Obama the Ellisonian: Another Reading of the President’s Worldview

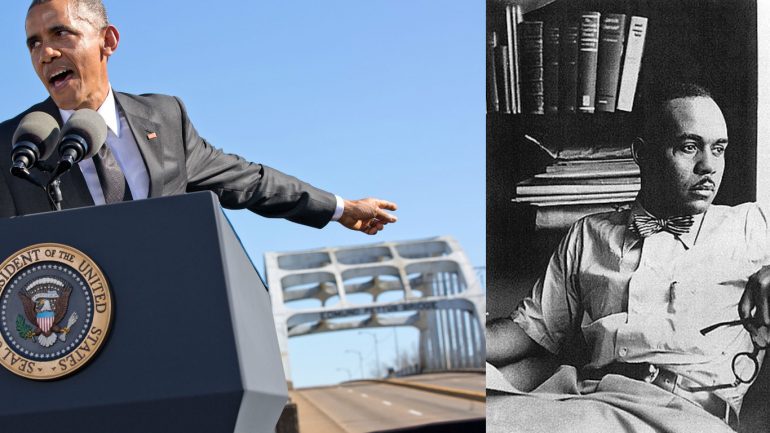

Early in the speech that Barack Obama gave last year to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of “Bloody Sunday,” standing in front of the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Alabama, the president asked, “What can be more American than what happened in this place?”

That line deserved more attention than it got. To recap what happened there: a large group of unarmed, peaceful protesters walking from Selma to Birmingham to demonstrate for voting rights for all citizens attempted to cross a bridge named for a Confederate general and early leader of the Ku Klux Klan. While crossing, they were ambushed by a force of state troopers who, first, refused them passage and then, when the protesters didn’t yield, chased them back and attacked them with fists, billy clubs, and tear gas. It was a moment when all of America’s history, tradition, and institutional authority seemed to coalesce violently to beat back a fragile movement toward racial justice.

What does it mean to characterize that as the essential American moment? And to do it in a speech described as optimistic? And if you do that, how can you also be criticized for your romantic view of American history, and for your refusal to “accept that plunder and bigotry are part of America’s foundation?”

Jeffrey Goldberg’s profile of the president in the April Atlantic highlights the same paradox. Obama is an optimist, Goldberg concludes, but a Hobbesian one. Goldberg writes:

He has a tragic realist’s understanding of sin, cowardice, and corruption, and Hobbesian appreciation of how fear shapes human behavior. And yet he consistently, and with apparent sincerity, professes optimism that the world is bending toward justice.

For Goldberg, this is a contradiction.

But it might be more helpful to think of it as a mystery, in the sense that Flannery O’Connor used the word. How can bad actors, shaped by fear, build a better world? How can the weak overcome the powerful? How can victory come from defeat? For O’Connor, mystery was the province of the novelist, and I think that gets to the heart of it: if you want to understand Obama’s way of thinking, it helps to be the kind of person who’s at home in the messy, heteroglossic, meaningful world of novel-reading.

Specifically, it helps to be the kind of person who’s at home in the novel that Obama is said to have read and re-read as a college student: Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man. I watched Obama’s speech a few hours after he gave it, not long after I had finished the last chapter of my dissertation, a chapter that happened to be about Ellison. That was a strange experience: submitting my dissertation, I thought I was done for at least a few hours with the world of Ellison; I thought I could escape for a little while into the outside world, to see what was going on in politics and contemporary culture. Instead, turning on the TV that afternoon, I found myself right back in Ellison’s worldview.

In particular, I saw Obama echoing Ellison’s idea of the uses of defeat, an idea reflecting the jazz concept of woodshedding. In popular parlance, a “woodshedding” means a terrible defeat: if a football team loses embarrassingly, they’ve been taken to the woodshed. But in the jazz world that shaped Ellison, “woodshedding” was what happened after a bad show, in the solitude where an embarrassed musician nursed his wounds and honed his chops in preparation for the next performance. Writing about jazz in many of his essays, Ellison regularly referenced moments when defeat becomes redemption, like when Eddie “Lockjaw” Davis “underwent an ordeal of jeering rejection until finally he came through as an admired tenor man.”

University of Delaware professor A. Timothy Spaulding sees “woodshedding” as the operating dynamic of Invisible Man—the novel’s narrator writes his narrative from an underground room where he has been forced to take refuge after a series of defeats, culminating in the aftermath of the carnivalesque riot of the novel’s last chapter. Nonetheless, the narrator writes, “I must come out, I must emerge,” and that emergence is the narrative itself, which Spaulding says synthesizes the chaos that has characterized the events of the novel. From this view, it’s a mistake to see any defeat—or any victory, for that matter—as final. This complicates a classic text of the Obama era: David Samuels’ 2008 essay comparing Obama to Ellison’s narrator. At one point in that piece, Samuels suggests that Obama put a happy ending on a tragic novel. Now, after eight years of rancor, in a moment when Donald Trump will be the Republican Party’s nominee for president, it’s hard to see Obama’s electoral win as a happy ending. In the context of Obama’s Ellisonian worldview, though, that’s not the point.

It’s intriguing to imagine what Ellison could have written in the current political climate. But if Obama’s speeches (or his jokes) are any indication, then the president is his student—which explains both Obama’s clear-eyed sense of the absurdity that surrounds him, and his lack of discouragement when he speaks of the future.