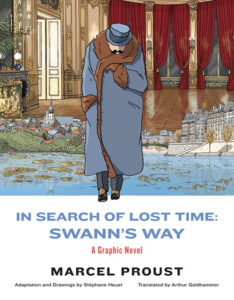

Review: Marcel Proust’s IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME: SWANN’S WAY – A Graphic Novel by Stéphane Heuet

IN SEARCH OF LOST TIME: SWANN’S WAY by Marcel Proust

Adaptation & Drawings by Stéphane Heuet

Translated by Arthur Goldhammer

Liveright, English reprint ed. July 2015

240 pp, $26.95

There are few challenges as alluringly counterintuitive as adapting Proust; attempts to do so have produced wildly varying results in a surprising array of forms (heck, there’s even a musical). Much like Proust, comics are a big deal in France (sometimes referred to there as ‘the 9th art’) and a graphic adaptation was, perhaps, inevitable. Whereas literary comic book adaptations tend to be treated with critical indifference in the English speaking world, Stéphane Heuet’s In Search of Lost Time was deemed serious enough to provoke outrage in France: Le Figaro, the popular daily that Proust himself once wrote for, reviewed the first part of the comic under the title ‘It Is Marcel Who Is Assassinated’ – this did not stop it becoming a surprise bestseller.

Heuet’s comic is now available collected and with a new English translation. That it was originally published episodically is significant, as Heuet’s ability improves considerably as the book progresses. The first section of the comic demonstrates its biggest shortcomings: attempts to render thought through visual metaphor feel mechanical (logical in intent; pedestrian in execution) and the sheer volume of text is near suffocating. The book’s blurb describes it as a ‘perfect introduction to’ In Search of Lost Time, but much of the pleasure culled from the book’s opening stems from academic comparison.

Through contrast, the claustrophobic intensity of these early sections turn the famous madeleine moment into a near revelation: pages and pages of text filled panels lead to a double page spread of Combray and the locations yet to be visited.

Heuet hits his stride when reaching the near self-contained ‘Swann in Love’ novella. Proust himself is an author to savour; Heuet’s ‘Swann in Love’ is a compulsive read. Much as a couple may argue over a reproduction masterpiece clashing with the drapes but stand in awe of the original, so Proust, partly relieved of his immense reputation, is highlighted through reconfiguration as a lyrically caustic humourist and, perhaps surprisingly, an excellent plotter: the narrative mirroring lurking behind the ebb and flow of his prose now being at the fore.

Visually, Heuet posits himself within the Franco-Belgian ligne claire tradition, alternating between hints of realism and caricature: Dr Cottard, of Madame Verdurin’s little circle, is almost a bourgeois Captain Haddock, and the face of young Marcel resembles Tintin himself. Heuet cleverly evokes nostalgia through his illustrations, utilizing a style many encounter in childhood. Frustratingly, his fidelity to the source material almost restrains the potential hinted at by the comic medium; if, as Art Spiegleman says, ‘comics are time turned into space,’ what formal potential there is in adapting the great novel on time… Despite all the reservations mentioned, however, the comic succeeds at what all literary adaptations strive: it illuminates aspects of a work it can never hope to replace. The book is charming and thoroughly enjoyable, qualities which Proust’s work possesses but are often forgotten.

***

James Reith is a writer, musician and Proust enthusiast currently residing in High peak, England. You can bother him on twitter @James_Reith.