Kissing Walt Whitman

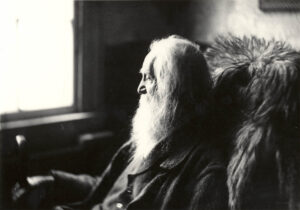

When I was growing up, there was a framed drawing of Walt Whitman hanging in our house. It was a sketch my mother had done, a flawless reproduction of a photo of Whitman with his flowing white beard, hair curling around his ears. My mom had explained who this man was, her favorite poet, but when I was very young, he was an old man who looked maybe like someone’s grandfather, or maybe even Santa Claus during his time off, when he wasn’t bringing presents to children.

When I was growing up, there was a framed drawing of Walt Whitman hanging in our house. It was a sketch my mother had done, a flawless reproduction of a photo of Whitman with his flowing white beard, hair curling around his ears. My mom had explained who this man was, her favorite poet, but when I was very young, he was an old man who looked maybe like someone’s grandfather, or maybe even Santa Claus during his time off, when he wasn’t bringing presents to children.

When I finally read Whitman, then, I was disabused quickly of any notion that he was a gentle, chuckling, grandfatherly old man. I saw all the things we consider “Whitmanesque”: the energy, the exuberance, the empathy. And one thing that my mother’s serene portrait had not prepared me for—the eroticism. Whitman might have been the earliest sexy poet I read, but he remains perhaps the best. Where many erotic poems make me feel like a voyeur, Whitman’s ability to double the figure of the lover and the figure of the reader never fails to thrill.

“Whoever You Are Holding Me Now in Hand” is my favorite example in Leaves of Grass. Whitman begins with a first stanza that is constructed to sound lofty and ominous, the voice of a God-like author who addresses the reader as “[w]hoever you are holding me now in hand.” He booms, “I give you fair warning before you attempt me further / I am not what you supposed, but far different.” There is no clear attempt yet to woo the reader, or to link the reader with a beloved figure, although the line hints at this doubleness, since both a reader or a lover could conceivably be holding Whitman in his hand. The “fair warning” of the third line is then unpacked in an exhausting run-on sentence with darkly ominous vocabulary; the speaker says, “The way is suspicious, the result uncertain, perhaps destructive,” and that the reader’s “novitiate would be long and exhausting.” The long sentence also has a highly imperative feel, with the speaker repeating the command “you would have to” twice, and ordering the reader to “release me,” “let go your hand,” and “put me down and depart.” The vocabulary and the long, charged sentence leave the reader unable to get a breath, echoing Whitman’s relentless tone. Such a barrage seems antithetical to Whitman’s desire for a committed reader, but with the fourth and fifth stanzas Whitman necessarily softens, introducing the tender and quite erotic note of the title—a note that characterizes many of his other poems of address to readers.

The reader is immediately aware that Whitman is constructing a new tone by the rhetorical shift signaled by the words “or else” at the beginning of stanza four, which directly follows the order to “put me down.” The word “or,” in fact, is repeated three times within six lines, representing the possibilities that Whitman entertains of a reader willing to submit. The tone following the rhetorical shift is accompanied by a shift in imagery and vocabulary. Once the possibility suggested by “or else” reveals itself, Whitman rushes headlong into a reverie about the ideal reader, and the intense connection—love—that would exist between poet and reader. Imagining being read, the imagery shifts from a way that is “long and exhausting” to a clear and open natural vista, in which reader and book are the sole figures. Whitman tenderly imagines being “possibly with you on a high hill” or “possibly with you sailing at sea.” In the last few lines on this stanza, the increasing intimacy in tone leads the speaker to a surprising suggestion: “Here to put your lips upon mine I permit you / With the comrade’s long-dwelling kiss or the new husband’s kiss, / For I am the new husband and I am the comrade.” This morphing of reader into lover seems to come upon the speaker with an associative suddenness akin to the reader’s surprise. Here, the doubling of reader and lover figures crosses distinctly over into the physical with the action of the kiss, the only physical action in the poem that cannot be reconciled with the normal interactions between a reader and a book.

The tenderness that overwhelms the fourth stanza crescendos to eroticism in stanza five, in which an unmistakably erotic tone is created by vocabulary like “thrusting,” “throbs,” “heart,” “hip,” and the repeated refrain of “touching you.” Whereas the lover superseded the reader at the moment of the kiss in the previous stanza, Whitman here achieves a perfect doubleness of suggestion, since it is his book, after all, which will be touching the reader’s hips and thrust under clothing.

Just as Whitman’s speaker gives us a glimpse of the possibility of consummation, he returns to the tone of the first half of the poem. “But these leaves conning you con at peril / For these leaves and me you will not understand,” he decides. This is a vision of the future in which the reader has failed to commit to understanding. He ends with the same request that closed stanza three: “depart on your way.” Although the poem ends with this dismissal, it is in the tone of those two tender earlier stanzas that the reader finds the key to the poem’s meaning. By offering a glimpse of a readerly utopia, and then scorning the reader’s ability to enter it, Whitman presents a real-life challenge to his audience that we cannot help but want to meet. Like the best lovers and the best poets, he leaves us wanting more.