On Accidental Books

Ann Patchett said of her 2013 essay collection, This Is the Story of a Happy Marriage, that a friend re-read the old essays she wrote during decades of supporting herself through writing journalism. She came back to Patchett with “a list of the essays she thought could make a book.” Patchett threw out a few from that list, wrote a few new ones, and said, “By this time those pieces were written it was obvious even to me that I was working on a book.” The result is a collection that traces the career of a young writer through the work she did to support herself while she wrote the novels for which she is best known.

There’s something intimate about knowing the genesis story of a book’s origin—how the spark of idea is ignited by a receptive and active mind—and reading it in its completed form. Patchett was paid by the word when her novels could not yet pay the bills, and her writing gained meaning as it grew and connected to new ideas and events in her life, eventually talking to each other in a meaningful enough way to become a coherent collection of essays. In some ways, it took her half a century to write this accidental book, her earliest silhouette as a writer darkening along its edges, informing the book she didn’t know she would write.

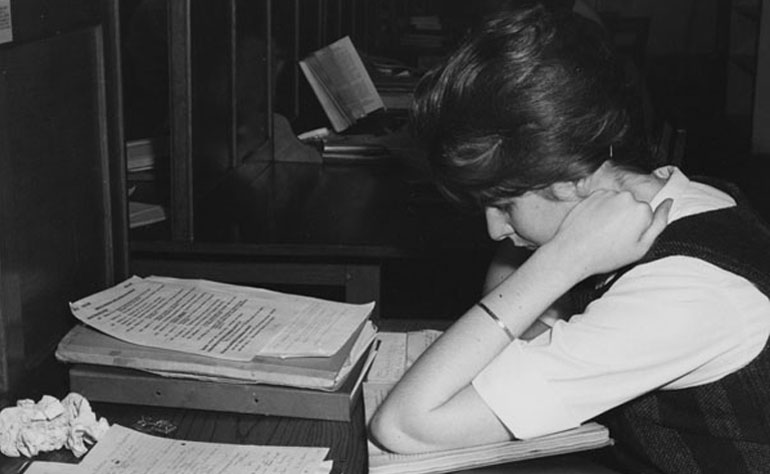

Accidental books like Patchett’s provide useful lessons in paying attention to the periods of rest between the projects we deem important and deliberate. After all, art does not come in wild fits, as it is often depicted in movies, and an artist does not simply drift aimlessly between breakthroughs. Inspiration does not strike if we are idle. Books, even books writers didn’t know they were writing, are born from discipline, by people who took their ideas seriously, even before they amounted to anything. The throughline of collections like Patchett’s, written by different selves over different decades, is collaged, held together by the writer’s voice.

Books don’t happen exactly by accident—Patchett still had to fill in what she had done since she stopped needing to write articles to make a living, notably get married, adopt a dog, and open up Parnassus Books. Plenty of writers have written accidental books, books accessing new entry points through which their creativity could best find its way to the page. Anaïs Nin wrote diaries throughout her life, eventually publishing them as volumes important in their work of centering a female voice among the pantheon of male celebrities she knew. Virginia Woolf wrote Moments of Being as disparate autobiographical sketches, which were found among her papers after she drowned herself, and eventually edited into a book in 1976. Alice Walker wrote in the preface to her 1988 collection Living by the Word, “This book was written during a period when I was not aware I was writing a book.” The list goes on and on of books that authors wrote over time, letting them gain power and connection without forcing them into the shape of a book until they said something complete—Sarah Manguso’s obsessive journaling turned into Ongoingness, Jenny Offill, who wrote Department of Speculation on index cards at traffic lights in LA. What, then, does “not writing” look like to people who end up writing important works of literature while they look away, toward some distant future in which they begin writing deliberately?

Anaïs Nin wrote, “I say to people that I am not writing, but I keep writing the diary, subterraneously, secretly, a writing which is not writing but breathing.” Without reflecting on the days she met a friend for a stroll, or did nothing worth noting in the grand scale of a life’s work, we readers would lose our intimacy with Nin, as she would surely craft a more curated version of quotidian life. Lucky for us, we have her diaries in all their rawness, in all their secrecy.

There is no such thing as writer’s block or procrastination if writers keep the faith and return, over and over, to the page. These books I mentioned, written without, at least at first, the author’s knowledge, remind me that the fallow periods of creativity are necessary to the lifecycle of a work of art, and often yield a harvest we couldn’t have predicted. If nature is cyclical, the seasonal bounty brief and abundant, then humans are probably no different. After all, inspiration needs something from which to draw—periods of living that can find their ways into the work we all do.

The lesson for us might be that it all amounts to something—the grocery lists and thank you notes, the kind of writing that clears the pipes or pays the bills. The same goes, of course, for all things; meaning floats to the surface, unhurried, through hard work and hard faith.