Machine Language

1.

I recently spent a long weekend collaborating with friends on a narrative outline for a point-and-click adventure video game. Relying less on twitchy button-mashing and more on logic puzzles, conversation, and critical thinking, the adventure game genre is a good project for a writer, and I found it provided a whole new set of challenges that I had never encountered in fiction. How do you tell a story when the action is determined by the player? How do you write enough dialogue so that the player doesn’t read the same few lines too many times? How do you plant clues to an ending twist that can play out three different ways, depending on the player’s choices throughout the game?

It was the most satisfying weekend of writing I’d had in months, and when the project stalled because we couldn’t align our schedules, I decided I’d start work on a solo project and teach myself how to write—and code—a video game.

2.

A year ago I read Vikram Chandra’s wonderful book Geek Sublime, a meditation on coding, language, and the experience of beauty. Coders, Chandra points out, are as obsessed with elegance and style as any literary writer. Early in the book, he cites the programmer and venture capitalist Paul Graham, who, in his essay “Hackers and Painters,” writes:

[O]f all the different types of people I’ve known, hackers and painters are the most alike. What hackers and painters have in common is that they’re both makers. Along with composers, architects, and writers, what hackers and painters are trying to do is make good things.

3.

I decided to pick something simple, to match my lack of skill. A platform in the vein of Super Mario Brothers or Metroid, classic Nintendo games I had loved growing up. I would make it in GameMaker, an engine I picked because it was free and used a scripting language that was easy enough for newcomers but robust enough to serve as a primer for more complex programming languages like C#.

I began with a concept and roughed out an outline, as I had when collaborating with my friends on the adventure game. When I started trying to code it, however, I sank immediately into a swamp of technical particulars. Doing something as simple as moving a character across a screen and jumping at the press of a button required no fewer than seven finely tuned variables and a dozen or so lines of code—inscrutable clumps of variable names and “if”s and mathematical symbols and curly brackets. It was as if I had started a novel only to realize I would need to spend hours and hours of work writing the rules of grammar, down to the simplest construction.

Still, it gave me the same satisfaction of writing. It was sticking your fingers into imagination and shaping something until I had a thing.

4.

From Gerald Jay Sussman and Hal Abelson’s 1979 textbook Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs:

“Programs should be written for people to read, and only incidentally for machines to execute.”

5.

In coding, the medium and the effect feel very different. Mario’s jump is made out of numbers and equations. It probably looks like a bunch of “x”s and pluses and gnomic commands, and it probably took a coder or days or weeks of tinkering to get it just right. But reducing it to just a bunch of numbers is like reducing a poem to just a bunch of letters. In Mario, as in poetry, it’s about how it makes you feel—the spring, the loft, the freedom of movement and strictures of momentum. It feels natural, a foregone conclusion, just the way a great poem or short story feels like it couldn’t possibly be done any other way.

Video game design—which as a field is far behind the liberal arts in finding ways to discuss the ineluctable—call this “game feel.”

6.

From Chandra’s Geek Sublime:

Most of the artists I know—painters, filmmakers, actors, poets—seem to regard programming as an esoteric scientific discipline. . . . Many programmers, on the other hand, regard themselves as artists. Since programmers create complex objects, and care not just about function but also about beauty.

7.

One notable difference: code usually tells you immediately when something isn’t working. I changed one variable that caused the character to float up and off the screen when I pressed the jump button—then I went back and looked at the code, figured out what I did wrong, and fixed it.

I’ve gone months, sometimes years without knowing how broken a short story is, and even with the help of a sharp reader or editor, it can be hard to see. Code runs on logic, but logic can only take fiction so far.

8.

In an interview that appeared in the New Yorker, Tom Bissell, a literary fiction writer who now works in video games, described working on a large video game team as “invigorating, and fascinating.” I’m finding it the same. It’s a fascinating trip into a technical art form. It’s a new syntax and grammar to grapple with. It’s another way of making.

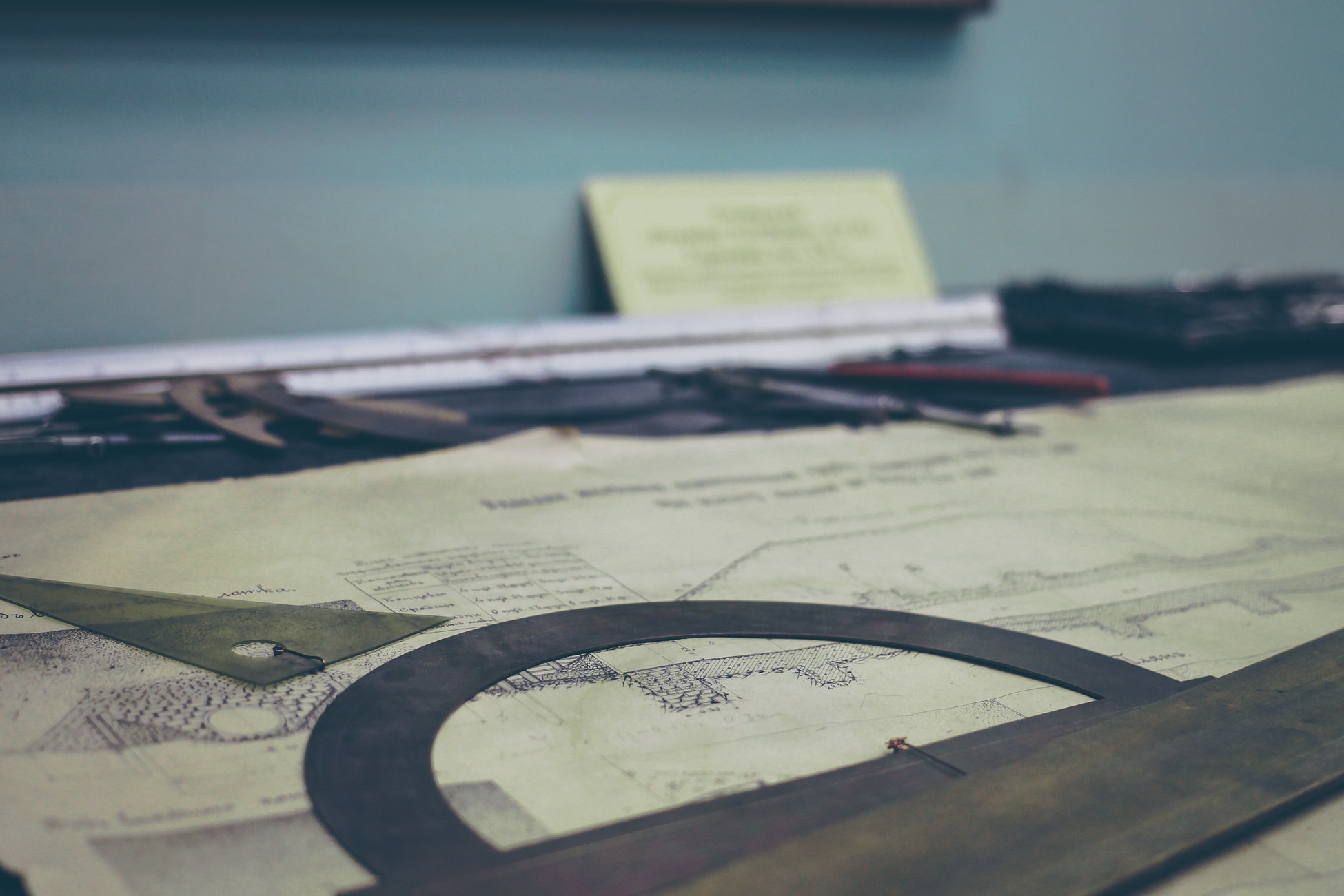

Image: Excerpt of Ben Fry’s distellamap of Pac-Man for the Atari 2600. The text is the assembly code that runs Pac-Man. The lines are the logical relationships between different pieces of code.