Netflix’s ANNE Bridges the Divide Between Us and Our Childhood Dreams

I grew up reading L.M. Montgomery’s Anne series; the books were dearly treasured companions of my childhood. With their passages of sometimes exquisite poetry, especially in describing the natural world, they nurtured my love of writing and my reverence for words, especially the big ones Anne declares necessary to describe big ideas. The ways in which Anne, the mercurial, earnest girl at the center of the story lived, learned, grew, and blundered her way through life resonated with me, a perennial outsider and dreamer, wounded by things that, like Anne’s cruel treatment at the hands of the Hammonds and the orphanage asylum, lurked in the corners of things—never forgotten, but making the joys of a safe refuge all the more poignant, warm, and vital.

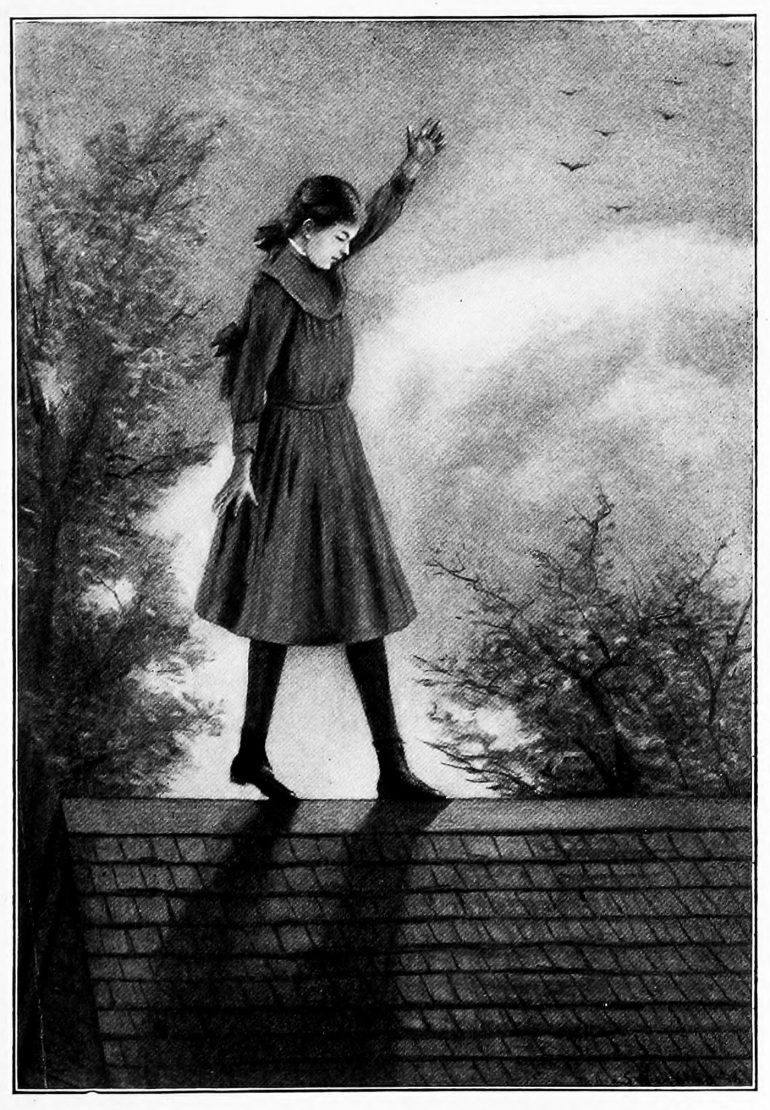

There are certainly purists who went into full-blown rages when it was announced that Montgomery’s books were going to be adapted, once again, into a television series. Fans of the beloved 1985 series were particularly concerned. Whether encountered through the numerous adaptations for television and film, or through the books themselves, the fiery, dreaming, and plucky orphan girl and the refuge she finds in the town of Avonlea form a central and cherished part of so many childhoods. This new series, written and produced for Netflix (and available for streaming on May 12) by Emmy award-winning Moira Walley-Beckett of Breaking Bad fame and starring Amybeth McNulty as Anne, takes the original story into searing new emotional territory. It has been described as much darker than the original books and series, and is a wonderfully and overtly feminist take on the original story, but what I find most compelling is how much it unearths from what was already under the surface of the classic books.

I read the books again and again, the first one almost annually. And even now, as a married, adult woman, I return to them, especially in times of anxiety and depression. Lately, I’ve been wondering about what draws me to them again and again, the things that are at the corners and under the surface of what is told and what isn’t. And the absolute certainty of Anne being a “kindred spirit,” all “spirit and fire and dew” as she is, despite, and in some ways because, of all she’s been through. I’ll even admit here that, growing up, and in particularly difficult times, I’d talk to her in my head, not unlike the way she talks to Katie Maurice in the glass of the Hammonds’ cabinet, and in the new series, again in the glass of the Cuthberts’ clock. I wanted to know what she thought, what she might think of me. I wanted to know that, as someone who also went through devastating trauma in the early parts of her life, as someone who clung to dreams and books and the natural world because her life and heart depended on them, she understood.

This new series opens with eerie and magnificent art crafted by creative director Alan Williams and artist Brad Kunkle, with gilded and dappled melding of the natural world of leaves, birds, insects, and animals and the figure of McNulty as Anne herself, with flowing copper hair and almost pre-Raphaelite gestures and spirituality. It cuts between the sometimes frantic eloquence and enthusiasm of its main character to flashbacks of the brutality she has suffered at the hands of foster families and bullies her own age.

The cinematography is artistically stunning, playing with light, gesture, and close-ups on the expressions of the brilliant main cast to compelling effect. All of these elements pick up on some of the most enduring and compelling qualities of the original work: its immense sensitivity, its vivid poetry, and exquisite attention paid to both the wonder and solace of the natural world, and the fraught world of human relationship.

The show is, however, by no means an easy watch. The Hammonds’ cruelty to Anne, and even the relationship between Prissy Andrews and the schoolteacher Mr. Phillips, dismissed in the books as something “of the time,” are here shown as more sinister, cruel imbalances of power, which is, perhaps, what they always were. Anne repeats stories of Mr. Hammonds’ cruelty with the macabre enthusiasm of a child trying to impress her schoolmates, unaware of the full implication of what she says, and is ostracised for it, even called “filthy” and “tarnished.”

Her past is something that marks her in the present, setting her heartbreakingly apart from other children. While the books were far gentler in their treatment of her past and its effect on the present Anne, who finally has the relative safety to grow and flourish, the series is uncompromisingly realistic in how that would play out. Anne is ridiculed and judged for her background and the things she’s been through, and her journey towards acceptance by others is a back-and-forth, fraught, and difficult process, as it would be in life.

The dream world Anne creates, so charmingly rendered, and sometimes fairly tongue-in-cheek in the original, loses none of its potency here, but is shaped in direct relation to the psychological wounds of her neglect and ill-treatment by others in the past. It takes her reveries and streams of chatter from the childishly charming or grating to what they largely are in reality: refuges, pleas for love and regard, displays of a spirit that is, miraculously and wondrously, unbroken by cruelty and neglect. Painted with a lighter hand in the book, the series, with its earnest, vivid acting by McNulty and the artistic brilliance of its direction, heightens these tensions to reveal new depths and unearth some of the things that perhaps made the books so subconsciously compelling.

The brightness of the books is not lost, either. The White Way of Delight is shown with a reverence and beauty that is visually breathtaking, as it ought to be, and so are the Lake of Shining Waters and the magnificent Snow Queen. The visuals of the film paint in vivid color the beauty Anne is so utterly attuned to, and our imaginations are given ample cues to follow her reveries.

The same is true for the relationship between Anne and the Cuthberts, played with staggering skill and sensitivity by Geraldine James and R.H. Thomson. Trust is built slowly, tempers flare, and the earnest reaching of each to the other is realized in poignant and moving moments, from the first time Matthew calls Anne his daughter to a stranger, to Anne running to seek refuge in Marilla’s arms after being ridiculed at school. The relationships are searingly human, and show all the hesitations, triumphs, and love of building a family.

The friendship between Anne and Diana, played by Dalila Bela, is also explored wonderfully, as Anne fights earnestly for acceptance among the other children, and Diana comes to genuinely see and value Anne for the person she is. Whether they are making their solemn vow to be bosom friends for all time, or accidentally getting raucously tipsy on currant wine (my favorite moment in their friendship so far, and deviating from the books in that they both drink, to hilarious effect), the camaraderie, solace, and depth of friendship among women is explored in a way that is wonderfully affirming.

The same, so far, is true for the other crucial relationships in the series, including that between Anne and Gilbert, played wonderfully by Lucas Jade Zumann, who brings the charm and understated gallantry of Gilbert’s character to life. The cruelties children enact on each other, as well as the ways in which they strive for friendship and understanding, are played out in a way that heightens the original conflicts of the books and explores them with earnest humor and pathos.

All of these elements so far have brought to life the very real ways in which outsiders of any kind seek acceptance and kindness, the ways in which trauma lingers and manifests, and the solace we find in each other, in the natural world, and the worlds of books and dreams. These things have always been present in the original books, but the deftness and virtuosity of this series’ realization of these themes takes them to new and moving depths.

The world of Avonlea has been frequently painted as idyllic, the books charming childhood relics, existing in a space and time outside of the darkness that besets our “real” world. Reading them as a traumatized child, I sometimes felt removed from its essential wholesomeness, I felt unable to reach Anne even as her character and spirit connected with me. The silences that are still in the corners of the books, silences about what neglect, bullying, and abuse do, the very real forms they take, made it sometimes difficult to articulate just what was so compelling in the beautifully and charmingly drawn world of Avonlea, with all its “tempests in the school teapot,” its earnest beauty, and lasting place in so many people’s hearts.

This series has had the grace, so far, to bring those two things together, showing us that it’s only in contrast to the dark that the light, the delightful, the joyous, the loving, are seen in their full splendor. It doesn’t leave us, the wounded adults and scarred children, behind. In many ways, it is, at last, the real, living girl, Anne, who has seen and been subjected to terrible things, reaching through to us to bring us into the flawed but beautiful haven she found when the Cuthberts adopted her. It’s still a fraught place, of course, but it gives her room at last to breathe, to be a child, to struggle and love and delight in the world, and in growing up. In Anne, we realize at last that we’re not too tarnished for her glimmering dreamscapes, the wholesomeness of the books’ earnest morality. We are all, wounded as we are, quite like our heroine. We always have been.