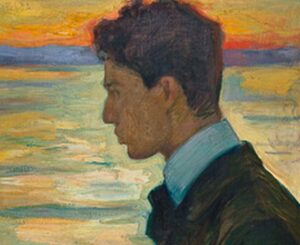

Pasternak: the People’s Poet

It’s been 100 years since the Russian Revolution of 1917 toppled Tsarist rule, leading to the socialist system that would come to be known as the Soviet Union. Boris Pasternak is best known for writing Doctor Zhivago, a novel which documents these years of national upheaval through the eyes of a poet and physician. Like his eponymous character, Pasternak was famous in his native Russia for his verses.

The end of the novel sees the fictional Zhivago’s poems laid out for readers. Thematically, they cover love, death, and religion. The most moving are the ones that relate to Zhivago specifically, often written in first person. These poems communicate the disorienting effects of the revolution and its aftermath on the daily lives of Russian citizens through the experience of Zhivago and his beloved Lara.

On paper, these poems are neat, brief, four-line stanzas with simple titles like “White Night,” “Autumn,” “A Winter Night,” “Separation,” and “Dawn.” Many of them serve a practical purpose—to chart narrative events in the novel such as Lara’s leaving Zhivago and the town of Varykino and the doctor’s subsequent hours spent alone there, writing and longing for her return.

One such poem is the rhapsodic “White Night” in which Zhivago imagines himself and Lara as two lovers sitting on the windowsill looking out at the newly arrived daylight. They can still hear the nightingale’s song:

The crazy trilling surges, rolls,

The voice of the little homely bird

Awakens ecstasy and turmoil

In the depths of the enchanted wood.

The bittersweet tone of regret and specific references to the nightingale bring to mind a brief scene from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, in which the titular pair lovingly banter over the time of day based on what birdsong is heard outside. Pasternak, a prolific literary translator throughout his life, tackled this famous play while penning portions of Dr. Zhivago, and so may have very well had this scene on his mind.

Pasternak’s seemingly innocent depiction of night as something white and light-filled proves unsettling as this poem progresses. The final stanza confirms the unavoidable despair that strikes the lovers when daylight breaks:

And the trees, like white apparitions,

Pour in a crowd out to the road,

Waving as if to bid farewell

To the white night that has seen so much.

So many living in Russia during this chaotic time had, like the night, “seen so much.”

The more erotic “A Winter Night” could easily be the dark, interior-focused counterpoint to the nature-centric world of the previous poem. The refrain “A candle burned on the table, / A candle burned” is repeated four times throughout the poem.

The religious vein of Zhivago’s later poems surfaces in “A Winter Night” with the lines:

Shadows lay on the ceiling

In the candlelight

Crossings of arms, crossings of legs,

Crossings of destiny.

[…]

And the heat of seduction

Raised up two wings like an angel,

Cruciform.

A sense of urgency pervades this repetitive poem, a sense that Lara and Zhivago haven’t much time, that their existence hangs in the balance, and that they’ll be pulled apart by the hands of fate soon enough.

A word and theme used throughout the poems is that of destiny. The mournful poem titled “Dawn” begins with the line “You meant everything in my destiny.” In the novel itself, Zhivago and Lara are destined to be together: “They loved each other because everything around them wanted it so: the earth beneath them, the sky over their heads, the clouds and trees.” There’s no fighting the laws of nature, as it’s frivolous resisting a revolution hundreds of years in the making.

The end of “Dawn” recalls the current state of life in Russia:

With me are people without names,

Trees, children, stay-at-homes.

Over me they are all the victors,

And in that alone lies my victory.

Here, Pasternak layers anguish with uplift, making life seem livable, though history and those who read the novel when it was first published knew it to be otherwise for so many involved. In this poem, Zhivago finds solace in the masses and the progress of the people as a whole, rather than as individuals.

Perhaps politics can’t be fully stripped from these poems, but Pasternak was a writer of his time, trying his best to make sense of a world turning upside down all around him. The undercurrent flowing beneath the lines is a search for meaning and personal connection. Pasternak’s awareness of the wide world coupled with a sensitivity toward the smaller, more intimate one, are what make his poems and fiction endure.