Ghosts on Cloudless Days

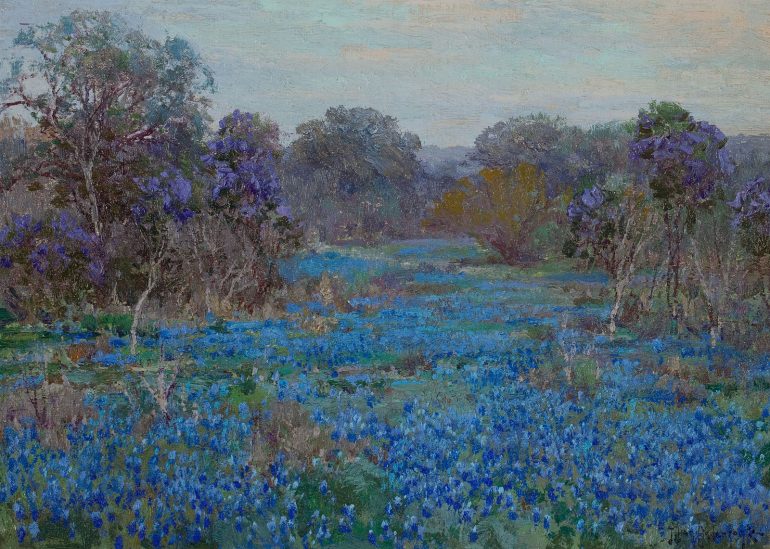

One of the things that I find strangest and most delightful about living in San Francisco is seasonal disorientation. Yes, it’s wetter or sunnier certain parts of the year, but there are no snowstorms or heat waves to convince memory to pin personal events to a seasonal timeline. I moved from the Northeast, where everything changes in the winter (right down to small talk: stay warm). The South, where I grew up, has winter, too: but, in the words of Katherine Anne Porter, it’s more like “a moribund coma, not the northern death sleep with the sure promise of resurrection.” She describes spring as “only a slight stirring, an opening of the eyes between one breath and the next . . . spring and summer at once under the hot shimmering blue sky.”

Southern spring, in Porter’s estimation, isn’t a full rebirth because winter isn’t a full death. Whereas spring further north leaps cleanly from receding snow and bare branches, southern spring is brief and muddled with the semi-cold winter that precedes it and the too-hot summer that follows. Springtime is a liminal space where the past seeps into the present. In literature, this mixing of climates, this stirring of the not-quite-dead, sets the stage for the introduction of the dreamlike and uncanny. Writing set in springtime also draws attention to cycles: familial, historical, and personal. It also can explore the breakdown of supposedly solid cycles and narratives.

Eudora Welty’s story “Asphodel” is set in a spring-like summer, in a meadow facing “a golden ruin.” In the story, three old maids gather for a picnic to retell the story of Miss Sabina, a woman who marries a wild man and loses all her children to various tragic deaths. Eventually, her husband, Mr. McInnis, runs off to Asphodel, his country estate, with a mistress. (In Greek mythology, asphodel flowers are associated with the afterlife.) Miss Sabina burns the estate in anger. She goes on to become a formidable figure in her little town.

Throughout the story, past and present coexist in dreamlike ways. To introduce the protagonists, who speak in chorus-like fashion, Welty writes: “They were not young. There were identical looks of fresh mourning on their faces.” The idea of “fresh mourning” is evocative: later in the story, we’ll find that they are mourning episodes from long ago. And the use of “fresh” to describe “mourning” gives an oddly youthful quality to the three women. Welty continues to use the language of both youthfulness and age to describe them: in one sentence she writes of “their narrow maiden feet” and in the next of their “gray and scanty hair.” The story they tell is similarly stretched between past and present, between relevance and obscurity: “its narrative was only a part of memory now, and its beginning and ending might seem mingled and freed in the blue air of the hill.”

A stark mix of past and present comes at the story’s end, when the women have a vision of Miss Sabina’s husband naked in the ruins of Asphodel. The moment is lush with spring and summer pastoral imagery: they run away “across the brook, and across the field in an aisle that opened among the mounds of wild roses.” They are unsure if they have really seen Miss Sabina’s husband, or if “it was a vine in the wind.” As they’re discussing, a herd of goats appears at Asphodel and begins chasing the women out. From their buggy, they throw biscuits, and then a chicken, until they escape the goats.

The story begins in a mythic mode—Miss Sabina’s tragic history, the ruins of Asphodel—but ends with a series of odd, comedic images. We see the women, previously full of grief, crying “‘Here, billy-goats!’” to the herd that’s started chasing them. And the story ends with the laughter of one of the sisters: “Her voice was soft, and she seemed to be still in a tender dream and an unconscious celebration—as though the picnic were the enduring and intoxicating present, still the phenomenon, the golden day.”

The word “intoxicating” recurs. Welty writes of the “old story” they’re telling: “In some intoxication of the time and the place, they recited.” The intoxication seems to come from the ruin, from the “cloudless day,” and from the resurrection of the past via retelling—which becomes literal with the vision of McInnis at the story’s end.

On a similarly “cloudless day” in San Francisco, I read “A Color of the Sky” by Tony Hoagland, a poet raised in the South. The poem reminded me of Welty’s “Asphodel,” though its setting is not explicitly southern. As in “Asphodel,” the sky in Hoagland’s poem is “baby blue.” It’s spring, or summer, or perhaps a mix of the two, and the present and past mingle:

Last summer’s song is making a comeback on the radio,

and on the highway overpass,

the only metaphysical vandal in America has written

MEMORY LOVES TIME

in big black spraypaint letters

It’s a sensual poem in which the speaker remembers old lovers as he drives through town. The landscape disorients: “What I thought was an end turned out to be a middle. / What I thought was a brick wall turned out to be a tunnel.” Musings on love and longing are paired with vivid images of the spring trees: “a little dogwood tree is losing its mind; / overflowing with / blossomfoam, / like a sudsy mug of beer; / like a bride ripping off her clothes.” As in “Asphodel,” Hoagland pairs images of springtime renewal with other cycles: recurring dreams, pop songs that cycle through the radio, petals that bloom and drop.

But though there are enduring cycles both in “Asphodel” and “A Color of the Sky,” underlying both works is the understanding that the narratives we use to give life meaning are ultimately as ephemeral as the seasons. In “Asphodel” the narrators are forced to reconsider the seemingly solid legend of Miss Sabina; “A Color of the Sky” ends with the image of Nature “making beauty, / and throwing it away, / and making more.” Seasons are paradoxical that way: just as they promise to order the year, to provide some sort of narrative for passing time, they disrupt our ideas of permanence.