Mark Twain and Literary Caves

I find myself thinking about these enclosed spaces underground which appear in literature as setting, metaphor, and plot device. Plato’s Parable of the Cave reflects on the nature of reality. Odysseus is trapped in a cave by the cyclops Polyphemus. In Dante’s Inferno, hell is a vast underground cavern. Nancy Drew is always getting trapped in caves, underground passages, ships’ holds: dark places where, the villains like to say, ominously, “You’ll never see daylight again.”

I spent hours of my childhood underground—not in caves, but in networks of drainage tunnels under I-35 and US 54, some tall enough for a child to walk through, some offshoots that required crawling through claustrophobic spaces. I didn’t want the other neighborhood kids to think I was a coward, so I crawled through with my eyes closed, hoping that I wouldn’t slap a spider or lizard as I inched along. I’m happy that I no longer feel a need to prove my courage by stuffing my body into a concrete tube while traffic thunders overhead and voices echo and daylight is only a sliver of hope way down at the end. Given this, you’d think that I’d have little adult interest in returning underground.

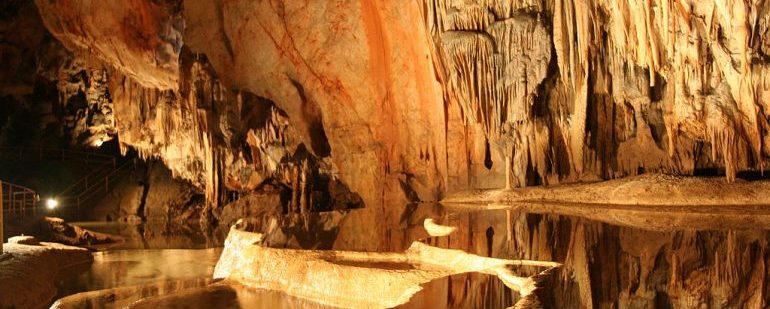

But I can’t resist stopping at the cave that Mark Twain regularly played in as a child in Hannibal, MO. “The memory of a cave I used to know was always in my mind,” he wrote, “with its lofty passages, its silence and solitude, its shrouding gloom, its sepulchral echoes, its fleeting lights, and more than all, its sudden revelations….” The cave he refers to appears in five of his books, most familiarly, Tom Sawyer.

Now, this cave’s entrance is decorated by cutouts of leaping frogs and straw hats, calling to mind the jumping frog of Calaveras County, Tom, and Huck. Inside, cold air blasts us like an air conditioner set at 52 degrees, and we make our way through the narrow, rocky passages that Twain described as “walled by Nature with solid limestone that was dewy with a cold sweat. . . By-and-by the procession went filing down the steep descent of the main avenue, the flickering rank of lights dimly revealing the lofty walls of rock almost to their point of junction sixty feet overhead. This main avenue was not more than eight or ten feet wide.”

The lower parts of these walls have been blackened by more than a hundred years’ worth of smoke from candles and fire. Several passages are covered by the signatures of visitors before writing on the walls became illegal. Others are lined by sparkling calcite deposits once thought to be diamonds until a jeweler quashed that idea.

As in many caves, our tour guide is fond of puns. We hear stories about people who took each other for granite, hit rock bottom, had their worlds rocked, played rock music, and served marble cake at weddings held here, giving their marriages a rocky start. “Hold on to the stalagpipe,” he jokes as we walk across a slippery passage with handrailings made from PVC pipe.

He rattles off facts, points out locations of events from Tom Sawyer, and tells stories. Lots of caves claim that they were once Jesse James hideouts, he says, but this one is one of three that has been verified, and a framed photo of his signature is on display at the end of the tour. The guide points out the place where Becky ran into a “chandelier” of bats. Twain writes about bats in his autobiography: “A bat is beautifully soft and silky; I do not know any creature that is pleasanter to the touch or is more grateful for caressings, if offered in the right spirit. I know all about these coleoptera, because our great cave, three miles below Hannibal, was multitudinously stocked with them, and often I brought them home to amuse my mother with.”

On other cave tours, tour guides have encouraged us to look for shapes in rock formations the way we might in clouds: a reclining potbellied man, a battleship, the face of Santa Claus. Maybe, I think the appeal of caves is witnessing the way the natural world keeps repeating itself in infinite forms of the same patterns. Or maybe it’s the way that caves echo the stage of the hero’s journey in mythology that Joseph Campbell calls “The Inmost Cave,” the place where the hero finds treasure or new knowledge.

“The cave you fear to enter holds the treasure you seek,” Campbell writes. Odysseus consults Tieresias in the land of the dead, Aeneus visits the underworld to find his father, and following an ordeal of being lost in the cave where the book’s villain is hiding, Tom returns, with Huck, and unearths buried treasure. Just as we imagine that we see familiar images in rock formations, caves themselves feel like descending to subterranean levels of consciousness and to the transformative moment of so many stories in western tradition.