The Affair’s Gender-Swapped “Madwoman in the Attic”

In the third season of The Affair, one of the Solloway children comes home excited to tell his mother that he’s participating in a musical version of Jane Eyre. In the show’s typically self-conscious fashion, the child explicitly discusses the novel’s infamous “madwoman in the attic,” Bertha Mason, as a none-too-subtle allusion to the fact that his mother is keeping his drug-addled father hidden away, their very own “madman in the basement.”

But even without that anvil-like reference, the parallels between Noah and Bertha in this episode are already quite clear. Bertha is described as afflicted with a violent insanity, while Noah is in the throes of hallucinations caused by Vicodin addiction and PTSD that ultimately drive him to attack a well-meaning prison guard. Rochester keeps Bertha locked in an attic to protect her from herself, while Helen keeps her husband in the basement, walking in on him in the shower and reading his texts “for his own good.” And in the moment that her child is chattering about Bertha at the dinner table, Helen is keeping Noah hidden from her level-headed, stable boyfriend, just as Rochester keeps Bertha hidden from the virtuous Jane. When each of the “good” partners discover the “madwoman in the attic,” they leave their respective relationships, if only temporarily.

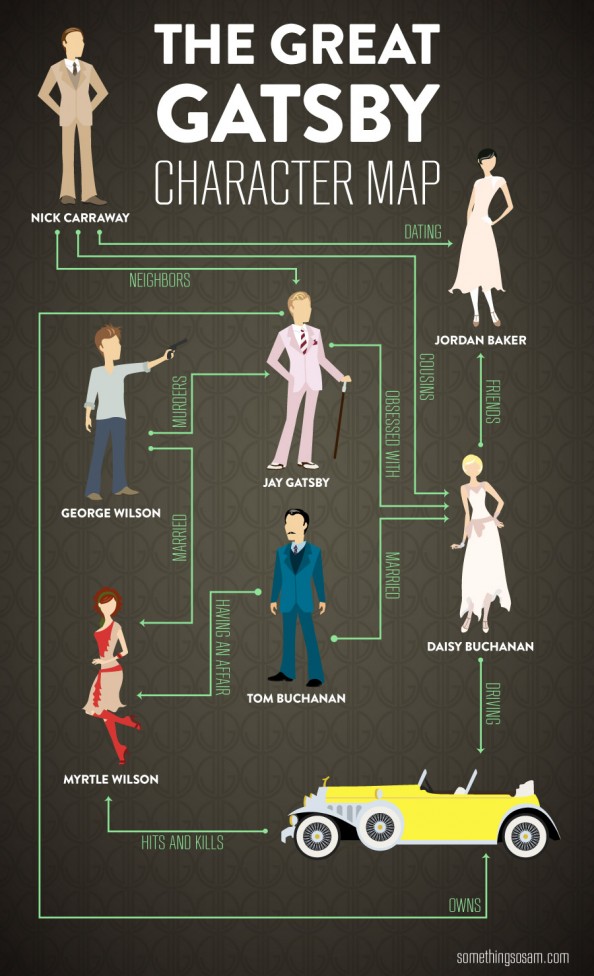

That being said, a proper gender-swapped “madwoman in the attic” is not really possible, nor should it be. The phrase refers to a landmark text in feminist literary criticism by Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar, which drew its title from Rochester’s beleaguered wife. In the book, Gilbert and Gubar claim that Victorian literature divides female characters into pure, angelic women and uncontrollable, animalistic monsters. Bertha is exemplary of the latter trope; when the reader first encounters her, the narrator repeatedly calls her “it,” and claims that “whether beast or human being, one could not, at first sight, tell.”

It grovelled, seemingly, on all fours; it snatched and growled like some strange wild animal: but it was covered with clothing, and a quantity of dark, grizzled hair, wild as a mane, hid its head and face. . . . A fierce cry seemed to give the lie to her favourable report: the clothed hyena rose up, and stood tall on its hind-feet.

As a result, Bertha’s plight has become symbolic of both gender and race-based oppression. In the acclaimed postcolonial novel, Wide Sargasso Sea, for example, author Jean Rhys portrays Bertha as a rebellious young Creole girl named Antoinette Cosway. Her marriage to an unnamed Englishman, who renames her “Bertha,” becomes increasingly toxic and controlling. Her mental illness is attributed partially to her family history, but is catalyzed by her abuse and imprisonment at the hands of Rochester.

In this context, Noah has more in common with Rochester than with Bertha. Rochester married Bertha for her “wealth and beauty,” just as Noah married Helen when he was a poor kid trying to marry into a world of luxury. Once they’re married, Noah repeatedly cheats on Helen (Rochester openly has several mistresses), becomes emotionally abusive, and claims never to have loved her. Similarly, Rochester said of Bertha, “I never loved, I never esteemed, I did not even know her.” Like Rochester, Noah seems to be at a disadvantage initially as a result of his low socioeconomic status, but uses his male privilege to overpower his wife while claiming to be the victim.

In this episode, Noah superficially appears to be Helen’s prisoner, but in reality, he can leave whenever he wants to, and is unfairly burdening his ex-wife (and her doctor boyfriend) with his care. Bertha, on the other hand, is physically restrained from leaving, and is watched by a female servant. Noah tries to draw sympathy by letting his daughter’s boyfriend beat him up, when he’s perfectly capable of defending himself. Similarly, Rochester tries to draw Jane’s sympathy when Bertha tries to throttle him, during which the narrator specifies: “He could have settled her with a well-planted blow; but he would not strike: he would only wrestle.”

Noah’s gendered violence against his “captor,” compared to Bertha’s aggression against Rochester, demonstrates the impossibility of gender-swapping the “madwoman in the attic.” When Bertha finally escapes the attic, she sets the house on fire and commits suicide. She is clearly angry at Rochester, who loses a hand and temporarily his sight in the incident. But primarily, she just wants to burn everything down, especially herself, so she can escape her suffering and oppression. Noah, on the other hand, casually walks upstairs once Helen’s boyfriend is gone, and uses his newfound “freedom” to rape his ex-wife. Bertha asserts her limited power by hurting mostly herself, while Noah asserts his freedom by reminding Helen that he always had the power.

I would say that this is incredibly insightful on The Affair’s part, but I’m not sure how much credit it deserves. The show has its moments, but is definitely not reliably feminist. (The portrayal of the sexual assault itself, for example, is strangely and unnecessarily muddied, since it appears in Noah’s recollection but not Helen’s.) It’s very possible the writers simply thought the situation had parallels to Bertha, and didn’t think much more deeply on the matter. But even so, the episode is at least accidentally astute about gender relations, simply because that’s what they think a white man like Noah would do in that situation. The “madman in the basement” will never be in the same situation as Bertha, and will always be in a position to reclaim his power at a moment’s notice.