Reading the Signs: Letter from Prague

For the past six months, I’ve been living in Prague—a small but fierce city in Central Europe where despite the cumulative oppressions of Nazi occupation and decades of isolation and communist rule, residents still maintain a well-developed sense of irony. Monitoring the (Anglophone) news from the self-exile of Prague imbues the headlines, it seems, with more gravity. The white nativist turns of Brexit, Trump, and the run up to the French election; the completely documented, viewable, and preventable slaughter unfolding in Aleppo; avowed Russian tampering in the U.S. election; Trump’s reprisals against protestors and the press; the GOP’s unconstitutional power grab in North Carolina, the state that I’ve come to call home, are tinged with hard-to-believe totalitarian encroachment. Is this what the Munich Agreement (affectionately dubbed the “Munich Betrayal” here) felt like for Czechoslovakia when European powers ceded the Sudetenland to Adolf Hitler? Was it similarly hard to wrap your mind around the purging of non-Communist ministers from government in the days before the Soviet-backed Communist coup? Is this what the course to out-and-out fascism feels like? The city reads like a parable.

One of the more moving experiences of my brief ex-patriotism was watching the film Anthropoid (2016) in a cinema on Biskupcova Street. The film tells the story of the successful Czechoslovak Resistance operation by the same name in which two paratroopers—Jozef Gabčik and Jan Kubiš—carry out the assassination of the third highest ranking officer of the Nazi party and the architect of the Final Solution, Reinhard Heydrich. For his harsh rule of the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, Heydrich was known as “The Butcher of Prague.” I recommend the film, but note that viewing (despite dreamy and mercurial Cillian Murphy playing Gabčik) is a brutal experience. Devoid of soundtrack, slow and monotonous at times, with shows of historically accurate but barbaric violence, the film is meticulous to the point of cruelty.

Perhaps it is this slow time which is the most loathsome part of a totalitarian offensive. While it seems like everyone is talking about George Orwell’s 1984 (1949) these days, I’ve been thinking of his Homage to Catalonia (1938). This memoir chronicles Orwell’s time fighting the Fascists for the Worker’s Party in the Spanish Civil War. The slim volume unfolds with fastidious, often boring, detail of wartime tedium. Orwell describes this as, “violent inertia, a nightmare of noise without movement.” He narrates the process of bathing and laundering loused clothes in the battle trenches, pays special attention to the constant scramble for the luxury of cigarettes, untangles the gnarled web of anti-Fascist factions vying for power and battleground, tells of his odd urges to graffiti walls with scrawls of political propaganda when he’s supposed to be in hiding. The account is not a valorization of resistance, but rather a portrait of Orwell’s own exasperation. He and his comrades, ordinary men and women he emphasizes, become crestfallen and, eventually, Franco rises to power anyway.

The essay, “Winter in the Abruzzi” (1944) by Italian writer, Natalia Ginzburg has this same stagnant quality. In the early years of the war, Ginzburg and her husband abandon Rome for the countryside, hoping that they and their children can avoid the reprisals against notably Anti-Fascist intellectuals. I’ve long admired Ginzburg for the social and political implications she can imbue in an old pair of shoes or the quiet, unshowy intimacy between lovers. This essay is no different. She writes of the twist of seasons from “parched” summer to the “slow sadness” of a winter that mirrors her own exile. She reports parochial goings-on: visits to the hearths and homes of Vincenzina da Secondina, the school caretaker’s catty dustup with a neighbor, the heralded birth of a second set of twins to Gigetto di Calcedonio, and the church bells ringing every evening at five. There is the tromp of long walks in the snow, her children’s excitement when oranges are delivered to the shop across the way, and the knell of fairy tale rhymes being sung by Crocetta, the cleaning woman. When winter finally thaws, you believe that Ginzburg’s exile will too. After all, departures presume a return.

But Ginzburg’s isolation just changes shape. “My husband died in Rome, in the prison of Regina Coeli, a few months after we left the Abruzzi,” she writes matter-of-factly at the essay’s close, saying little of her husband’s capture in a clandestine print shop and severe torture by the Italian police under Mussolini. These specifics are so common as to be rote, it is the monotony of Abruzzi that becomes the distinguishing feature. “Faced with the horror of his solitary death, and faced with the anguish that preceded his death, I ask myself if this happened to us—,” she continues, “to us, who bought oranges at Giro’s and went for walks in the snow. I had faith then in a simple, happy future, rich with fulfilled desires, with shared experiences and ventures. But that was the best time of my life, and only now, now that it’s gone forever, do I know it.”

Reprisals for Operation Anthropoid in the Czech Republic were swift and savage. Hitler and Heinrich Himmler identified a town called Lidice about a half an hour outside of Prague. To “make up for [Heydrich’s] death,” they summarily executed all the men over age 15 in the village, sent most women and children to a concentration camp where they were gassed, and identified a few “racially suitable” children to be Germanized. Few returned to their hometown after the war. Those that did found that the Nazis burned the entire village, slaughtered all the animals, rerouted the river that flowed through the center of town, and dug up and destroyed the village cemetery. Two weeks later, upon finding a radio transmitter, they repeated this process, more or less, in the village of Ležaky. Back in Prague, after a member of the Resistance betrayed his compatriots, the Getstapo rounded up all of those men, women, and children who had aided Gabčik and Kubiš by housing them, feeding them, passing messages, storing equipment, or simply being associated with those that abetted the men. Each was excuted, from the youngest child to the oldest grandmother. Estimates place the number of people murdered in retaliation to Operation Anthropoid somewhere around 1300.

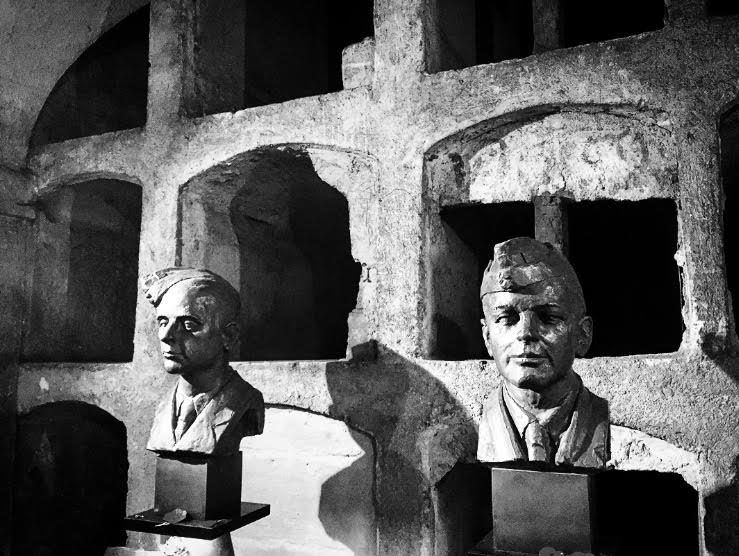

The assassins along with five other paratroopers of the Czechslovak Resistance hid for several dull weeks in the crypt of the Cathedral of the Saints Cyril and Methodius, just a short walk from my apartment. When they were found, after a two-hour gun fight with 750 SS Soldiers, these seven men were either killed or committed suicide. Today, there’s a small museum in the crypt with bronze busts of each of these men and a short biography on a placard beneath—one was a confectioner, one a tanner who worked for the shoe company, and another, I read, had been trained to operate a boiler.

There are no equivalencies between these histories and our current moment. Each has specific time and circumstance, distinct places and persons to distinguish their critical moments. But, there is something about a mood, a listlessness, an exasperation, that seems to be increasingly familiar. As I end the calendar year in Prague, it becomes harder and harder not to read all of the signs.