People of the Book: Mara Mills

People of the Book is an interview series gathering those engaged with books, broadly defined. As participants answer the same set of questions, their varied responses chart an informal ethnography of the book, highlighting its rich history as a mutable medium and anticipating its potential future. This week brings the conversation to Mara Mills, a professor of media, culture, and communication at New York University who engages with disability studies and new reading formats.

1. How do you define a “book”?

I wrote to some of my colleagues at the Library of Congress to see if they had an answer to this question, and none of them did! It’s much easier to characterize a book or reading format. Blind and other print disabled readers have long understood books to come in different forms: inkprint, embossed print, braille, and Talking Books. (A current list of accessible reading formats can be found on the website of the San Francisco LightHouse for the Blind and Visually Impaired.) Digital reading technologies have prompted a widespread acknowledgment of the heterogeneity of books.

Artists like Tan Lin are particularly expansive with regard to “the formats and micro-formats of reading.” His Seven Controlled Vocabularies and Obituary 2004. The Joy of Cooking is a book about paratext and meta-data; books as commodities; translation and machine reading; “ambient textuality” and “non-print forms of reading.” Among many other things, 7CV contains English and Chinese text, machine code, found photographs, scanned clothing tags, and samples from other books. It exists as a print book, an RSS feed, and a pdf available through Lulu.com; there’s also a Flash video of the first chapter. The appendix can be found on TUMBLR.

11 ancillary books have also been released by Edit Publications (University of Pennsylvania), including a critical reader, a compilation of technical documentation, and three Chinese editions. I haven’t finished reading 7CV; there may be other formats. “There is really no such thing as a book from the perspective of a reading system,” Lin says.

2. How do you engage regularly with books, beyond reading?

My girlfriend is an English professor and an insomniac. She spends hours reading in bed each night, inkprint and iPad. She reads things aloud to me: brilliant passages in unpublished manuscripts, riddles I fall asleep too quickly to solve, Facebook posts. (I don’t have a Facebook account; it’s an oral medium for me.) She’ll describe the plot of one of the crime novels she’s been reading lately. She has an incredible talent for summary. Around four she wakes up and starts reading again. If the lamp bothers me, or the screen, I’ll ask “What’s happening,” pulling a blanket over my head as she tries to catch me up. I have dreams about Malmö, friends of hers I’ve never met. After ten years, so many books are familiar to me, but I can’t be sure I’ve read them.

In my research on the history of Talking Books, I’m experimenting with a decoding strategy I think of as co-reading. Talking Books have circulated via the Library of Congress NLS system since their initial production in the 1930s, and they are published with legal exemption from copyright fees. Whether in LP, tape, or digital form, Talking Books can only be obtained by subscribers with a medical certification of “print disability.” (They could be called prescription media.)

Early Talking Books records were labeled, in print and in recorded prefaces, “solely for the use of the blind.” Here’s an example from the opening of Oscar Wilde’s The Happy Prince, read for the Library of Congress program in 1943 by lesbian Broadway star Eva La Gallienne. The requirement of NLS certification continues to this day. As a sighted researcher, I rely on friends and colleagues who are NLS subscribers to read copyrighted Talking Books and excerpt short passages for me—or else to describe interesting narration and navigation strategies. This co-reading is motivated less by respect for copyright law than the minoritarian history of the format.

3. What has been your most unusual interaction with books?

Growing up in Portland, Oregon, I spent many rainy days reading and playing in the basement. My parents kept an open Bible on a bookstand in the living room (replaced by a dictionary at some point when I was in middle school). This Bible became an element in my childhood rituals—the kind that aren’t passed down in books.

My best friend lived kitty-corner from me. Some weekend afternoons, we would skim the Bible for a fearsome page, tear it out, and smuggle it down to the basement. We’d prick our thumbs with a school compass, press them together to become “blood sisters,” read the page aloud, then toss it into the furnace, watching it leap into flames. This was sometimes capped with a round of fainting, achieved by breathing heavily while doubled over, then quickly standing.

I knew the Bible was a household object with many functions. Foremost, record-keeping: photographs, pressed flowers, and funeral programs were stored between the pages; family history was written in the endpapers. And history could be altered by the ones in charge of the book. For giving syphilis to his wife, my maternal great-grandfather’s name was inked out of the family tree at the front of a Lutheran Bible that dated to the 1700s. This occurred in the 1920s in the town of Haparanda in Northern Sweden, not long after he had returned from a three-month ski trip across Finland and into Russia.

Shunned, he moved his young family to Detroit, first sailing to Ellis Island on the Olympia, sister ship to the Titanic. He became a bookkeeper, evidently cured by sulpha drugs. His wife went mad from neurosyphilis, dying in 1943 after several years of residence at Ypsilanti State Hospital. Their children left home as teenagers; my grandmother married and eventually moved west.

On her husband’s side, a Catholic Bible had been brought over from County Cork during one of the Irish Famines. It was known to contain family secrets. At some point, my great-aunt Agnes, “a spinster who lived all her years with her mother,” set fire to the Bible in Davenport, Iowa. My grandfather’s family moved once again, to Detroit, free from history.

4. Do you have favorite tidbits from the history of books?

In the 1930s, as staff at the American Foundation for the Blind began recording Talking Books at their studio in Manhattan, they quickly stretched the concepts of books and reading far beyond the formulation of “aural literature.” Some of the first Talking Book playback machines were multipurpose radio-phonograph devices, and early adopters put them to nonliterary uses: listening to musical records and radio shows. An internal memo from 1935, held in the Talking Book Archives, makes clear the extent to which the AFB was willing to redefine the book:

We felt that the system…should also be capable of reproducing any of the commercial recordings in the market…any musical composition recorded is a book just as much as any novel so recorded, and it would be eminently unfair to deprive the blind of the facility to listen to these commercial “musical books,” as well as to our “reading books.”

The AFB likewise produced a highly popular set of birdsong recordings with Professor Arthur Allen of Cornell (American Bird Biographies), prompting discussion about a new genre of “sound-picture-books.” In 1938, the AFB sponsored a recording of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarves. Widely advertised as the first conversion of a Talking Picture into a Talking Book, it combined dialogue and music from the film soundtrack with narration by George Kean, who described the animated scenes and even attempted to create verbal analogies for each character’s musical theme.

5. What material part of the book interests you most?

In terms of print books, typeface. For one thing, I’ve recently been working on the history of optical character recognition (OCR); in particular, experiments in the 1950s-1970s with standardized fonts that machines could read.

I’ve also been investigating the history of typeface on eye charts for measuring visual acuity. As one example, Eduard Jäger of Vienna published a series of “Schrift-Scalen” or “Test-Types” in 1854 to assist with the prescription of lenses. He created scaled excerpts of literature, printed in typeface familiar for a given national context. In German, he took passages from Goethe, Herder, and Schiller, printed in Fraktur. For English, a sentence from the Dickens’ story “The First of May,” in Bodoni. Modified versions of Jäger’s Schrift-Scalen are still used to test near vision today.

Distance vision came to be tested with eye charts made up of individual characters, such as Snellen’s famous “optotypes.” Ophthalmologists tinkered with typeface, letter choice, size, and spacing for a century after the introduction of Snellen’s first chart in 1862. Additionally, a “newsprint reading test” began to be employed by the U.S. national census in 1900 to sort blind from sighted people. Through these kinds of examinations, reading became naturalized, if not a required bodily function. Moreover a new category of “legally blind” people emerged, 90% of whom had some sight.

As for Talking Books and other sound formats, a specific feature I’m currently researching is the audio description of images. How is a chart, a photograph, an illustration converted into spoken language? What are the protocols for a graphic novel? Which aspects of an image are most salient for verbalization? What seem to be the visual cues of sexuality, race, affect, nationality, and how are these put into words?

6. If your house was burning and you had to take three books, which would you save? Why?

I have so many irreplaceable print books that I wouldn’t want to see burn: scrapbooks, rare books from my work as a historian, gifts made by artist friends. Here are three: I carried around a paperback copy of Kafka’s Amerika for a few crucial weeks one summer when I was in high school; my teenage revelations are recorded in the margins and flyleaves. (Sex acts, visiting cities, drinking red wine.) At some point, my daughter removed the book from one of my shelves; I’d have to steal it out of her room to save it.

Bookmaking was a pastime for my children when they were young. Dozens of their books were lost, among other papers and photographs, in a basement flood. One that remains is The Great Book of Hairdoes. Sheets of “business paper” stapled together, an hour’s work. (See excerpt at right.)

My girlfriend gave a series of books to me during our first few months of dating, each inscribed tenderly and at length. I was doing coursework for a Master’s in Biology at the time and didn’t understand some of these books, or why they were being given to me. (A Lover’s Discourse by Roland Barthes, yes, but Spurs by Jacques Derrida?) The first in the series—the one I would save—is a copy of Laura Letinsky’s Venus Inferred, a photograph book of intimate couples. Lauren Berlant wrote the introduction. She says of Letinsky’s domestic scenes: Sexuality is presumed to guarantee something meaningful about personhood or a person, which means that something else is hailing you: not sex, but the conventions of the intimate. This world is more like the “Beyond” of “Bed, Bath, and Beyond.” A fragment from the inscription to me reads, “Please forgive the comfort.”

7. What about the current moment for books interests you?

I’m interested in the way new reading formats require new forms of reading. I’m especially interested in the details of reading practices: gestures, sequences, habits of attention. I also want to understand how books are connected to knowledge, feelings, and the formation of communities. Can one read with any of the senses? What does decoding feel like across different formats? Why are certain symbolic forms idealized? What does it mean to affiliate around a technology or decoding practice (e.g. to be part of “the audiobook community”)?

8. Where do you go to find and/or give away books?

For gifts, the Rare Book Room at the Strand or Joanne Hendricks Cookbooks. For my own reading, I spend a lot of time in the research libraries at deaf schools and blind schools, where I find books to borrow or to purchase elsewhere (usually through websites like Biblio or AbeBooks): short run memoirs, out-of-print medical texts and technical manuals, schoolbooks in various formats.

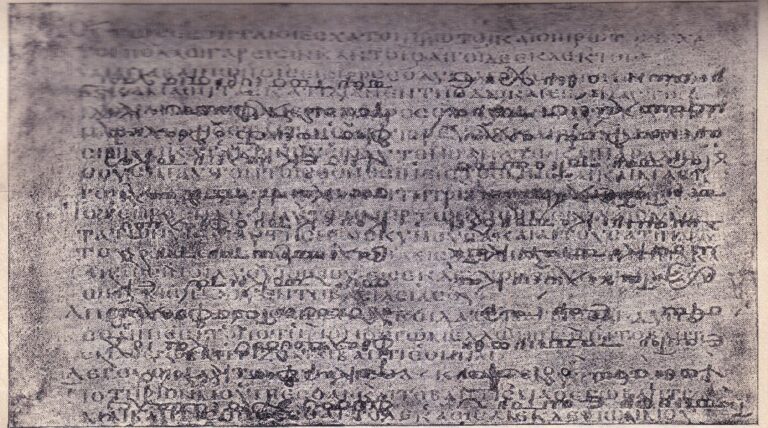

Many U.S. states established public residential schools for deaf and blind students in the nineteenth century. Although some have closed as students are mainstreamed, at other schools, librarians and alumni have maintained significant archives and museums. In Massachusetts, the Perkins School for the Blind has an exquisite research library. Founded in 1880 and continuously expanding, its holdings range from Laura Bridgman’s manuscripts to Kurzweil product pamphlets. I try to read historical books in the context of their original use, alongside contemporary or related books and journals; the annual reports of librarians; letters and reviews and schoolwork. I wish I could say I gave away books, but I live in a household of hoarders. Above is a photo of an entryway in my apartment.

9. How do you foresee books evolving in the future?

Screen reading has to change. Psychological and sociological studies continue to enumerate the drawbacks of reading on present-day screens: distraction, eye strain, awkward navigation. In a recent Scientific American article (“Why the Brain Prefers Paper”), Ferris Jabr went so far as to say that “screens impair comprehension.” And for blind readers, many e-books and websites remain inaccessible. We’re at the very beginning of an era of electronic reading. Technical changes will be rapid and often short-lived. Likewise, it will be a long time before any consensus emerges about the social meaning of reading across these new formats.

Mara Mills is an Assistant Professor of Media, Culture, and Communication at New York University who works at the intersection of disability studies and media studies. In her current research project, Print Disability and New Reading Formats, she investigates the transformation of print over the course of the past century by blind and other print disabled readers, with a focus on Talking Books and electronic reading machines. With Matthew Rubery, she has co-organized a June 2014 conference at the Wellcome Collection on Blindness, Technology, and Multimodal Reading.