Learning to Listen: an Interview with Susan Power

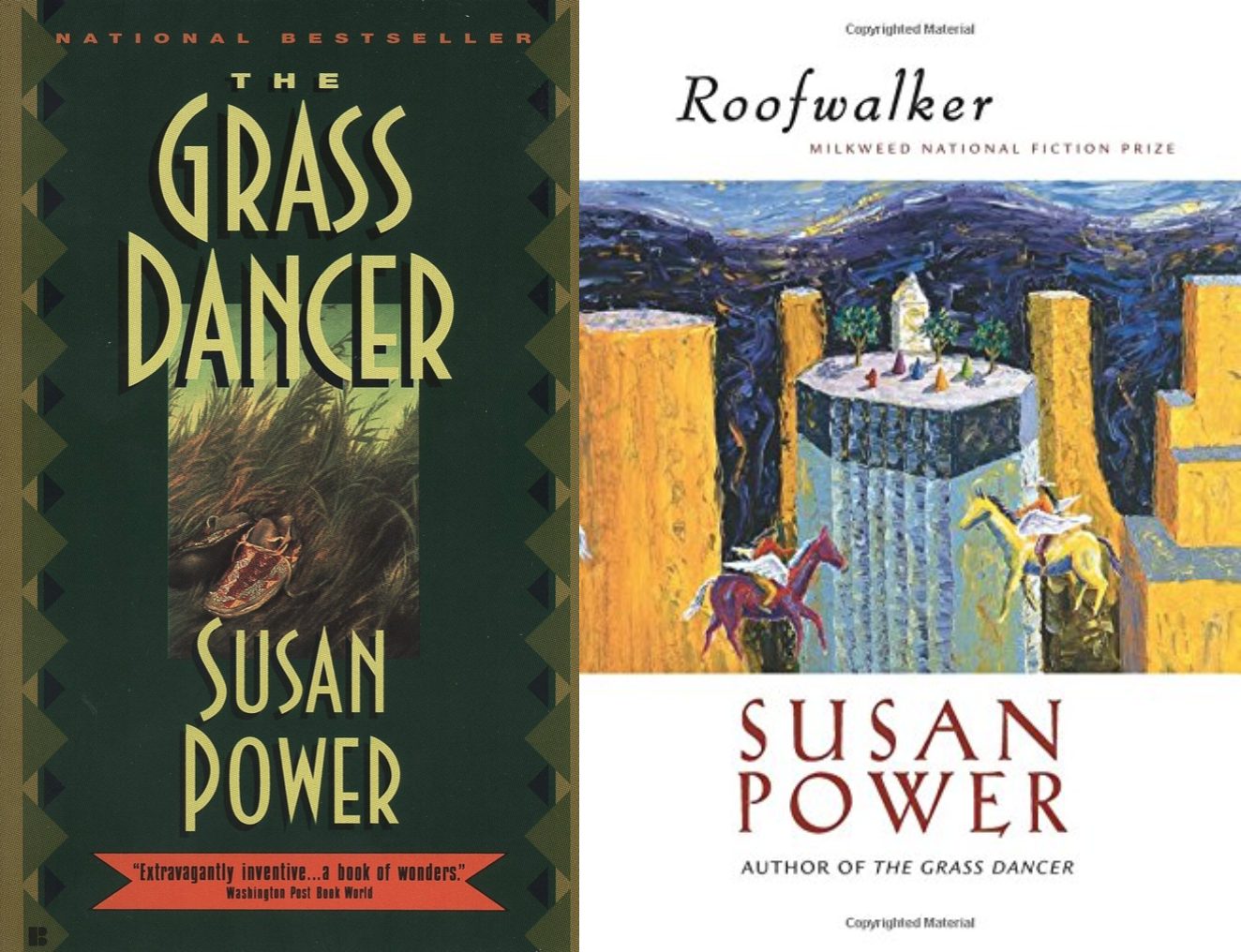

When I first started reading Susan Power’s novel, The Grass Dancer, I knew little about her. We’d met briefly through a mutual friend, and I knew that Susan had been a fellow at Radcliffe’s Bunting Institute. I also knew from her bio that she was an enrolled member of the Standing Rock Sioux tribe and a native Chicagoan, and that her novel was set on and off a Sioux reservation. When I’d finished reading The Grass Dancer near dawn, though (I’d stayed up most of the night reading), I knew that Susan was a writer I’d follow into any territory she chose to explore. Her characters were funny and tragic, pragmatic and soulful, often at the same time…and the story she told was utterly gripping.

I wrote to Susan about her book, and she responded to my letter with the grace and open-heartedness she brings to everything she does. That was more than a dozen years ago. To this day I teach The Grass Dancer—alongside Susan’s essays and stories in her collection Roofwalker—when I talk to students about writerly compassion. Whether her characters are Native, white, or other, Susan weaves together their struggles and dreams with unerring perceptiveness and humor. Her work testifies to the power of a writer’s refusal to stereotype characters or box them into political roles….and to the beauty, wisdom, and delightful human quirkiness that can emerge in even the darkest moments.

RK: When did you realize you wanted to be a writer?

SP: I’ve been writing all my life – even before I could read I filled pages with the letters I knew from the Alphabet song, and would seek out my parents, hold up the nonsense paper and declare: “This is what I have written.” Then I’d tell them whatever story I concocted on the fly. There was such satisfaction in filling those pages with letters, even though I couldn’t yet herd them into words or sentences. The longing was already there. The best gift anyone could ever give me when I was little was a book. But because writing was such a basic element in my life, like breathing, brushing my teeth, I didn’t really consider pursuing it professionally until I’d graduated from Law School and realized I wasn’t meant to be an attorney after all – I was an Arts person and had to honor that calling. So I focused on learning more about craft, in the small bits of free time I had during a lunch break at work or on weekends. I should also say that I’d strenuously avoided studying writing all through high school and college because I’d had such power struggles with teachers in elementary school. Several of them noted my talent, but questioned my subject matter. I would write about the Native experience in Chicago, some of it quite harrowing, only to have teachers ask why I couldn’t write about “pretty things,” didn’t my people “love the natural world?” So, I instinctively protected my voice and vision from their interference.

RK: Which writers are your greatest influences?

SP: When Louise Erdrich began publishing her remarkable novels in the 1980’s (right about the time I graduated from Law School), I fell upon them like a starving person who hasn’t realized she’s hungry. When I was growing up there were not only few, if any, Native American authors being published, there were few Native characters to be found in literature at all, and what few existed were often wince-worthy creations who didn’t bear any resemblance to people in my family or community. I couldn’t find myself or my family in literature. And Louise comes along, with her unforgettable characters who could be relatives of mine, her stories of good medicine and bad medicine, which others would label “Magical Realism” but in my world were familiar, ordinary experiences, and suddenly the world broke open for me. She made anything possible, or so it felt to me. She was such a trail-blazer for a generation of us to follow – she proved that Native stories and voices had a market, a willing readership waiting to be tapped. And the rhythm of her language was like angel-song to my ears. I also want to mention an author whose talk at Radcliffe’s Bunting Institute made a profound impression on me – Marcie Hershman. First she cited the age-old dictum handed down to writers, “Write what you know.” Then she offered another version that has guided me ever since: “Write what you need to know.” Yes!

RK: How would you say your work has evolved in recent years? Are there new issues you’re writing about, or things you feel you’ve left behind?

SP: One recent development is a growing ability to get out of my own way. To set aside the old self-conscious ego, the one who is thinking either, “Well, isn’t that a nice word? Aren’t you clever?” or “That’s dreadful, not lyrical at all.” I had a wonderful acting teacher in high school, Mrs. Ambrosini, who taught us to do our best to focus on the character, their desires and fears and needs, not our own. She said that if we were consciously evaluating our performance in the middle of a scene, we weren’t acting. Art had left the building. I try to write from that place of immersion in another psyche and story, which takes great focus and generosity, confidence and maturity. The moments I’m able to get “there,” to that place of selfless inspiration, are so precious to me. That’s when I’m truly writing what I need to know.

RK: In Roofwalker, you made an unconventional choice to put fiction and nonfiction in the same book. Can you say something about how you came to that decision?

SP: I noticed that even when I thought I was writing a story that had nothing to do with me or my life, there was a thread of connection to memory, to lived experience, once I paid careful attention. I’d written a handful of essays about my family history, and thought it might be interesting to have a collection where a person could read a short story, then read an essay that featured the seed of actual experience which was later spun into fiction. I meant for the book to have these pairings move back and forth between fiction and non-fiction, but my editor thought it would be confusing for readers–a good point, so we created two sections instead. I think we are always writing our story to some degree.

RK: It was a delight to send some of your work to Hala Salah Eldin Hussein, the editor of Albawtaka Review in Egypt. Hala, who makes it her mission to translate English-language fiction for an Arabic-speaking audience, was having trouble finding new stories that she found compelling enough to want to translate, and I had a strong feeling she’d love your work. She’s now translated “Red Moccasins” and published it in Arabic. In an email to me, she discussed your work using words like ‘intricate’ and ‘redemptive’, and talked about the story’s ‘fully-formed characters and unforgettable sorrows.’ Hala wrote: ‘I found [Susan Power’s] work a refreshing affirmation of the strength of ancestry and the nearly unattainable charm of storytelling.’

A Tahrir Square protestor in Cairo finds meaning in your stories set on a Sioux reservation. I know this isn’t the first time your work has bridged geographic and cultural boundaries…in fact, it’s always seemed to me that bridging barriers is something essential to you and your work. Can you say something about the cross-cultural connections you’ve made as a writer?

SP: I was so lucky to be raised in diversity at a time when much of the country was rigidly segregated. Our home welcomed (and often housed) people of all different races and religions, due to my mother’s outgoing nature and political activism. I was raised to honor the traditions and histories of fellow human beings, whatever their origins, and expected to look beyond the end of my nose. So I’m not surprised that characters of various backgrounds have tapped me on the shoulder and offered up their stories – a Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) Marine, just returned from the war in Vietnam, an elderly Norwegian-American considered the “Black Sheep” of the family because he’s so ebullient, even Maryam, my version of the Virgin Mary. The challenge is that in order to truly honor their experience, to be able to write with any degree of authenticity and stand in their shoes, I have to do considerable research. I might not have “earned” their story, but I can try to learn it. I have a wild imagination, but without the research I’m afraid I’ll be relying on stereotypes in my depiction of them, so I try to get as close to the truth bone as I possibly can. I think growing up surrounded by difference has given me the ability to easily “switch heads,” to look at the world from my angle, and then change up the view. When I was younger I was fascinated with difference, measuring the ways we stand apart from one another, focusing on the chasms that separate us. As I get older, I’m moved by the universal, cherish our connections and the hesitant, courageous attempts to reach across valleys of grief and disappointment and betrayal.

RK: What are you working on now?

SP: I recently completed a novel titled, Our Lady of a New World, which took me seven years to write. The opening line is: “This is a Clan Mother story for the 21st century.”

Talk about diversity! I kept waiting for my own people, Dakota tribal members, to show up as characters, urged them along, sometimes pleading, but folks of other backgrounds found their way into my imagination instead. An Ojibwe woman who taught me so much about selfless love, a Kanien’kehaka (Mohawk) woman who taught me that it’s never too late to admit one’s mistakes, a young Kanien’kehaka man from the 1600’s who showed me the wisdom of our Native prophets. This novel, unlike my other books, felt like an apprenticeship I served under the watchful eyes of elders. In order to find the truth of this fiction, the authentic voices, I had to expand as a human being, develop greater compassion, courage, and patience. I had to set aside my expectations and plans, my agenda. And for someone who is all about words, spilling them endlessly from my tongue and my pen, I had to learn the toughest lesson of all: how to listen.