Other Countries

Sometimes I have to remind myself that the Black Writer In America is a cosmopolitan entity. The news can do that to you, even in February. Obviously there’s Harlem, and before that, there was the mass exodus from the South to the North, to experience life among people who wouldn’t hit you for wanting it. But what might be less obvious (or maybe it’s just me) was that there was a time when it wasn’t unheard of to abandon the U.S. altogether. You’d leave your respective pocket of Oklahoma, or Mississippi, or New York for a life in Europe—a decidedly less hostile locale. You’d do it with the hope of transcendence. In pursuit of the benefit of the doubt.

Writing about his experience abroad, Richard Wright called it “interesting”:

There was a liberty ship fill of G.I.’s pulling out for home, and they chanted and shouted to us incoming Americans: “you won’t be sorry”… I never felt a moment of sorrow for having lived in France. I find Paris a city whose sheer physical beauty feeds and nourishes the sensibilities of all those who live in it.

It’s worth noting that the “all” wasn’t a casual throwaway. Wright came up in Chicago, in 1927, after enduring adolescence in the Jim Crow South, and by the time he’d made it to Europe it was the late 1940’s. It’d be another 15 years before the Montgomery bus boycotts, and nearly 23 before MLK’s “Letter From an Alabama Jail.” “All” wasn’t the standard in his country.

But in Paris, Wright became familiar with Jean-Paul Sartre and Camus. He lived in the company of Chester Himes and Baldwin, in the vicinity of Josephine Baker, Arthur Briggs, Sidney Bechet, and Kenny Clarke. All of them black artists, all of them trafficking culture, all of which would’ve been inconceivable had they stayed in the fifty states. Theirs were two parallel existences, with no conceivable precedent, and while it would’ve been nice for them to finally meet, none of them were banking on it at the time.

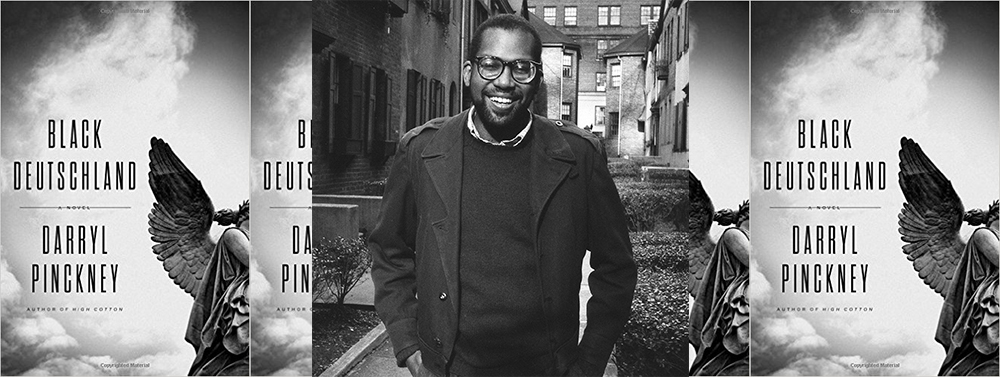

For the most part, those tracks still haven’t collided, but in Black Deutschland, Darryl Pinckney’s new novel, we’re given the closest thing in years: the chronicle of a gay black American in Berlin. The time is the present. West Berlin’s been commercialized. Pinckney’s narrator does a number of things in Germany—Jed looks for white boys, he attempts to float his writing career, he tries not to relapse into his bout with alcoholism—but while the novel’s context is obviously in light of race relations back home, the novel itself isn’t explicitly about race. The trials Jed faced in Chicago are very much a part of him, but he isn’t “escaping” them. He’s no Chico. Moreso than The Black Homosexual Escaping America for Europe, Jed is a dude who has moved in search of beauty:

“After those few summers of desperate rehearsal, tourist make-believe, I was recently sober and alone in a train compartment about to be locked tight for the border crossing between the fast-driving, exhibitionist German Federal Republic and the paranoid German Democratic Republic, with its harsh fuels. I’d left Chicago for good. I was inordinately proud of my one-way ticket. I’d become that person I so admired, the Black American expatriate.”

I won’t front like I knew about Pinckney before this novel (now I know), but it’s a novel we’ve needed, and it makes sense that he’s who’s written it—it touches on themes his criticism has circled for years.

Pinckney’s touched on Pushkin’s novella “The Negro of Peter the Great”, the conflicting vantages of Ava DuVernay’s Selma, altered states of consciousness in Romantic Literature, and the rush of shaking Jimmy Baldwin’s hand after panning his final novel “from the typewriter of Mr. Little Shit.” He has noted, on multiple occasions, that

And again, as it were. And again, and again, and again.

So begs an important question—when the author can’t make a home out of her country, just how far does she have to go to find one? And if it takes the American artist transplanting themselves to Beirut, or Mexico City, or Lisbon to come to terms, can they ever really adopt it? Can they really, really claim it? Because, as Major Jackson has noted elsewhere, the American author has greater access to the world than ever before, “but ironically we lack not only awareness but global relevance.”

I’ve always believed the artist makes a home in their residence. The works I love are place-centric, the sort of thing I’d like to write someday. But Pinckney raises a dilemma in transplanting his protagonist from Chicago to Somewhere Else—whether Home is simply wherever you find yourself at the time, or the accumulation of what you’ve brought with you, what all you’ve left behind.

It took Pinckney upwards of twenty years to write this book—which isn’t a criticism, the mastery is evident—but I couldn’t help wondering whether the catalyst for a look at life abroad, in lieu of Isherwood, was a reaction to the situation at home. I wonder whether this apparent hostility will be the catalyst for more works, from other black authors, from the outside looking in. Work after work in pursuit of a better somewhere—only somewhere else. I wonder whether Pinckney, in his hiatus, thought to pursue the fluctuations in the public’s perceptions of African Americans over the past thirty years, and what that novel would look like. I wonder if one day he will sit down and write about it. I do hope, if not him, then somebody will. But then again, it isn’t the artist’s responsibility to reign in tome after tome of the times; as Susan Sontag’s told us, “the point of a writer’s life is to produce a great book—that is, a great book will last.”

It’ll be up to everyone else to confer the longstanding merits of Black Deutschland, but I think it is a great work. I will remember it.