the peasants in Anna Karenina. Adorno, Habermas, Cioran. Whitman’s capaciousness. Schopenhauer! Always looking for the last book I’d ever need, an explanation I could live with forever. Always thinking I’d found it, and then losing it or ruining it, and then berating myself for my disgusting and fatal bourgeois weakness, my inability to dwell in uncertainty. Poetry presented itself as a refuge and relief. In writing a poem, I address only specifics and particulars. Complete comprehension is not only not required, it’s undesirable. Relationships between ideas or images not only may be, but should be accidental, improper, gratuitous. Making art is the only job I know where you succeed by failing to solve problems and fail if you do solve them.

Obviously, then, I have nothing prescriptive to say regarding whether poets should e.w.c.p.r. or not. I have no “shoulds” for poets. It is also the case that I, for one, am far more interested in reading and writing poems that e.w.c.p.r. than I am in reading and writing poems that do not.

Cutter: I don’t know why it occurs to me to ask, but what sort of music do you listen to? Your work—again, this has to do with the book, though also with those most recent poems from Poetry—seems so balanced, so satisfyingly built. Does this have a musical background? For instance: are you really into rap? Way off on all of that?

Brouwer: I listen to a lot of things. Classic jazz (Ben Webster, Sonny Rollins), African pop (Orchestre Poly-Rythmo de Cotonou, Orchestra Baobob), Delta and Chicago blues (R.L. Burnside, Muddy Waters), minimalist classical composers (John Adams, Steve Reich), German and Japanese electronica (Cluster, Ellen Allien, Nobukazu Takemura), the hip-hop of my youth (Gang Starr, Tribe Called Quest), ambient post-rock (American Analog Set, Tortoise), disposable European house music (Kruder & Dorfmeister, Stephane Pompougnac, Paris DJs). I think in general I like things that feature repetitive structures into which slight variations are introduced, or threatened to be introduced. The title of my favorite Stereolab album may describe it best: I like Dots and Loops. Is this preference evident in my poems? Yes, I think so.

Cutter: The more I read your work, the more I’m struck by sort of patterns–there seems to be a huge heave toward symmetry in lots of ways and then, lately, in those last poems in Poetry, there seems to be a dive toward parallelism. This probably won’t deviate much from your answer before about the fundamental unit of poetry for you, but I’m curious (especially given that you’re most interested in the sentence and ordering them) about symmetry, parallelism, pattern, etc. However you want to touch that one’s fine.

Brouwer: Again, dots and loops. Have you heard John Adams’ Shaker Loops? I want my poems to feel something like that (though hopefully not that dramatic). Symmetrical but unstable.

Cutter: What’s the view out your window?

Brouwer: I just got some heavy curtains to try to keep the cold out, so I no longer have any view.

This is Weston’s second post for Get Behind the Plough.