Life as Sisyphean Sport in Anelise Chen’s So Many Olympic Exertions

The rules of her life are killing Athena Chen, the down and out grad student narrator of Anelise Chen’s debut novel, So Many Olympic Exertions. Saddled with a long overdue dissertation on sports history, Athena spins out into an academic and personal crisis when her ex-boyfriend, a brilliant student, kills himself. She is set adrift among the rubble of all the goals she had set for herself: getting her PhD, achieving academic success, triumphing over the “daily resistance of living.” And for Athena, these goals, and the uncomplaining hard work and suffering it takes to achieve them, are the stuff of life. So Many Olympic Exertions shows the limits of living life like a game.

Athena has put so much of her self-worth into achieving a normative “success” to a hilarious degree. She goes to a session of her sister’s recreational swim team and ruminates on how team dynamics motivated her to swim more aggressively without question. “Is that why you joined the team? So you could stop asking yourself why?” she asks her sister, who “shoots her a look,” and replies: “I do it because it’s fun.” Her myopia is absurd, but also oddly relatable for its extremes.

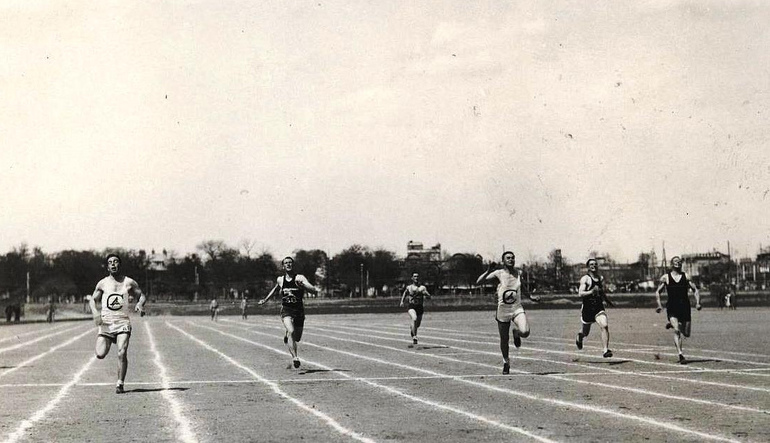

Athena is intrigued by Camus’s Sisyphus, who she calls “the loneliest athlete.” Condemned by the gods to roll a rock up a hill into eternity, Sisyphus, writes Camus, “watches the stone rush down in a few moments toward the lower world whence he will have to push it up again toward the summit. . . . It is during that return, that pause, that interests me.” Athena agrees: “Now it interests me, too.” Chen does beautiful, thoughtful returns in this book, looping around the connections between sports and life, sports and death, and the limits of those through lines. What motivates one to keep going despite death and the gruel, rote work of staying alive? Every sport, like life, appears Sisyphean from certain vantage points. The motivating action and the hard rules of a sport can seem so pointless if one isn’t a believer in the meaning attached to the game. To someone disinvested in the idea of Olympic glory, a gold medal is just a pretty thing to hang around your neck. “When one plays a game, one has to take the rules completely seriously, but at the same time acknowledge that, ultimately, the rules are arbitrary,” writes Chen. It’s play of perspectives that Athena—who vacillates ferociously between caring too much about achieving her goals and facing off the uncaring void of clinical depression—finds difficult to navigate.

“Once you learn what to watch in this game, it is civilized complexity incarnate,” wrote the art critic Dave Hickey of basketball, a sport that, to some, can look just like the dull repetition of teams running back and forth, matching the other for a basket. Hickey’s love for the sport lies in the collision between an individual player’s talent and creativity with the demands of the game. He finds meaning in the beauty that erupts out of these interactions. He learned how to look at it differently. Athena, too, must relearn how to look, and to invent new ways of playing by the demands of life that go beyond losing and winning. Sisyphus’s return is a refusal to give up, but his “triumph” bears little resemblance to a marathon runner crossing a finish line. Athena learns that the lines to hold herself by aren’t as unmoving as those that athletes abide by. She comes to a sort of reckoning with Paul’s death after a visit to his family’s home. Driving back home, she looks out the car window:

Rows of vine shuffle out from the horizon like spokes on a car wheel. My eyes follow the movement from left to right, left to right.

And then I smile. Of course. This is how horizons work. When you look out at the horizon, all the lines culminate in one point. But once you shift position, all lines culminate in another point. Points of horizon change all the time. It all depends on where you’re standing.

Athena’s smile, here, is a small moment of delight that stands out from the slog of depression and shame that she endures throughout the novel. She lets go of the goalposts she had been driving towards and re-figures what to hold herself by. By the book’s end, one must imagine her happy.