NOTES ON THE STATE OF VIRGINIA: Journey to the Center of an American Document, Query XXIII

This is the final installment of a year-long journey through Thomas Jefferson’s Notes on the State of Virginia.

Query XXIII: The histories of the state, the memorials published in its name in the time of its being a colony, and the pamphlets relating to its interior or exterior affairs present or ancient.

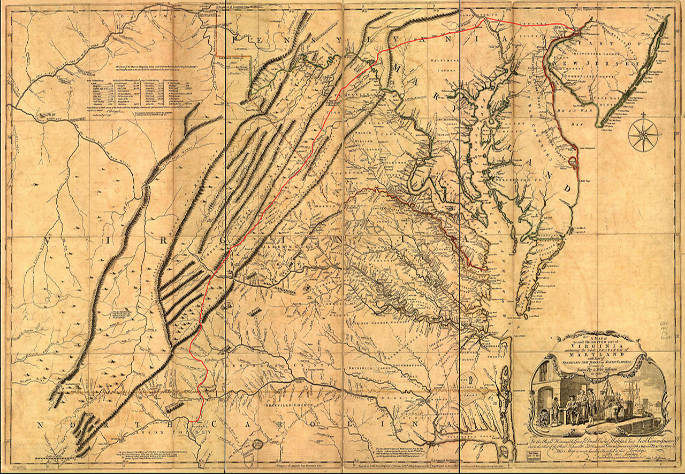

Now that we’ve reached the end of Jefferson’s contemplation of Virginia, it seems like a good time to recall how all this began. Ever the methodical draftsman, Jefferson starts by following the lines a previous cartographer—his father—first drew in 1753. On that survey map, Peter Jefferson frames the Commonwealth in narrow bands of ink to demarcate its physical boundaries. Some thirty years later, Thomas Jefferson’s own lines in Notes on the State of Virginia gather symbolic richness. They diverge into the river systems that enable life and commerce; they soar to trace the heights of Natural Bridge and other geographical wonders; and they forge themselves into the building blocks of governmental institutions and public universities before settling, as arithmetic sums, into the ledger books of American farmers, merchants, and bankers.

As a poet, I’ve loved following Jefferson’s vibrant lines and thinking about how his rhetorical strategies may connect (at times directly, at others tangentially) to the techniques of verse. Though Notes was not produced as a work of poetry, the text nonetheless delivers an immersive experience in language, a goal that contemporary poetry shares. To read Notes in 2016 is to trace Jefferson’s vision for New World democracy, a vision articulated in expansive, searching prose. In reading this series, I hope you’ve rediscovered some of the dynamism of Jefferson’s language, its frankness, wit, and systematic attention to form, which reveal much about what Jefferson wanted America to be, and to mean. Open the treatise to any page, and that verbal energy is still palpable. Jefferson is always on the move.

Even so, Query XXIII is about setting things down for posterity. In this section, Jefferson lists more than two hundred and fifty texts that preserve a collective account of early Virginia. He cites published volumes by colonial-era personalities like explorer John Smith, Henrico Parish rector William Stith, and the wealthy central Virginian planter Robert Beverley, among others. Additional documents, which Jefferson calls “state-papers,” consist of written treaties, royal grants, deeds, charters, proclamations, and legislative acts encompassing Virginia’s history from 1496 through the Declaration of Independence, which Jefferson himself authored in 1776. Though Jefferson says his catalogue is “far from being complete or correct,” this part of Notes presents an impressive compendium of historical, legal, and political language that details the character of the Commonwealth.

But Jefferson is right about Query XXIII, though not for the reasons he anticipates. His account of Virginia can’t be complete without the voices of all the people whose experiences contributed to its complex history. To read Jefferson’s catalogue, you’d think the Commonwealth consisted only of aristocrats, planters, clergy, pamphleteers, and military men. Jefferson cites no letters written to or from women, no writings by tradespeople or subsistence laborers, and certainly no histories of the numerous Native American cultural groups who inhabited the region before, during, and after colonization.

The experiences of the enslaved are missing, too. In Jefferson’s time, Virginia planters often actively prohibited their slaves from attaining literacy (the Commonwealth would, in the nineteenth century, explicitly criminalize teaching slaves to read and write). Literacy in the enslaved was perceived as a threat to the continuation of the chattel system on which the Commonwealth’s economy depended. Fully understanding how the men of Jefferson’s sphere narrated Virginia’s history means coming to terms with a major truth: in controlling the literacy of others, they achieved control over the narrative.

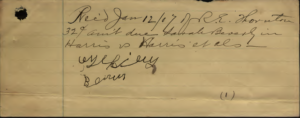

Which brings me to the “memorial” of Virginia that means the most to me: a tiny slip of paper signed by my great-great-grandfather, Ezekiel Beverly.

Born around 1839, Ezekiel lived in Fairfax County, Virginia, about one hundred miles northeast of Monticello. While I’m not sure whether his surname, “Beverly,” indicates a direct connection to the wealthy white “Beverley” family whose patriarch penned one of the first histories of the Commonwealth, I can say that Ezekiel’s roots in the Piedmont region of Virginia ran deep. His father, Harrison Beverly, was born in Prince William County in 1800, the same year that Jefferson assumed the Presidency. Right now, I’m trying to find out more about Harrison and Ezekiel’s births; who owned them? Where?

Post-Civil War census records for Harrison and Ezekiel indicate that neither knew how to read or write. If they had been born into slavery, they would have had no opportunity for formal schooling. Eventually, Ezekiel became a successful farmer in Fairfax County. And in 1907, while in his late sixties, he signed a receipt for $0.32 as part of a chancery case. In those jagged, halting lines is the origin of my family’s journey from slavery and into true freedom. Ezekiel is the first member of my African American family to leave evidence of his own literacy. When I look at his signature, I feel sadness and joy, a combination which, for poets, adds up to wonder.

And wonder is the place where poetry begins.