Revisiting Alice Munro’s “Material”

For a long time I didn’t like reading—or writing—stories about writers. There seemed to be something self-congratulatory and navel-gazing about it. But recently I’ve found myself drawn to fiction that’s about writers: Lisa Halliday’s Asymmetry, Sigrid Nunez’s The Friend, Rachel Cusk’s Outline, Jenny Offill’s Department of Speculation. My interest, I’m sure, comes in part from being enrolled in a writing program, an environment that often stokes the impulse to both navel-gaze and develop curiosity about the lives of other writers. But books about writers also directly address certain questions that other novels might only deal with obliquely: what are stories made of? Why do we tell them, and who tells them? How must life be transformed in order to become literature? The books I’ve mentioned are written by women. Some of them center on women writers and their interactions with literary men, which raises other, related questions. When women write about writers, how does their work riff on the tropes of the fictional male writer (as written by men)? How does their work engage with societal pressures on and expectations for women, especially women who move through literary circles?

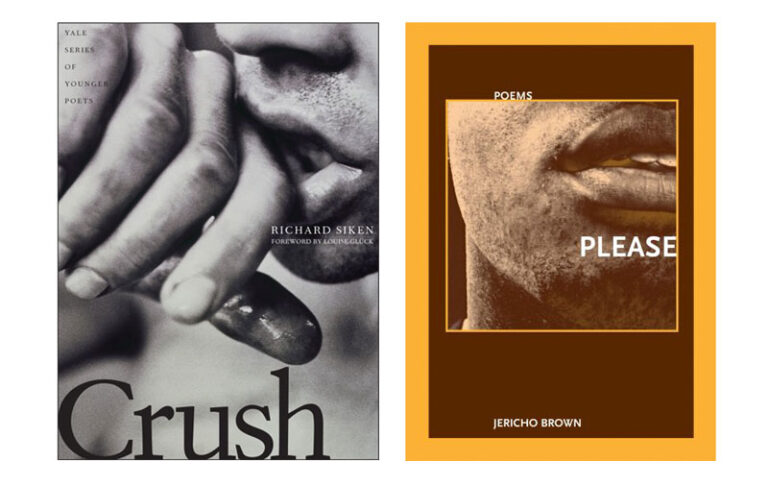

A favorite short story of mine masterfully explores many of these questions. Alice Munro’s “Material,” included in her 1974 collection Something I’ve Been Meaning to Tell You, is narrated by an ex-wife of an archetypal Famous Male Writer named Hugo. The anger of the narrator is palpable as she relates the story of their marriage, its fragmentation, and her life afterwards. But the story isn’t really about their relationship, or even about the woman who narrates the story; rather, it’s concerned with the business of constructing stories from “real life.”

The narrator remembers, in great detail, a neighbor she and Hugo had when they were living together. The neighbor, Dotty, had had a colorful life: she was a sickly woman who’d been married twice and was now having sex for money in her basement apartment. The narrator is immediately fascinated by her; Hugo, not so much. Over a decade later, the narrator comes across a collection of stories by Hugo, and one of the stories is about Dotty. In the story she’s been “lifted out of life and held in light, suspended in the marvelous clear jelly that Hugo has spent all his life learning how to make.” “Material” explores the process by which life becomes art, and also raises the question of the ideal balance between ego and observation in a writer. The story positions Hugo as inward-looking, nervous, gathering his material and energy from a “source” that’s indecipherable to the narrator. The narrator isn’t a writer, but can be read as a woman who under different circumstances might have been (the story ends with her, pen in hand, preparing to write an angry letter to Hugo about the story, and a confession: “I do blame them. I envy and despise.”). She’s outward looking, out of boredom and necessity, and she gathers the material—particularly about Dotty—that Hugo dismisses.

From the first page Munro introduces the tension between life and literature—and specifically between a certain kind of domestic life and a certain kind of literary figure. The narrator, who occasionally sees advertisements for her ex-husband’s readings and events, thinks:

[W]ill people really go, will people who could be swimming or drinking or going for a walk really takes themselves out to the campus to find the room and sit in rows listening to those vain quarrelsome men? Bloated, opinionated, untidy men, that is how I see them, cosseted by the academic life, the literary life, by women.

What I love about Munro’s portrayal of Hugo in the story is her ability to unmask him—to take him down from his pedestal, to make him look human, and occasionally ridiculous, to the reader—while at the same time validating, in some ways, the work that he does and the questions that he, as a writer, wrestles with. The narrator is initially scathing about Hugo: “Girls, and women too, fall in love with such men, they imagine there is power in them.” She pokes holes in the author bio on his book, which characterizes him as someone who’s “worked as a lumberjack, beer-slinger, counterman, telephone lineman and sawmill foreman, and has been sporadically affiliated with various academic communities.” The narrator clarifies: “He had a job painting telephone poles. He quit that job in the middle of the second week because the heat and the climbing made him sick . . . Hugo found a job marking Grade Twelve examination papers. Why didn’t he put that down? Examination marker.”

Hugo’s self-mythologizing is a theme throughout the story. Munro raises questions about the relationship between two things that often coincide in writers: the first is a certain amount of self-indulgence and self-mythologizing; the second is the difficult work of putting aside the ego and observing the world. Historically, women—wives of writers particularly—have had to take on the role of standing between their artist husbands and the “real world.” As Munro’s narrator notes of the literary events she sees advertised, “The wives of the men on the platform are not in that audience. They are buying groceries or cleaning up messes or having a drink.” The “vain quarrelsome men” are insulated from the world; the women, meanwhile, are constantly in the world, gathering material.

This paradox is at the heart of the story, and at the root of the narrator’s anger: that although she’s the one who befriends Dotty, and observes her, and takes an interest in her, it’s Hugo who has the time to abscond from the world and shape Dotty into fiction. It’s also Hugo who has the permission to “ignore or use things.” In other words, the narrator and Hugo can be read as two different object lessons: one about excess of self-indulgence (Hugo), and the other, the dearth of it (the narrator). In “Material” Munro implicitly asks, what’s the balance between collecting “material” and withdrawing from the world in order to shape it? Of course, she doesn’t answer this question. But “Material” is a story that always gives me hope that writing about writers can be complex and nuanced. It’s a story about the different ways people respond to the world based on their circumstances; it’s about which groups are empowered to live and work with “authority,” and who are not expected to be “at the mercy,” as the narrator implies that she herself is. And, as in all writing about writers, there’s something simple and pleasurable about the artifice of fiction stripped away, about letting the reader see a so-called Great Writer as mundane and silly. Maybe, in fact, that’s why writers in particular should read about writers: to be taken down a notch, and to remember, as Munro suggests, that their first duty is to their material.