Only A Novelist Will Be Able To Make Sense of This Election

Years from now, the uncertainty and accompanying anxiety many of us have about the current political season may be displaced by different, more complicated emotions. Such perspective is cold comfort to the millions who are fearful of a possible Donald Trump presidency. For four years we have known that 2016 would usher in a new president, but even in this polarized season, the chasm of opinion between Trump supporters and everyone else seems to have come as something of shock. The number of times the political class has been wrong about Trump, and flagrantly so, only reinforces how far through the looking glass we are.

The coverage of the campaigns has not changed much from previous elections, the only difference being that, increasingly, it is now read on social media rather than in the newspaper. We are informed on policy positions and gaffes, what was said and wasn’t. In their efforts to explain Trump’s dominance, publications have found many explanations for his rise but few of them are satisfying.

As has been the case for other periods rife with turmoil, understanding Trump will be the domain of the novelists. Journalists covering the day-in, day-put grind of the campaign are hamstrung by the requirement of accuracy and the demand for timeliness. This is one aspect of modern communications the social media age has not disrupted.

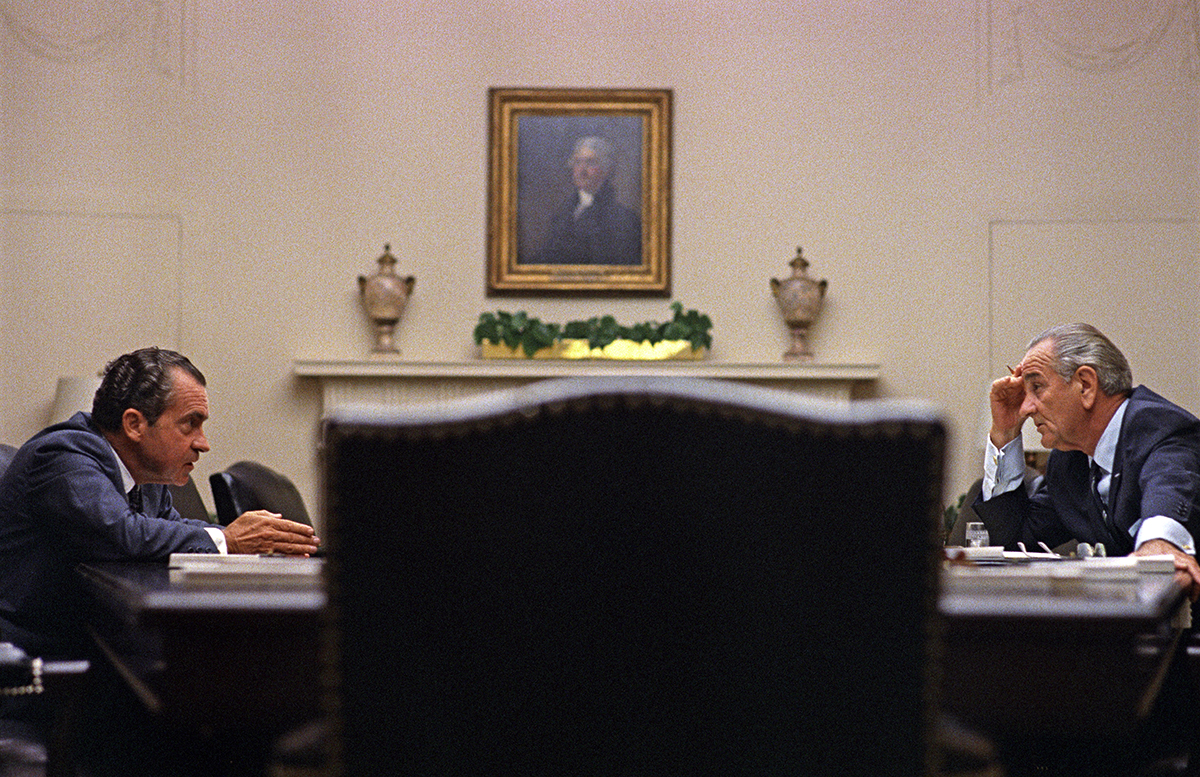

Elections do not exist in isolation. They are pushed and pulled by social, economic and cultural forces that are not always apparent in the moment. Novelists understand this. For example, it’s too easy to say that the election of the first black president led to a backlash by a substantial number of white voters who believe that after eight years of his leadership it is necessary for action to be taken to “Make America Great Again.”

The tradition of the author examining the present or recent past of the world he lives in is a long one. Don Quixote and Gulliver’s Travels are two of the earliest examples, both revealing the mores of the times in which they were written and critiquing those mores in the process.

But it’s been in the 20th and now the 21st century, as our capacity for communication has grown exponentially, that novelists’ ideas on issues of the day have gained greater currency.

To start with, has any novel captured time and place better than The Great Gatsby. Those inclined to learn about the Jazz Age would do well to begin their research with a copy of Fitzgerald’s best work.

One reason Gatsby and the Jazz Age is looked upon so fondly is because so much of the 20th Century was given over to bloodshed. With two world wars and other extended periods of carnage, Americans had little choice but to confront their feelings on warfare. Novels such as A Farewell to Arms, The Naked and the Dead, and The Things They Carried, which depicted World I, II and the Vietnam War, respectively, left little to the imagination.

Just as essential are those novels, like Gatsby, which chronicle the time between conflicts, in which we put the bloodshed behind us and extract meaning from it.

There are no better examples of this than George Orwell’s Animal Farm and 1984, both standing as eternal arguments against absolute rulers, published in 1945 and 1948, respectively. Around the same time, Robert Penn Warren’s All the King’s Men described just how intoxicating—and ruinous—the cult of personality can be.

For many, World War II was a “just war,” but Kurt Vonnegut’s Slaughterhouse Five and its whimsical depiction of massive loss of life—often at the hands of Allied troops—erased much of the nostalgia Americans had for the war.

America after World War II and during there Cold War, was a society of affluence, but the keen eyes of novelists like Don DeLillo, Thomas Pynchon and Tom Wolfe raised provocative questions about how that affluence was achieved. Each author, in one novel after the other, described an America with a guilty subconscious (DeLillo’s White Noise and Underworld), fraying at the seams (Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow) and trying to sew itself back together

through mythology and greed (Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities).

More recently, David Foster Wallace’s Infinite Jest put an over-caffeinated hyper-connected America under the literary microscope. Like Wolfe, some of Wallace’s best prose came while writing non-fiction.

Wallace’s heir may very well be Ben Fountain, whose Billy Lynn’s Halftime Walk, published in 2012, documents an America still reeling from terrorist attacks.

So, which author will make sense of Trump for us? Given the subjects of Trump’s demagoguery and the fact that every author mentioned in this blog has been a white male, it’s a fine time for a woman or person of color to have the honor. I suspect Megan Kelly would happily help promote the book once it’s released.