Phonesthesia: Poetic Sound and Diegetic Noise

Can poetry, through its command of sound, represent physical spaces, objects, and movement? Can one describe something—a setting, a object, a person—and also synesthetically render it for the reader? These are questions that have obsessed me for years, ones I ask every time I sit down to draft and revise. Can I orchestrate a whole landscape to my reader in the same way that Aaron Copland gave us the sound, albeit dramatized, of America in Fanfare for the Common Man? Can I make a horse neigh in a poem without telling the reader that a horse neighed in a poem?

*

When I was in high school, I was one of two first trumpets in the symphonic band, and every year we had a Christmas concert in which we played Leroy Anderson’s “Sleigh Ride,” which was underscored by a perpetual bell shake and wrapped up with the trademark sounds of a horse: a clip-clop-clip-clop-clip-clop from the woodblock and a whinny from the trumpet. The trumpet player creates the whinny sound by rapidly releasing and stopping air in the mouth piece while gradually loosening one’s lips while also fanning a cup mute over the horn’s bell. I liked playing the part when I could, because it seemed to be beyond music, beyond notation. It made the sleigh ride seem—almost—real.

*

I’m suspicious of onomatopoeic language in poems, especially when it drifts toward language poetry. (See Michael McClure’s Ghost Tantras written in “beast language,” which Maggie Millner described in her review of the City Lights re-release as having the “effect of defamiliarizing even the most recognizable and correctly spelled words—so ‘leaf’ is as much a truncated shriek as a word for part of a plant.”) I’m not a good comic book reader either, as I’ve often found the onomatopoeic insertions of crack, zip, and bampft seem like a bad FX reel. By no means am I calling for ciss-boom-bah (buh-dum chhhh) in our poems, just a little diegetic sound.

*

In grad school, I had to assist a 150-student humanities course called Readings in Film. All I remember from the class is that the eighteen-year-olds’ consensus was that “Sissy Spacek is a bad actress” and that the difference between diegetic sound and non-diegetic sound is that the first refers to sound whose source is visible on screen (e.g. character’s speech, a door shutting) and the latter refers to sound that’s overlaid onto the film, like narration or a soundtrack. For me, the distinction is important in poetry; only, I want to make the non-diegetic sound, the orchestration of poetic language, seem more like the diegetic sound found within settings of the poems.

*

Several years ago when I was a student in a conference workshop, a faculty member brought in Wordsworth’s Prelude to our class and had us read the first book’s ice skating scene, which I won’t deny you the pleasure of reading for yourself:

All shod with steel,

We hissed along the polished ice in games

Confederate, imitative of the chase

And woodland pleasures,—the resounding horn,

The pack loud chiming, and the hunted hare.

So through the darkness and the cold we flew,

And not a voice was idle; with the din

Smitten, the precipices rang aloud;

The leafless trees and every icy crag

Tinkled like iron; while far distant hills

Into the tumult sent an alien sound

Of melancholy not unnoticed, while the stars

Eastward were sparkling clear, and in the west

The orange sky of evening died away.

Not seldom from the uproar I retired

Into a silent bay, or sportively

Glanced sideway, leaving the tumultuous throng,

To cut across the reflex of a star

That fled, and, flying still before me, gleamed

Upon the glassy plain; and oftentimes,

When we had given our bodies to the wind,

And all the shadowy banks on either side

Came sweeping through the darkness, spinning still

The rapid line of motion, then at once

Have I, reclining back upon my heels,

Stopped short; yet still the solitary cliffs

Wheeled by me–even as if the earth had rolled

With visible motion her diurnal round!

Behind me did they stretch in solemn train,

Feebler and feebler, and I stood and watched

Till all was tranquil as a dreamless sleep.

Wordsworth tells the reader of the act of ice skating in the first and second lines of the excerpt—“All shod with steel, / We hissed along the polished ice”—but he doesn’t stop there with his rendering of the space and the action. The poet supports the description with sounds that mimic the ambient noises the action, mostly with es-sy (not a technical term) sounds sometimes compounded with other, breathier consonants: shod with steel / hissed / polished ice. Because the poet sets up an equation between the action of ice skating and the sound of the skates on ice here, the rest of the passage’s sounds read with the same sort of ambient soundtrack. Can you hear, like me, the skates among the leafless trees and the solitary cliffs, sweeping through the darkness? The other language here does some work, and I could spend hours picking apart the way an l might seem like the skater’s changing direction or how the prosody speeds and slows us in time with the skater’s motion, but I won’t indulge all of these conspiracies here.*

Bouba-Kiki Effect and Phonesthesia

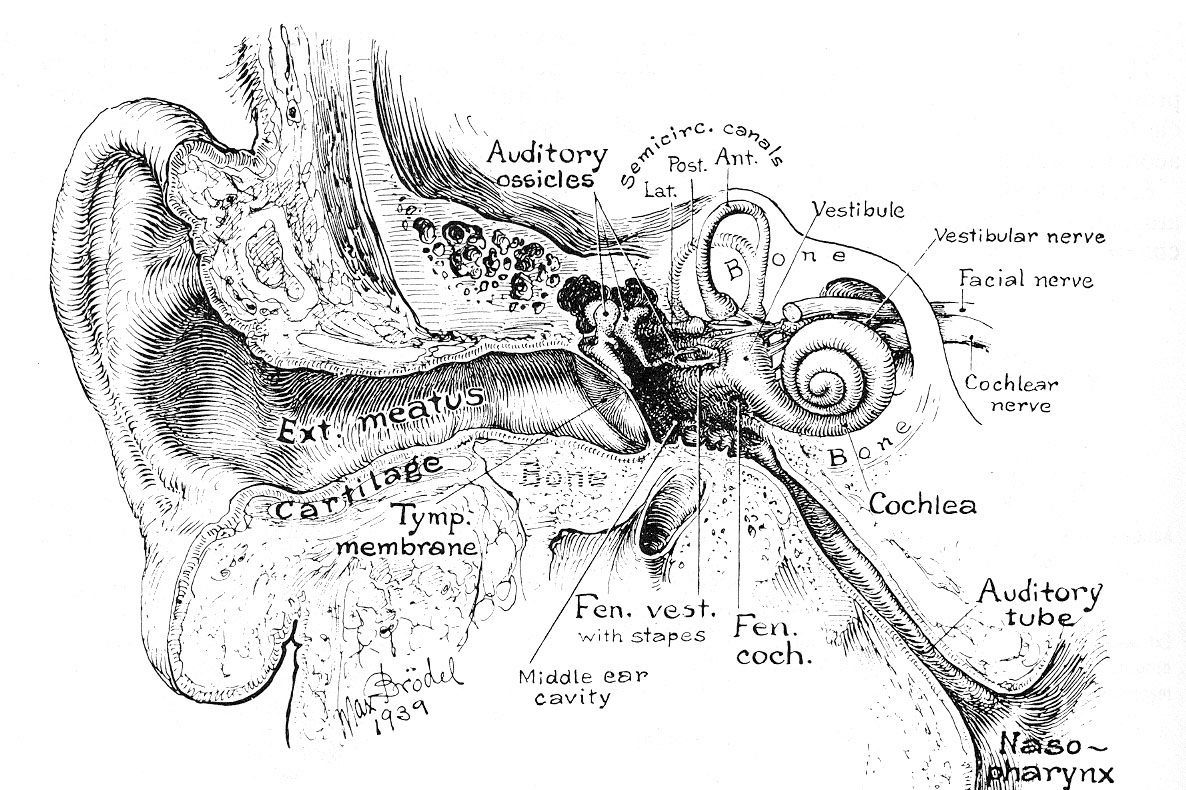

Psychologists Vilayanur S. Ramachandran and Edward Hubbard, in deference to an earlier study by Wolfgang Kohler, showed two shapes to a test group and asked which one they would call a “bouba” and which a “kiki.” One shape had rounded edges and the other had sharp edges with points. Over 95% of the test subjects said that the bouba had round edges and the kiki had sharp edges, suggesting that the participants equate certain sounds with shapes. The phenomenon that connects the sound of a word and its meaning is called phonesthesia or, as the Oxford English Dictionary describes it, “sound symbolism.”

In linguistics, the term phonestheme is used to describe “a phoneme or group of phonemes having recognizable semantic associations, as a result of appearing in a number of words of similar meaning,” e.g. the sl– in sleep and slumber. Even if it’s not about shared letter groupings across words, think of how unpleasant a word like rash is or why many people cringe when they hear moist. Is rash rashlike somehow? Is moist irrevocably dank and unpleasant as wet socks?

*

But don’t forget our curse words, many of which arrive from Anglo-Saxon with heavy—perhaps onomatopoeic—consonants. Like a real adult, I just went and looked up “fuck, v.” in the OED, and here’s one of its earliest written uses (1568) as a intransitive verb: Ay fukkand lyke ane furious Fornicatour. How appropriately severe!*

When I started to try to physically render space in my poems, I started walking more. At the time, I was living in the Oregon Hill neighborhood of Richmond, Virginia, and I had to walk sidewalks undermined by roots and wear. Sometimes the bricks would loosen and move with one’s steps. For me, the best way I was able to combine the description of action with the sound of action was to write, “I walk buckled brick back,” where the b- and k- sounds seemed to me to sound a lot like bricks moving against one another and my shod feed on them.

But that’s all to end with one slippery conclusion: I don’t think there’s any one-to-one equation to achieve a phonesthetic effect in one’s poems, and I likewise think that a heavy ear could easily overdo the effect, after Police Academy’s Larvelle Jones. Still, there’s something to be said—there’s something even romantic—about being able to tell a reader about putting on a tea kettle and having it whistle too.