Reading in a Brown Body

During my first week of college, at the University of Iowa, several of us students were playing cards in my dorm room, when, unrelated to the game or to the conversation, one of the other freshmen asked me, “What are you?”

During my first week of college, at the University of Iowa, several of us students were playing cards in my dorm room, when, unrelated to the game or to the conversation, one of the other freshmen asked me, “What are you?”

Later, I would learn to expect this question and its innumerable variations. They would be asked of me on a nearly daily basis, coloring all of my experiences and memories of Iowa. That first time, however, I was surprised.

“I’m American,” I said.

“You’re kind of dark for an American,” the other student said.

“No, I’m not,” I said.

Quickly, my surprise wore off. I was asked what I was, where I was really from, where my parents were really from, no, really really from. I was stopped by strangers on the street, in shops, in restaurants, in classes. I was often the only non-white person in the room and I was complemented for my “permanent tan,” and my good English. I was asked if my family ever sat around and talked, the way Iowans do. I became angry. It was 2001, the term “micro aggression” hadn’t yet come into use, and I struggled to describe how isolating it felt to be constantly othered. I was perpetually on guard, aware that soon another person would ask me to explain my skin, my accent, my nationality. How did I come to be brown and American and to speak English?

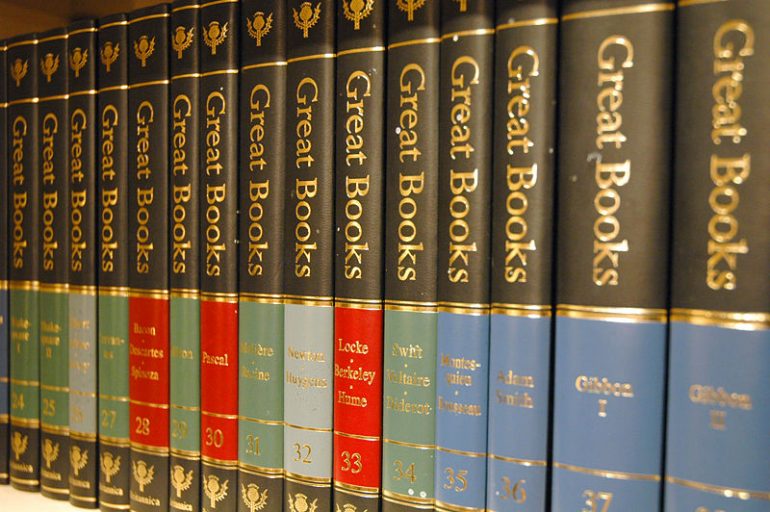

Though I seemed to be foreign to many people in Iowa, they were very familiar to me. By the time I had arrived in Iowa City I had spent most of my life learning the stories of white people, through real-life relationships, as well as through books, film and TV shows. Before I’d ever been outside the southwest, where I am from, I’d already fallen in love with Hemingway, Salinger, Cather, and Twain, and had seen thousands of TV episodes centering on white families and all-white friendship groups. In school I had read classics like The Catcher in the Rye, A Wrinkle in Time, The Outsiders and The Great Gatsby; while books with non-white characters were limited to To Kill a Mockingbird, Huck Finn, and The Bean Trees—all of which still have white authors and white protagonists. I hadn’t had a single non-white literature teacher in high school, and I would not in college. What I’m trying to say is that by the time I was playing cards in my freshman dorm room, I had spent nearly two decades reading, hearing, and watching white lives. I was a kind of expert. But they, like me, had rarely heard, read, or seen the stories of non-white people.

Even though I come from a city with a large Hispanic population, we too were rarely assigned novels or stories by brown authors or with brown main characters. On my own I discovered The House on Mango Street, I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings, and the essays of James Baldwin. Much later, I would seek out the works of Rudolfo Anaya, Ana Castillo, and Luis Alberto Urrea, among many other great non-white writers. I had no idea that finally seeing people like me in fiction would be the whole-making experience that it has become.

But, reading more diverse stories doesn’t just impact the lives of people of color, it affects everyone. Though I am sometimes still angry about my experience in Iowa, I have come to believe that most of the racist questions and comments I was subjected to resulted from naiveté, not malice. Many of my peers in Iowa had no, or very limited, contact with non-white people, and their words resulted from their lack of exposure, not conscious racism. Not only could they not draw upon real-life relationships with brown people, but the homogeneity of the literary cannon and popular culture had failed them, too. We all need more diverse books, not just people from underrepresented groups. “Diverse” isn’t an abstract idea, a quota system, or a moral high ground; it’s the real world that we all live in right now. Our stories should strive to represent it.