Mistresses, Written by Women

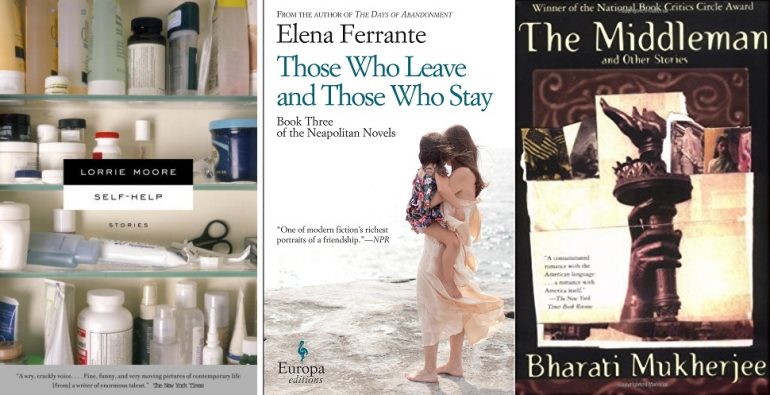

The affair in Lorrie Moore’s story, “How to Be an Other Woman,” starts with a meet cute on a bus: “A minute goes by and he asks what you’re reading. It is Madame Bovary in a Doris Day biography jacket.” It’s a clever description of the story itself, which like many of the stories in the collection, Self-Help, is written in the second person. It’s considerably more playful than Madame Bovary and doesn’t end in suicide, but gives serious consideration to the trials of adultery. Unlike Flaubert’s protagonist, Moore’s is not married. She finds out after the affair is already underway that her lover is married. She’s been duped into mistress-hood.

When you were six you thought mistress meant to put your shoes on the wrong feet. Now you are older and know it can mean many things, but essentially it means to put your shoes on the wrong feet.

You walk differently. In store windows you don’t recognize yourself; you are another woman, some crazy interior display lady in glasses stumbling frantic and preoccupied through the mannequins. In public restrooms you sit dangerously flat against the toilet seat, a strange flesh sundae of despair and exhilaration, murmuring into your bluing thighs: ‘Hello, I’m Charlene. I’m a mistress.’

The final indignity—the punch line—is that her lover is not even married. He’s divorced and cheating on the woman he lives with.

In Bharati Mukherjee’s story, “Jasmine,” from The Middleman and Other Stories, the title character has immigrated illegally to the United States from Trinidad. Jasmine moves quickly from unpaid work at a motel in Detroit to a nanny job for a family in Ann Arbor, which she’s identified as a city of opportunity. She learns of the job through the University of Michigan’s student employment office, though she’s not a student. The father of the child she takes care of is a professor and the mother is a performance artist.

She can’t believe her luck at landing the job, but fears about her immigration status are threaded through the story. “She thought Bill Moffitt was going to ask her about her visa or her green card number and social security. But all Bill did was smile and smile at her—he had a wide, pink, baby face—and play with a button on his corduroy jacket.” After two months, the couple figures out she’s not a student, “but they didn’t care and said they wouldn’t report her. They never asked if she was illegal on top of it.”

When Bill’s wife goes on the road with her performance group, Bill, of course, seduces Jasmine, who has been thinking about him, though she knows it’s “stupid and sinful.” It’s easy to see why she thinks about Bill. She lives in his home and interacts with few people outside his family.

She felt so good she was dizzy. She’d never felt this good on the island where men did this all the time, and girls went along with it always for favors. You couldn’t feel really good in a nothing place. She was thinking this as they made love on the Turkish carpet in front of the fire: she was a bright, pretty girl with no visa, no papers, and no birth certificate. No nothing other than what she wanted to invent and tell. She was a girl rushing wildly into the future.

His hand moved up her throat and forced her lips apart and it felt so good, so right, that she forgot all the dreariness of her new life and gave herself up to it.

The story ends there, in Jasmine’s moment of triumph, but Mukherjee has provided enough details of her tenuous position that the rest can unfold in the reader’s mind: the return of Bill’s wife, her discovery of the affair, how easy it will be for the couple to dispense with Jasmine when the time comes. This kind of ending seems inevitable, but it’s not written down. It could be different—and that’s the captivating thing about Mukherjee’s restraint.

The narrator of Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan Novels, Elena Greco, seems to have more power than Jasmine. She is a successful author married to a professor when she begins her affair with a married man, Nino. At first Elena and Nino, trying to hide the affair from their spouses, are on equal footing:

He began to call obsessively. I loved those phone calls, especially when we said goodbye and I had no idea when we would talk again, but then he called back half and hour later, sometimes even ten minutes later, and began to rave, he asked if I had made love with Pietro since we had been together, I said no, he made me swear, I swore, I asked if he had made love to his wife, he shouted no . . .

But Elena quickly tells her husband the truth and separates from him. Nino promises he’ll leave his wife, but finally tells Elena he can’t. Elena perceives her position immediately: “So if I understand you: you are proposing, as if it were a reasonable solution, that I abandon the role of lover and accept that of parallel wife.” She has quickly become the mistress, much more available to Nino than he is to her.

She becomes pregnant, and although Nino is happy with the news and promises to give the baby his name, she still recognizes the inequality in their situation: “. . . I left my husband, I came to live in Naples, I changed my life from top to bottom. You instead still have yours, and it’s intact.” She throws him out but always takes him back. “At those moments I saw myself suddenly for what I was: a slave, willing to always do what he wanted . . .”

Moore and Ferrante are vastly different stylists, but the mistresses in both of their stories wait up nights for men who do not show up, and they reach similar conclusions about themselves. Moore’s Charlene makes lists, often in the language of self-help:

1. Fallen in love(?) Out of control. Who is this? Who am I? And who is this wife with the skis and the nostrils and the Tylenol and does she have orgasms?

2. Reclaim yourself. Pieces have fluttered away.

3. Everything you do is a masochistic act. Why?

4. Don’t you like yourself? Don’t you deserve better than all of this?

Ferrante’s Elena wonders if she’s a fraud.

Was I lying to myself when I portrayed myself as free and autonomous? And was I lying to my audience when I played the part of someone who, with her two small books, had sought to help every woman confess what she couldn’t say to herself? . . . In spite of all the talk was I letting myself be invented by a man to the point where his needs were imposed on mine and those of my daughters? . . .

. . . I learned to avoid myself.

Eventually Nino betrays and humiliates her so severely that she does leave him, but it takes years. Jasmine, just beginning her affair at the conclusion of the story, is in a different state of mind. She believes it’s possible to reinvent herself in her new country, inspired partly by Bill’s wife, the performance artist, who is given to saying, “I am my own person.”

She feels free and autonomous (to borrow Elena’s language), but she doesn’t yet see that she’s also being invented by Bill. “You are your own person now,” he says, giving her the small choice of which record to play when he’s already turned off the lights, made a fire, and told her they’re going to dance.

“You’re a blossom, a flower,” he tells her as he’s trying to undress her. “You’re really something, flower of Trinidad,” he says once she’s naked.

She corrects him: “Flower of Ann Arbor.”

The distinction matters a great deal to Jasmine, but Bill doesn’t acknowledge it. She’s agreed to be the flower.