Our Lady of Intercession

You are the door, not the one who walks through it.

This is the axiom, the rule, that Makina, the tough-as-she-is-smart-as-she-is-sexy protagonist turned undocumented pilgrim issues to herself early in Yuri Herrera’s Signs Preceding the End of the World, published in the U.S. in 2015. The third book in a trilogy and the first of Herrera’s novels translated and issued in English, Signs has sparked considerable critical acclaim.

Much of that commendation is steeped in laudatory comparison to other hallowed writer-bros of the Spanish-trans-English persuasion: the Argentine Jorge Luis Borges, the long-exiled to Mexico Chilean Roberto Bolaño, and most frequently Mexican-born Herrera’s own countryman, Juan Rulfo. Comala—the literal ghost town of Rulfo’s sole novel Pedro Páramo (1955)—became the instigating terrain for the Latin American Boom’s chief hallmark: magical realism. “This town is filled with echoes,” Rulfo writes of the haunted place his protagonist arrives in search of a father, a patria, he’s never known. Many literary critics have plotted Comala as the precursor to the Macondo of Gabriel García Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude (1967), the most celebrated book of the Boom’s cannon. García Márquez is said to have known the whole of Pedro Páramo by heart. Comala’s reverberations, its specters, its whispers (“the murmuring killed me” says one of the town’s victims) served as fertile ground for other otherworldly imagination.

Herrera has demurred from these comparisons, especially to Rulfo, saying in an interview, “He’s not one of my intimate, personal authors.” But Herrera’s heroine Makina is haunted by her literary antecedents. Just as Rulfo’s Susana San Juan—the protagonist’s aquamarine-eyed, ghost-visioning object of affection—occupies a coeval position between the living and the dead, so too, is Makina made to be the intermediary between one world and another. The woman, like the door, both hinged and unhinged in the text—an intercessor on whom all possibility rests.

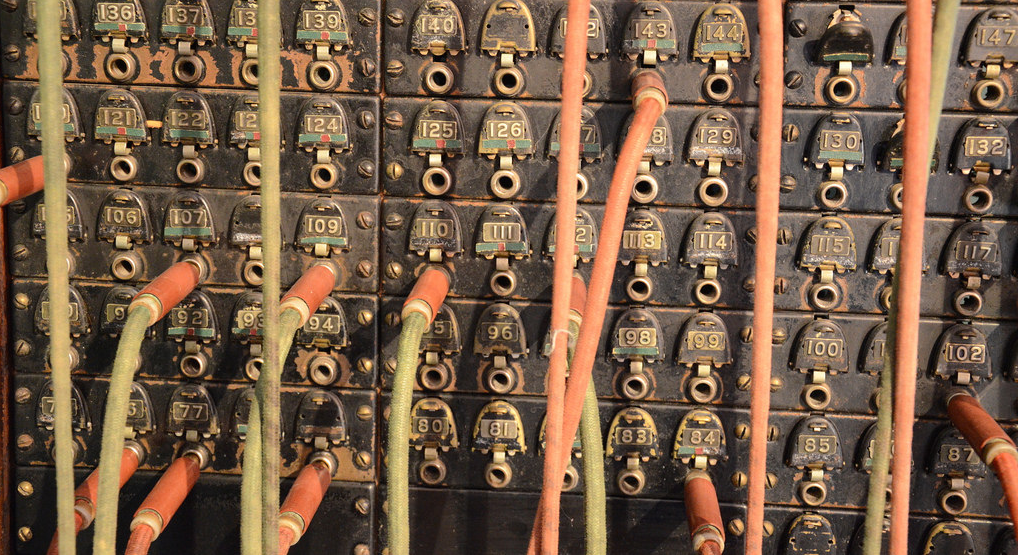

For Makina her go-between is quite literal. She runs the switchboard in a small, rural village—“the only phone for miles and miles around.” She fields calls and makes connections from near and far. Her body is a node for the “the passions that came and went along the phone cord,” and a transistor for the uneven distributions of neocolonial technology. I mean: operating a switchboard seems even more distant than owning a boombox in these United States. Yet, when Makina crosses the border from Mexico to the U.S. in search of a long-lost brother it is this part wire-part flesh connection that she longs for. “And what about the switchboard,” she wonders, “how would it look and feel without her?”

Makina’s vocation calls to mind the unnamed lady telegraphist of Henry James’s In The Cage (1898), a character who possesses what the feminist literary critic Maude Ellman has called an “obsession with covert transferences between others.” From the captivity of her latticework cage in a London grocer—the “framed and wired confinement” of class, gender, and actual barrier—she is a receptor for “the words of the telegrams thrust, from morning to night” through her rough and tumble fencing. This coarse permeability of the eponymous cage set in the self-exile of James’s London is not so distant, woven as it is into the warp and weft of Transatlantic commerce and culture, from the dismantled baracoons of a natal America deep in the Jim Crow era. “The barrier was,” James writes, “a frail structure of wood and wire; but the social, the professional separation was a gulf.” When the telegraphist involves herself in the illicit love affair of two upper class blow hards, the boundaries come crashing down. And yet, at the novel’s close, our telegraphist opts to stay in her lane, marrying her intended fiancé, the evocatively named, Mr. Mudge. Snooze alert. At the cusp of modernity and with the New Woman ideal looming large, James’s text ends in a swerve. Border crossing is a dalliance, not a way of life.

In Herrera’s text, border crossing is not only a way of life, but life’s very method of survival. And, so, it may be indigenous figures—“homegrown” in Herrera’s parlance—from who Makina draws her archetypal inheritance. She’s not only the broker of communications, she’s also communication’s interpreter. “Sometimes they called from nearby villages and she answered them in native tongue or latin tongue,” Herrera writes, meaning an autochthonous and Spanish language. “Sometimes, more and more these days, they called from the North; these were the ones who’d often already forgotten the local lingo, so she responded to them in their own new tongue,” he continues, intending English. “Makina spoke all three, and knew how to keep quiet in all three, too.” Whereas James’s telegraphist intervenes in cryptic communication, Makina is its sole and stolid purveyor.

Much has been made of Sign’s relationship to the myth of Mictlán, but the cosmologies of post-Columbian conquest negotiated are operative too. Makina’s interpretative powers echo the transit from the Mesoamerican feminine deity Coatlalopeuh to the Marian figure of the patrona Our Lady of Guadalupe. Guadalupe appeared first, or so the story goes, to Juan Diego, a poor Indian boy, in 1531, speaking in the Nahautal language of the Aztec empire. She was almost immediately transliterated and venerated by the Catholic Church of the Spanish colonial empire—a symbol of synthesis according to the Chicana theorist Gloria Anzaldúa. “Guadalupe unites people of different races, religions, languages: Chicano protestants, American Indians and whites,” Anzaldúa schematizes. “‘Nuestra abogada siempre serás / Our mediatrix you will always be.’ She mediates between the Spanish and the Indian cultures (or three cultures as in the case of mexicanos of African or other ancestry), and between Chicanos and the white world. She mediates between humans and the divine, between this reality and the reality of spirit entities. La Virgen de Guadalupe is the symbol of ethnic identity and of the tolerance for ambiguity that Chicanos-mexicanos, people of mixed race, people who have Indian blood, people who cross cultures, by necessity possess.” But Makina isn’t just the symbol of mestizaje under global currents. She, like Guadalupe, is the conduit to cultural crossing.

When she hears an “intermediary tongue” in her travels, Makina is taken with it. Herrera writes, “It’s like her: malleable, erasable, permeable; a hinge pivoting between two like but distant souls, and then two more, and then two more, never exactly the same ones; something that serves as a link.” Even in the allegorical epic frame, Makina’s body as the threshold space—the zaguán, the umbral, that door swinging on its rooted hinge—undercuts all the brassy strength with which Herrera has imbued her. Instead, she’s meant to guard a proverbial home at the same moment she is tasked with necessary departure from this home’s hearth. It rings like the imploring John Donne in his “Valediction Forbidding Mourning,” “As stiff twin compasses are two; / Thy soul, the fixed foot, makes no show / To move, but doth, if the other do.” It’s this formulation that I find troubling: at once home and away, Makina’s power lies in her cultural and biological permeability.

It’s one thing to effect permeable borders, quite another to insist on violable bodies to constitute the border’s apertures.

“I keep my grief hidden in a safe place,” says Rulfo’s Susana San Juan of her sadness, her occluded vulnerability. In Herrera’s text the oracle-like Señor Q tells Makina, “and even though you’re sad you’ll get where you need to go.” Which is to say: she’ll walk through that prohibited door.