Review: PRODIGALS by Greg Jackson

Prodigals

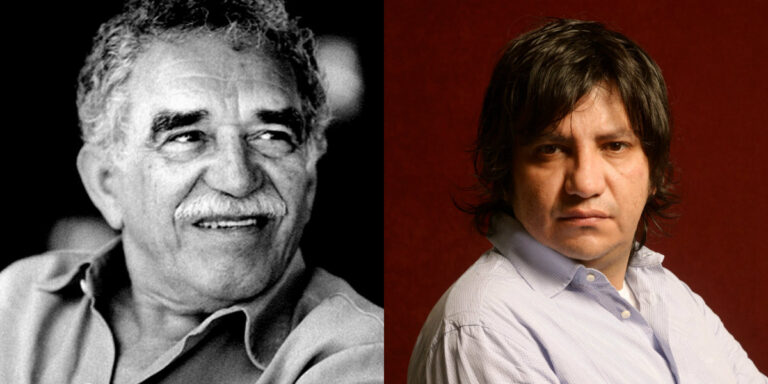

Greg Jackson

Farrar, Straus and Giroux, Feb 2016

240 pp; $25

Reviewed by Eric Farwell

Consisting of eight short stories that focus on the inner lives and small experiences of (mostly) white thirty-somethings, Greg Jackson’s debut collection, Prodigals, is one that stands out for its mental acuity and philosophical athleticism. A former fellow of the MacDowell Colony, Jackson puts his gifts on full display here. No minute human experience is too small to unpack with high diction and zeal, for pages, until it gives way to revelation, and ultimately, the humanity resting at the core of these stories’ protagonists.

When reading, it’s easy to make comparisons between Jackson and David Foster Wallace or F. Scott Fitzgerald—writers who are generous with their interior world-building and can spend pages upon pages describing the journey of one particular feeling as it needles its way into something resembling transcendence. However, those comparisons are a bit short-sighted, as Jackson, unlike DFW or F. Scott, seems to be genuinely investigating life as someone in between the stations of youth and middle age via his characters.

Jackson goes about these investigations with a prose style that is equal parts ivory tower intellectualism and genuine pathos. Sentences read as a potent mix of the breathtaking and unsure, questioning as much they answer any question they’re hoping to navigate. Take this sentence, for example, from “Amy’s Conversion”:

What I see now is the twilit lake, soot clouds in the distance, sky that faint humid orange blur it could be some summer nights, a burning calico, heat rising from the water like the ghost life within it.

“Amy’s Conversion” focuses on Amy and Jessie, two young women who leave the church they grew up in to become an anarchist and an office manager, respectively. Jessie, the protagonist, has been sexually obsessed with Amy since their teen years, and in many ways the story is every bit as much about her moving past that as it is reconciling past idealism with their current lives. Jessie struggles in her romantic life because she can’t let go of a fantasy of Amy that never existed, and Amy flits about life searching for the promises religion never quite provided for her. Neither character knows how to solve these borderline-existential crises, but the searching and fumbling is where Jackson is most comfortable, as he searches along with his creations. In some ways, the characters that populate Jackson’s stories are haunted, but what exactly haunts them is difficult to pin down.

This haunting doesn’t always resolve by each story’s end, but rather seems to bleed into the lives of each set of characters, lingering in the background as other issues are dealt with. One issue that seems to preoccupy Jackson is white privilege, and how entitlement is dialed up or toned down as we burn through our twenties. The characters he deals with are relatively similar, with each living partially in the fog of their upward-mobility, unable to come out fully unscathed from life’s setbacks. In “Epithalamium,” Hara, a recently divorced attorney tries to comprehend what went wrong. She mopes about her beach house, oblivious to both how alone she truly is, as well as how much she isolates herself when utilizing her upper-tier snobbishness, which she wears like a mask. Jackson gently eases us into Hara’s process of ruminating and growth, writing:

Hara would retrieve a bottle of Zeke’s expensive wine from the cellar and scatter the family photos she kept in shoeboxes on the living room rug. It was not clear to her if a clean line could be drawn from the hipshot young girl in a bathing suit on the beach in Goa to the self-pitying wretch she saw gazing back at her in the glass of the French doors.

Here, Hara, like many of Jackson’s lost souls, is searching for explanations where none likely exist.

At other times, the privilege of these characters serves as a door one can lock and hide behind. In these instances, the stories take on an aesthetic quality that wouldn’t be out of place in an Updike novel. In “Wagner in the Desert” and “Dynamics in the Storm,” position is used as a barricade from emotional growth, allowing those using it to marinate in their stagnation. Interestingly, the protagonist of “Wagner in the Desert” has his isolation disrupted by a passive character, while the therapist in “Dynamics in the Storm” is confronted directly by her patient, as she’s trapped in a car with him as they try to find shelter from storms both literal and internal. In each piece, the narrative is driven by strength of ego, giving way to real disruption when a character with the right personality to obsess or get close slides into the protagonist’s life like a knife to the ribcage. Here, Jackson seems to be hinting that what we need in order to move forward rarely seems apparent at first blush.

Greg Jackson’s debut collection is full of different voices that seem to make up a collective sound. These stories take their characters to task as much as they sympathize or identify with them. Jackson may well be trying to figure out the answers to life his characters so desperately need. If his collection is about anything, it’s about the possibility that each of us can avoid falling into the great sea of the unknown, and opt instead to rise, recognize, and sing.

Eric Farwell is currently an adjunct professor of English at both Monmouth University and Brookdale Community College in New Jersey. His writing has appeared in places like PAPER digital, The Rumpus, Electric Literature, Pleiades online, Spillway (forthcoming), and The Writer’s Chronicle (forthcoming). He is currently developing work on the correlation between George Saunders and Jean Baudrillard.