Reading Elena Poniatowska’s LA NOCHE DE TLATELOLCO Amid The Oaxaca Teacher Protests

In the news this morning a picture flashed on my screen like a scene ripped directly from Elena Poneiatowska’s La Noche de Tlatelolco, a book that I teach from time to time about the ’68 student massacre in Mexico City, in which anywhere from 30-300 (depending on who you believe) students and activists were killed at the hands of Mexican armed forces ahead of the 1968 Olympic games.

Oftentimes, I teach that book as if it were an artifact from another era: this was the political climate and major event surrounding the pueblo movements of ’68. But this picture on my screen was taken in Oaxaca in June of 2016. And the rage of the Mexican pueblo, to this day, is quite literally burning in the streets of Nochixtlan.

In the picture’s foreground, a wiry thin teacher with a rock in his hand; in the background a blurry, disheveled line of granaderos (Mexican riot police) seemingly trying their best to stand uniform to no avail and to no more than five young men, presumably also teachers, from Oaxaca’s radical Section 22 of Mexico’s CNTE teacher’s union who are protesting federal education reform that would bar underperforming teachers from continuing their work in one of the poorest states in Mexico. While the majority of the national CNTE teacher’s union has capitulated to reform, Section 22 (among others) of Mexico’s CNTE see the reform as part of a political ploy to strip politically active dissenters in the region (and within the union) from their posts.

In the photo, the five teachers not only hold their line against the granaderos, but they taunt them.

One granadero hoists his shield into the air as if to deflect a thrown rock, breaking rank with those to his side. With their line is broken, their façade of authority is gone and the teachers know it. And not only do they know it but you can see—in the teachers’ gait, in the slack wristed sling of the foreground’s wind-up-pitch, in the raised hands of the other one dressed in green—that the granaderos know that the teachers know. Their schtick is up.

It should have come as no surprise that Mexican government eventually decided to shoot (as they did in ’68; as they also did in Iguala) if only to maintain—in some sick sense—a modicum of decorum: we are the government; you are the pueblo. But, of course, the shock is still there.

At least 10 known people have died in Nochixtlan. Over 140 people were wounded. And so much of what resonates with me now is the age of many of these protesting teachers—about my age. Just as so much of what resonated with me about the 43 Ayotzinapa students (teachers in training) killed in 2014 were that they were the age of my own students.

As the Grande Dame of Mexican letters, Elena Poniatowska, has asked in her own writing time and time again: what do you make of a state that’s historically made war on its young people? That continues to make war on its educators? That continues to obfuscate the truth surrounding such violence?

For decades, the Mexican public only had Poniatowska’s first-hand accounts in Noche de Tlatelolco to decipher the true events of what happened in the Plaza de Tres Culturas the night of October 2nd, 1968. Today, the facts surrounding the massacre, intentionally sealed by Mexico’s PRI government for nearly 30 years, are largely considered to be part of Mexico’s so-called Dirty War used to suppress intellectual student and populist dissent against the ruling PRI government of the 60’s. And bizarrely enough, now that the ruling PRI is back in power under Peña-Nieto, that same brand of suppression continues in 2016. Which is exactly why Noche de Tlatelolco is more relevant than ever.

Reading the news out of Nochixtlan through the lens of Noche de Tlatelolco, I can’t help but wonder if the power dynamic between the pueblo and the Mexican government has changed all that much.

The parallels between the pueblo of 1968 and the pueblo of 2016 can be seen and read in the imagery of both events: helicopters shooting flares, pluming black smoke, Mexican police shooting live rounds into the bodies of protesters, and, of course, the rift between the Pueblo itself: between those who sympathize with young people but believe, ultimately, that Mexican intellectualism is disruptive to the common peace.

These marked similarities are not to say the two events are equal—they’re not—but there’s something telling about the prevalence and symbology of such imagery in 2016, about the contemporariness of that epoch in Mexican history today which we thought we’d already moved past.

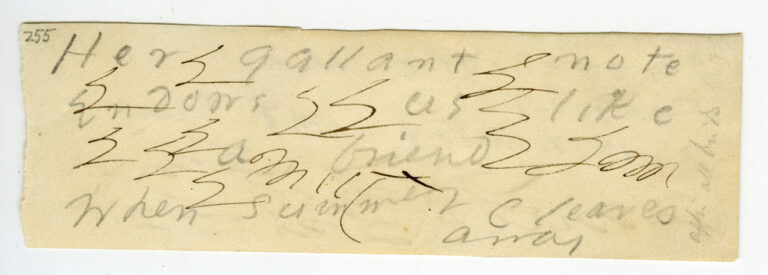

Thinking through Noche de Tlatelolco again, thinking through the images coming from Oaxaca, I’m reminded of a line from the book that I always like to discuss with my students when teaching the text: “Soldado, no dispares; Tú también eres el Pueblo” / “Soldier, don’t shoot. You too are the people.”