More Known Things

About a week ago, Fireside Fiction released a report detailing the state of black writers in speculative fiction. As one of its compilers, Cecily Kane called her catalyst deceptive—while perusing anthologies and journals and bio-pages, she found herself surprised by their diversity. But then she took another look. Underneath those numbers she found some glaring omissions: there wasn’t simply an absence of black writers—specifically—in the publications she’d found, most institutions were entirely bereft.

In the report itself, Kane detailed her findings:

“Out of 2,039 original stories published in 63 magazines in 2015, only 38 stories could be found that were written by black authors… That’s just under 2%. The median number of stories by black authors in these magazines is zero, which means that more than half of all speculative fiction publications measured did not publish a single original story by a black author in the year of 2015.”

These are not impressive numbers. But they aren’t entirely surprising either. Since its integration into American culture at large, with the emergence of Robert E. Howard and H.P. Lovecraft and Hugo Gernsback, speculative fiction has always been willfully short-sighted in regards to race. There are outcries when staples of an otherwise white canon are replaced by heroes with more melanin. Black sci-fi protagonists are far and few between. And whenever a black sci-fi author does manage to plow through the fold, they are deemed as The One, as evidence of affirmative action at work, and conversations surrounding the lack of diversity promptly end.

Later on in the same report, Brian White mirrors those notions:

“We all know this. We do. We don’t need numbers to see that, like everywhere in our society, marginalization of black people is still a huge problem in publishing … The entire system is built to benefit whiteness – and to ignore that is to bury your head in the flaming garbage heap of history.”

And later on, in a conversation with The Guardian, White elaborated on that notion:

“I think that anyone who is paying attention to the demographics of speculative fiction publishing in general, and short fiction in particular, knows that there is a problem with underrepresentation of people of color, and that it is even worse for black writers.”

White acknowledged that sci-fi’s overall diversity is improving. Slowly, but surely. And of course this is a good thing. But he continued by noting that progress in overall diversity, when it does occur, has a hand in hiding the problem “because publishers can point to and feel good about ‘look at all the people of colour we have featured’ without examining it more closely to see who is still excluded.”

Genre aside, this aversion to blackness is an ongoing problem in supposedly “literary fiction,” too. In some circles, race isn’t even worth attempting to put on the page unless you have a stable of black friends on speed-dial. But if this is an issue that is accentuated on the literary end (in an interview with the Paris Review, Mitchell S. Jackson noted that “if I was part of the establishment and I was trying to maintain some kind of hold on it, I wouldn’t allow that many people through either”), perhaps it is accentuated within speculative-fiction—it is hard enough to gain acceptance when many authors don’t even know that the opportunity’s open to them.

Some might look at this sentiment and claim it’s a call for publishers to seek out black authors for the sake of their being black. It isn’t (at least not this time). But when, as per the report, “the probability that it is random chance that only 1.96% of published writers are black in a country where 13.2% of the population is black is 0.00000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000000321%” the effort simply isn’t being made. You really aren’t trying at all.

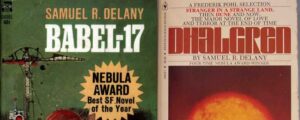

In a 1998 piece for the New York Review of Science-Fiction, Samuel Delany spoke on racism within the science fiction community at-length. Even as a guy who’d won countless awards, who’d been acknowledged as one of the most enchanting practitioners of his craft, he was castigated by many of his peers, taken for a token, and once, in a meeting with Isaac Asimov, following Delany’s receipt of the 1968 Nebula Award, Asimov reminded him that “You know, chip, we only voted you those awards because you’re a Negro…!”

But Delany continues:

“Well, then, how does one combat racism in science fiction, even in such a nascent form as it might be fibrillating, here and there. The best way is to build a certain social vigilance into the system… because we still live in a racist society, the only way to combat it in any systematic way is to establish—and repeatedly revamp—anti-racist institutions and traditions.”

It would be presumptive to assume that Fireside’s report will change anything in the immediate-term. For a lot of us, it’s just confirmation. But the statistics shouldn’t be the grounds for a lack of hope, or the possibility of what can (continue) to be achieved. In his introduction to The Best American Science Fiction and Fantasy 2015, Joe Hill notes that:

“This is the truth of science fiction and fantasy: it is the greatest fireworks show in literature, and your own imagination is a sky waiting to catch fire.”

If we wanted a bigger show, allowing more participants into the fold, and showing them that they have a role within it, wouldn’t be a bad idea. But maybe it’s less of a lack of an imagination that we’re tentative of, than apprehension of what it might bring.