Lydia Millet’s Biblical Climate Apocalypse

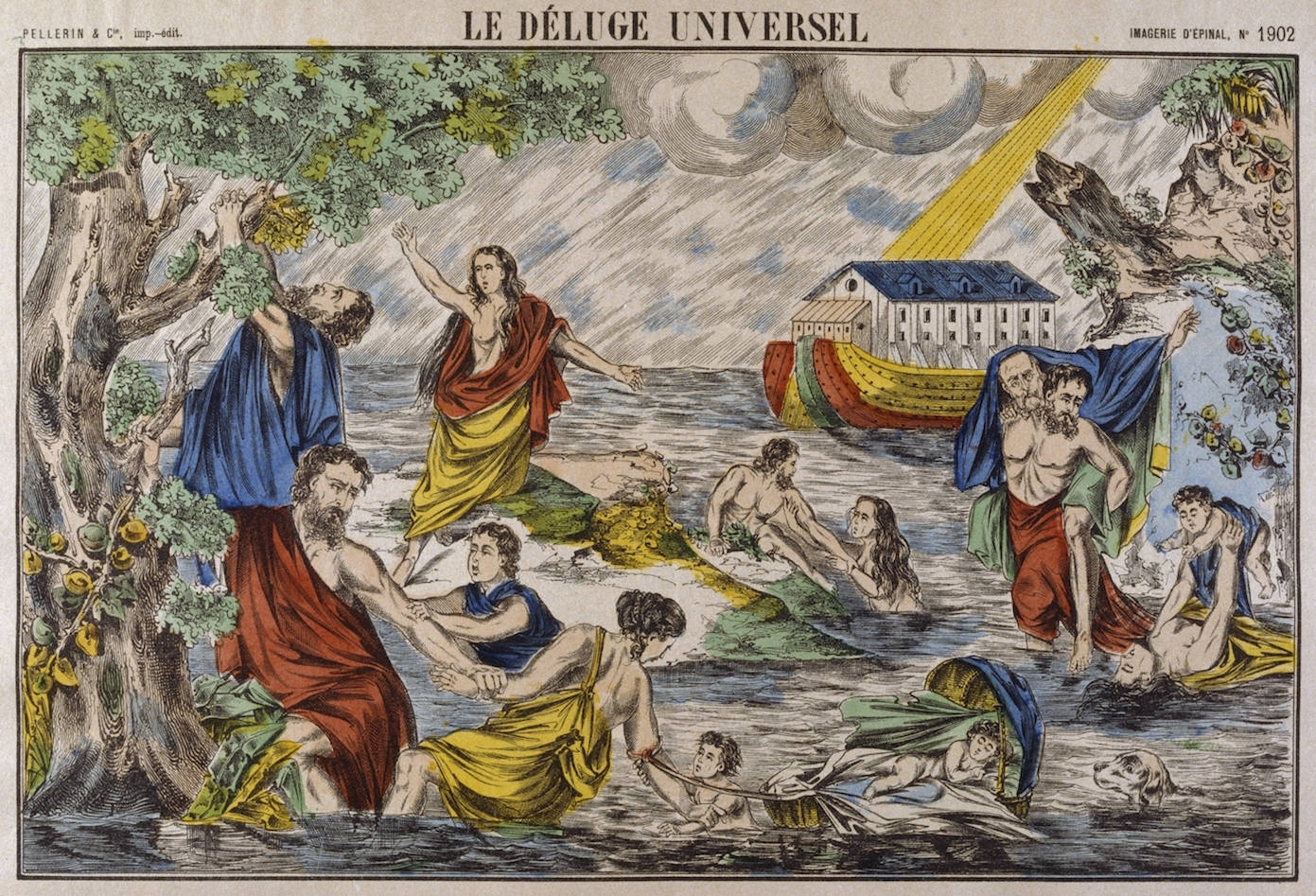

As readers, we are taught to value subtlety. We tend to be impressed by stories that tuck their deeper meanings into metaphor and image, rewarding careful attention; we wait for third-act reversals and thrill to inversions of well-trod story structure. There is an intolerance for fiction that insists on wearing meaning on its sleeve, let alone an overt moral. But, much like its namesake, there is no missing the allegory at the heart of Lydia Millet’s 2020 novel, A Children’s Bible. The story follows a group of children through the first days of a climate crisis, taking them through the Old and New Testaments in microcosm: a great flood, pestilence, a safe haven, a fatherless birth in a bleach-scrubbed stable. There are angels and saviors, converts and persecutors bereft of belief. The reality of these things is bleak—an escape to a seemingly idyllic farm inland goes disastrously wrong when the children are attacked by a band of militants; the bodies begin to pile up—and there is no happy (or holy) ending in sight. By taking her story back to one of the most enduring creation tales ever written, Millet’s novel functions as a warning and a gift. The coming apocalypse is an unsubtle thing, and by couching it in a familiar and well-trod structure, Millet invites us to grapple not with the intricacies of plot but with the very real grief over our own imminent loss—and, once the grief has subsided, to envision a world beyond the fall.

The novel opens on a modern child’s paradise, temporary though it may be: a sprawling vacation home packed to the brim with several families, the affluent parents wrapped up in their own intrigues and intoxicants, leaving the children to run free across the remote, seaside estate. The children at the heart of the story are living in a Swiss Family Robinson-meets-Wes Anderson pastiche of adventure games and precocious ennui. One child spends all her time scaling trees and buildings to improbable heights; others compare family real estate, or carry on minor romantic intrigues, or scheme to retrieve their confiscated electronics. The children’s lives are privileged, though existentially dissatisfying. They disdain their parents to the point of playacting severance, making a game of seeing how long each child can avoid having their parentage conclusively identified by the rest of the youthful crowd. As a result, the inhabitants of the vacation home are delineated cleanly into small opposing forces: the parents, reliably referred to en masse, and us, represented by Eve, who narrates the novel in first-person.

Eve, like her biblical predecessor, is burdened with knowledge: she is acutely aware of the fact that her life, and lives of those around her, are ultimately unsustainable. “At that time in my personal life,” she says, “I was coming to grips with the end of the world…Scientists said it was ending now, philosophers said it had always been ending. Historians said there’d been dark ages before . . . Politicians claimed everything would be fine…That was how we could tell it was serious. Because they were obviously lying.” Again like her biblical counterpart, Eve came to understand that what follows knowledge is pain.

Millet’s Eve is cursed with the psychological weight of parenting, if not childbirth: her chief preoccupation is with the well-being of her little brother, Jack, an odd and idealistic little boy with an impassioned love of the natural world. Their parents, like the others, are too drunk to be of any use, incapable of providing Jack with any real structure or support, and so Eve must step in to fill the void. Eve yearns to protect Jack’s innocence, but she understands this to be impossible. If Eve was unwittingly burdened with knowledge by her careless creators, she at least can pass that knowledge on to Jack with intention, love, and respect. She sits Jack down, in a sort of twenty-first century coming-of-age ceremony, to explain that his beloved penguins are doomed, a casualty of the collapsing climate. Like the parents, Eve fears the emotional impact of this news on Jack more than she seems to worry about the immediate impact of climate change on their lives, but, unlike their parents, Eve is certain that explaining reality to him is the right thing to do. “It was a Santa Claus situation,” she says. “One day he’d find out the truth. And if it didn’t come from me, I’d end up looking like a politician.” Jack’s lost innocence prompts the appearance of the titular Children’s Bible; it appears immediately after the penguin conversation and immediately before the storm that drives the children from their tenuous Eden.

The storm marks the beginning of complete climatic collapse, though ultimately this collapse is swift and merciless. The first days of the apocalypse are anticlimactic in a way that is both darkly funny and a cutting indictment of what brought us to the brink to begin with: the children cannot convince their ill-prepared and denial-drenched parents to leave the ruined house because the adults are too preoccupied with lease agreements, liability policies, and cash penalties to see the brutal reality before them. The children are eventually forced to choose their own safety, stealing a vehicle and striking out on their own. What follows is their harrowing attempt to survive the total implosion of civilization as they have known it. Emergency services vanish. Roads become impassable. The very wealthy have retreated to expensive, self-sufficient bunkers and compounds; everyone else, it seems, has been left to fend for themselves.

One could see another version of this story in which the children band together, forming a new society—a sort of cheerful reimagining of Lord of the Flies, the innocence of youth providing a clean new vision of the way forward, in which pluck and human ingenuity and love saves the day. But there is no pluck in Millet’s vision. Jack carries his Children’s Bible through a series of crises and traumas he should never have to witness, after receiving knowledge that never should have been his burden to bear. The novel’s fatherless birth in a stable ends in a woman bleeding to death for want of medical care; the deus ex machina that saves the children from an imminent threat is a vengeful, Old Testament savior figure, who dispassionately condemns those who crossed her to death in a fiery inferno. The “redneck” militia that attacks the children tortures and kills a scientist by tying him to a dogwood tree—the tree whose wood was supposed to have provided the wood for the Crucifixion—haloed by razor wire. The struggle for survival never becomes charming or even palatable. There is only the terrible slog of endurance, the acceptance of what cannot be changed, and the desperate struggle to take control of the very few things they can. Adults, those relics of the old world, are sometimes threatening, sometimes useful, but never a source of comfort, let alone wisdom. Most of them fall apart in the face of collapse; a few become monstrous. Blood is shed. Reprieve is temporary. The parents, those disinterested creators, may reappear, but they have learned no lessons and are no more fit to cope with the new world than they were to prevent its arrival.

The one glimmer of hope—or, at least, a glimpse of some kind of future—is in Jack’s singular reinterpretation of the simplified stories in his Children’s Bible. He grasps immediately that the book’s story is a metaphor (in a darkly funny moment, he gazes at a well-meaning adult for a long moment before telling her that the stories aren’t literally true, as if she were a dimwitted child); God is nature, he tells Eve, with all the gravity of a tiny prophet. Humans have misunderstood. Jesus is mankind’s comprehension of nature, as represented by scientific understanding. (It should give us all pause that science, by this interpretation, stands as a savior figure, offering humanity limitless promise before ultimately dying at the hands of our very human inability to heed its message.) The third part of the trinity, the Holy Ghost, however, is where Jacks’ interpretation struggles, and he spends the novel seeking to make sense of that mystery.

Like Jack’s experience with his Children’s Bible, I found Millet’s allegory overt—so overt it at first startled me. As a millennial, I’m constantly fighting against the irony-poisoned part of my brain that was conditioned by the late ’90s and early 2000s’ disdain for sincerity of any kind, and thus experience an instinctive resistance to a story that not only has an overt moral but is so unapologetic about what that moral is. Most of us know, at least loosely, the bible stories paralleled in the novel—Adam and Eve in Eden, the virgin birth, the Crucifixion—just as most of us are aware of the ways in which we are destroying the only home we have. The consequences of our actions are as scientifically predictable as they are existentially incomprehensible. We know what the end of the world will look like; it looks like A Children’s Bible. Bible stories are a way of making sense of the world, tales humans told themselves as a means of metabolizing their own place in the universe. A Children’s Bible, then, is a story we are telling ourselves as a means of metabolizing our role in our own downfall. A parable of the birth of humanity repurposed to tell the story of its end.

Such heavy-handedness can be a gift, in a way. There is no subtlety to the crisis we are living through, and there is no merit in pretending otherwise. That Jack receives a children’s bible serves as a callback to a time when children were shielded from the complications of reality, but it also allows Jack to comprehend the failures of the world he was given with searing precision. He knows—as all children know—that the choices being put before them are deeply wrong. Asked to sacrifice a small herd of goats to save human lives, Jack is bereft: “‘It’s not their fault,’ cried Jack. ‘We’re not supposed to sacrifice the animals. We’re supposed to save them. I’d rather sacrifice me.’” Nature is Jack’s God, and he would die to preserve its innocence. The progression of the story feels inevitable, the suffering richly rendered. And yet it is, as a reader, cathartic as well as painful.

This is what Millet offers: a chance to process the future now, before it is too late. By giving us a tale that conducts itself with all the tact of a hurricane, A Children’s Bible frees the reader from the work of tracing the parallels, leaving us to sit only with the emotional and intellectual impact of the story at hand. Eve and Jack’s crisis is our crisis, a catastrophe already well underway. To metabolize that truth is painful, and for now, such pain is easily sidestepped. We can busy ourselves with our day-to-day concerns, tell ourselves that it is not yet time to panic, reassure ourselves—as the children do, before the storm—with a certain cynicism, taking refuge in the fact that the end is uncertain and the causes beyond our control. And yet, like the children, we know we will not be able to sidestep the consequences forever. Millet’s novel calls on us, at least, to not be the them represented by the useless parents, or the blood-crazed militiamen, or the aloof and terrifying “Owner.” Instead, she offers the chance to be an us, to mine the remnants of the old world for what it can offer us—like Jack’s nascent reinterpretation of Christian dogma—and to, like Eve, protect our loved ones as best as we are able, without lying to ourselves about the crisis at hand. Jack must be told harsh truths, and he must be asked to make sacrifices, and he might not, in the end, be saved. But Jack can find solace, and beauty, and love, even at the end of all things. He can find his “Holy Ghost,” and hope within it. In A Children’s Bible, Millet invites the reader to let go of detachment and, like Eve, to see the world through Jack’s eyes, a world in which right and wrong are starkly rendered, and in which hope for humanity is found even in the ashes of its failures.

This piece was originally published on March 8, 2022.