Launching

Today, my first book launches. It’s kind of a wonderful word, launch: such propulsive force in its sound. Such muscular, fearless leaping.

To mark the occasion, I thought I’d take a look at launchings of various kinds in literature. Not gradual beginnings, not slow evolutions into different forms, but sudden catapults into the new. The different shapes a true leap can take.

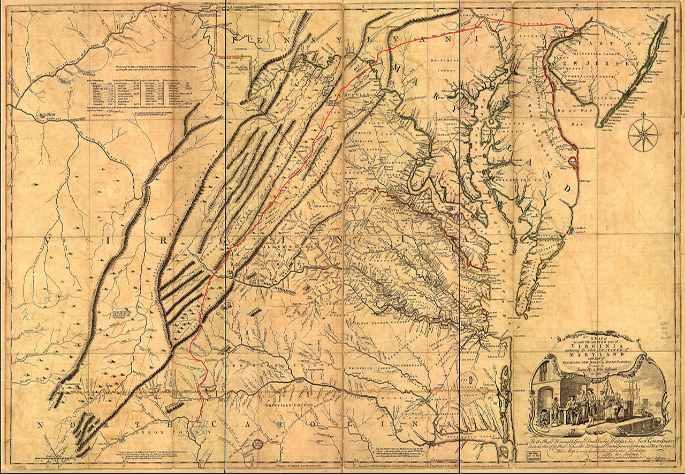

1) The voyage

We have been empowered to strike north from Mt. Arden into the great interior as far as the 28th parallel of latitude. This in order to determine whether a mountain range or other major height of land exists in that vicinity…

If such a height of land does exist, then everything north of it must necessarily flow into an as yet undiscovered watershed: a vast inland sea.

—Jim Shepard, “The First South Central Australian Expedition”

Jim Shepard’s characters are often setting forth on quests, bold explorations, which rarely end well. In this case, the combination of the title and this excerpt tells us everything we need to know about the forthcoming disaster: this is an impossible quest, a hunt for a body of water we know doesn’t exist. An attempt to find water in this place will necessarily end with the terrible consequences of water’s lack.

Yet the narrator, whose journal entries—trending shorter as the expedition progresses—trace the course of the tragedy, doesn’t have the benefit of our knowledge ahead of time. His conviction is what dooms him—it’s a fatal faith, and it’s steering not just the narrator but all the men on his expedition, with dire consequences. But there’s something beautiful in his belief, too, I think, in his eagerness to follow it where it leads him. His aim is misguided, but at least he’s aiming for something.

2) The new love

He set it up and began to show her and she found herself glowing inside. Somebody wanted her to play. Somebody thought it natural for her to play. That was even nice. She looked him over and got little thrills from every one of his good points.

—Zora Neale Hurston, Their Eyes Were Watching God

This isn’t just any game of checkers. The newly widowed Janie spent her whole decades-long married life as a symbol of her husband’s power: he wanted her impressively aloof and untouchable, in a mold that left no space for her actual self. She’s just met Tea Cake, and his first act is to try to draw her into the social fabric she’s so long been separate from. It’s the ease with which he provides a participatory space for her that first wins her over. She is eager to play—to throw herself into playing. There are of course risks to the game, but she’s eager to exercise the right to take them.

3) The new marriage

…I saw myself, suddenly, as he saw me, my pale face, the way the muscles in my neck stuck out like thin wire. I saw how much that cruel necklace became me. And, for the first time in my innocent and confined life, I sensed in myself a potentiality for corruption that took my breath away.

The next day, we were married.

—Angela Carter, “The Bloody Chamber”

“The Bloody Chamber” is Carter’s retelling of the story of Bluebeard; to say this isn’t fated to be a happy marriage is an understatement. But at its outset, the union does have a dark kind of magic for the narrator. Along with this beautiful, sinister necklace, her new husband has given her a new vision of herself. Her life has so far existed within certain confines, and he has torn them away. Thus freed, she’s sensing, she might be capable of almost anything. And despite all the terror that this marriage has in store for her, that exhilaration is real, and vivid.

4) Birth

We’re with her, we’re the same as her, we’re drunk. Aunt Elizabeth kneels, with an outspread towel to catch the baby, here’s the crowning, the glory, the head, purple and smeared with yoghurt, another push and it slithers out, slick with fluid and blood, into our waiting. Oh praise.

—Margaret Atwood, The Handmaid’s Tale

The narrator of The Handmaid’s Tale and all of the women who make up this “we” are caught together in a system that exploits their ability to breed and attempts to stifle all other parts of who they are. The birth unfolding in this scene is a fraught event: this woman will have to relinquish her baby to this system. Giving birth itself is an animal act; the human elements that we expect to follow it have been taken from these women. And yet there’s such astonishing excitement in the rhythms of this passage—such awareness that this particular animal act is also a miracle, and that it belongs, somehow, to the whole collective. Despite the sadness and rage that surround this birth, I think we can hear a launch of the truest kind in that last “Oh praise.”

5) The new self

The oldest sister howled something awful and inarticulable, a distillate of hurt and panic, half-forgotten hunts and eclipsed moons. Sister Maria nodded and scribbled on a yellow legal pad. She slapped on a name tag: HELLO, MY NAME IS ____! ‘Jeanette it is.’

Karen Russell, “St. Lucy’s Home for Girls Raised by Wolves”

These wolf-girls, the human children of werewolf parents, have come to their new Catholic school/home to be transformed and tamed. Here they encounter the first real step in the process: renaming. They’ve had ways of identifying one another within their pack before now; those ways, the nuns are telling them, are no longer relevant. They will be called something new, and they must learn to be something new. They’re being prepared for human lives, as docile and polite human women; their old wolf-selves are to be abandoned here. There’s loss in that, which Russell makes heartbreakingly real over the course of this story. It’s a painful, crushing kind of beginning, but it is still a beginning. Russell ties it closely to the process of growing up.

As these characters launch into newness, of various kinds, they encounter new dangers, new costs, new demands. They’re leaving the familiar ground they’ve always walked on, after all—all at once and forever. It’s a risky act. And a hopeful one.